Category:Early Islamic Studies

The connections between formative Islam and late antique Judaism and Christianity have long deserved the attention of scholars of Islamic origins. Since the 19th century Muhammad’s early Christian background, on the one hand, his complex attitude – and that of his immediate followers – towards both Jews and Christians, on the other hand, and finally the presence of Jewish and Christian religious motifs in the Quranic text and in the Hadith corpus have been widely studied in the West. Yet from the 1970s onwards, a seemingly major shift has taken place in the study of Islam's origins. Whereas the grand narratives of Islamic origins traditionally contained in the earliest Muslim writings have been usually taken to describe with some accuracy the hypothetical emergence of Islam in mid-7th-century Arabia, they are nowadays increasingly regarded as too late and ideologically biased – in short, as too eulogical – to provide a reliable picture of Islamic origins. Accordingly, new timeframes going from the late 7th to the mid-8th century (i.e. from the Marwanids to the Abbasids) and alternative Syro-Palestinian and Mesopotamian spatial locations are currently being explored. On the other hand a renewed attention is also being paid to the once very plausible pre-canonical redactional and editorial stages of the Qur'an, a book whose core many contemporary scholars agree to be a kind of “palimpsest” originally formed by different, independent writings in which encrypted passages from the OT Pseudepigrapha, the NT Apocrypha and other writings of Jewish, Christian and Manichaean provenance may be found, and whose liturgical and/or homiletical function contrasts, notwithstanding the number of juridical verses contained in the Quranic text, with the overall juridical purposes set forth and projected onto it by the later established Muslim tradition. Likewise the earliest Islamic community is presently regarded by many scholars as a somewhat undetermined monotheistic group that evolved from an original Jewish-Christian milieu into a distinct Muslim group perhaps much later than commonly assumed and in a rather unclear way, either within or tolerated by the new Arab polity in the Fertile Crescent or outside and initially opposed to it; or else as being originally a Christian movement. Finally the biography of Muhammad, the founding figure of Islam, has also been challenged in recent times due to the paucity and, once more, the late date and the apparently literary nature of the earliest biographical accounts at our disposal. In sum three major trends of thought define today the field of early Islamic studies: (a) the traditional Islamic view, which many non-Muslim scholars still uphold as well; (b) a number of revisionist views which have contributed to reshape afresh the contents, boundaries and themes of the field itself by reframing the methodological and hermeneutical categories required in the academic study of Islamic origins; and (c) several still conservative but at the same time more cautious views that stand half way between the traditional point of view and the revisionist views. Surveying the history of these three different approaches to the manner in which Islam emerged, the role played by Muhammad and the nature of the Qur'an should provide a comprehensive overview of the significance of this particular field of research for late-antique religious studies, both Jewish and Christian.

Early modern Islamic studies and the traditional approach to the origins of Islam

The founding in Paris in 1795 of the École Spéciale des Langues Orientales Vivantes marks off the beginnings of modern Islamic studies, for it was under the school's second director, Antoine Isaac Silvestre de Sacy, that the first systematic curriculum for the teaching of Islamic languages, culture and civilisation was established in Europe. Yet the modern study of the Qur'an began with Gustav Flügel (1802-1870), Gustav Weil (1808-1889) and Theodor Nöldeke (1836-1930) in Germany. Flügel published the first modern edition of the Qur'an in 1834 (which was largely used before the Royal Cairo edition of 1923) and a Concordance to its Arabic text in 1842 (although it is difficult to know which precise manuscripts he relied on), whereas both Weil and Nöldeke published in 1844 and 1860, respectively, two historical-critical introductions to the Quranic textus receptus of which Weil's knew a second edition in 1878 and Nöldeke's, initially published in Latin in 1856 and later completed by Friedrich Schwally (in 1909 and 1919) and Gotthelf Bergsträsser and Otto Pretzl (in 1938), soon became the seminal and most authoritative work in the field, gaining wide, even uncontested reputation until the present day. As to Muhammad, the first modern studies were those published by Abraham Geiger (1810-1878) in 1833, Gustav Weil in 1843, Aloys Sprenger (1813-1893) between 1861 and 1865, William Muir (1819-1905) between 1858 and 1861, and again Nöldeke in 1863. Geiger's pioneering essay on Muhammad's life and Weil's study on the Biblical legends known to the early Muslims (1845) were also the first works to explore a number of possible early Islamic borrowings from Judaism, whilst its apparent Christian influences (on which a few authors like Ignaz Goldziher and Henry Preserved Smith already had provided some useful insights in the second half of the 19th century) were first systematically explored by Carl Heinrich Becker in 1907. But modern scholarship on Islam's origins is indebted too to the groundbreaking works of Ignaz Goldziher (1850-1921), whose Muhammedanische Studien, published in 2 vols. between 1889 and 1890, represented a first, successful and in many ways still valid attempt to thoroughly examine the making and early development of Islamic identity, and its literature, against their complex historical and religious setting.

For the most part, however, and notwithstanding their intrinsic value, these early studies (save those of Geiger and especially Goldziher, which were little conventional in both their approach and conclusions) tended to adopt and either explicitly or implicitly subscribe, and thus validate, the grand narrative of Islam's origins provided in the early Islamic sources. This is particularly noticeable in Nöldeke's case, whose chronology of the Qur'an largely follows the traditional Muslim chronology, and whose approach to the Quranic text as a single-authored unitary document is nowadays considered too naïve, and accordingly regarded as outdated, by an increasing number of scholars. After all Nöldeke had studied with, and was the most salient disciple of, Heinrich Ewald (1803-1875), a German conservative theologian and orientalist who opposed the new critical methods essayed by Ferdinand Christian Baur and the Tübingen School in the neighbouring field of early Christian studies. In Ewald's view, all a scholar of early Islam was expected to do was to learn as much Arabic as possible and willingly accept the traditional account of the rise of Islam provided in the early Islamic sources, which veracity, therefore, ought not to be questioned. Supported by Nöldeke and his followers, this view rapidly became mainstream and has been prevalent in the field with only very few exceptions ever since.

Other likewise prominent works published in the late 19th century and the first half of the 20th century (up to the late 1950s) include those of Hartwig Hirschfeld (1878, 1886, 1902), William Muir (1878), Charles Cutler Torrey (1892), William St Clair Tindall (1905), Leone Caetani (1905-1926), Israel Schapiro (1907), Paul Casanova (1911-1924), Lazarus Goldschmidt (1916), Goldziher (1920), Wilhelm Rudolph (1922), Josef Horovitz (1936), Heinrich Speyer (1931), David Sidersky (1933), Anton Spitaler (1935), Richard Bell (1937-1939), Arthur Jeffery (1937, 1938), Régis Blachère (1947, 1949-1950), and Thomas J. O'Saughnessy (1948) on the Qur'an; Karl Vollers (1906) and Alphonse Mingana (1933-1939) on ancient Arabic language and manuscripts; David Samuel Margoliouth (1905, 1914), Arent Jan Wensinck (1908, 1932), Caetani (1910), Henri Lammens (1912, 1914, 1924), Bell (1926), Tor Andrae (1926, 1932), Blachère (1952), and William Montgomery Watt (1953, 1956) on Muhammad, the early History of Islam and the early Muslim dogma; Alfred Guillaume (1924) and Wensinck (1927) on the early Islamic traditions; Joseph Schacht (1950) on the making of Islamic law; and Samuel Marinus Zwemer (1012), Wilhelm Rudolph (1922), Margoliouth (1924), Heinrich Speyer (1931), Torrey (1933), Haim Zeev (Joachim Wilhelm) Hirschberg (1939), Abraham I. Katsch (1954), Solomon D. Goiten (1955), and Denise Masson (1958) on early Jewish-Christian-Muslim relations. Amongst the major arguments, discussions and controversies put forward in this period the interpretation of emergent Islam as an heretical offshoot of Christianity (Lammens), the textual discrepancies between the old codices of the Qur'an and its foreign vocabulary (Jeffery), and the representation of Muhammad as either a statesman (Watt) or an apocalyptic prophet (Casanova) deserve a special mention.

Later developments and the rise of a critical approach to the Qur'an and the early Islamic sources

Growing attention was paid in the second half of the 20th century to the situation of the Arabian Peninsula on the eve of Islam as depicted in the early Islamic sources and the archaeological witnesses available to us; the information supposedly gather together by the early Muslim authors regarding the rise of Islam and the different types of literature that they produced; the biography of Muhammad and his polemics against both Jews and Christians; the language, structure, contents, message and apparent Jewish and Christian subtexts of the Qur'an, as well as its competing interpretative traditions; the formation of the Islamic state and the clash between different Muslim groups in the first centuries of Islamic rule; and both the non-Muslim views of Islam and the relationship between Jews, Christians and Muslims in the first Islamic centuries. Especially noteworthy were the works by François Déroche and Sergio Noja (1998) on the early Quranic manuscripts; Günter Lüling (1974), Richard Burton (1977), John Wansbrough (1977), Neal Robinson (1996), Stefan Wild (1996), and Andrew Rippin (1999) on the Quranic corpus, its collection, function, style, contents and presumably encrypted texts; Cornelis H. M. Versteegh (1993) on Arabic grammar and early Qur'anic exegesis; Andrew Rippin (1988), Claude Gilliot (1990), and Marjo Buitelaar and Harald Motzki (1993) on Quranic exegesis; Toshihiko Izutsu (1959) on Quranic semantics; Helmut Gätjie (1971), Fazlur Rahman (1980), O'Shaughnessy (1985), Jacques Berque (1993) on the teachings of the Qur'an (1985); Jacques Jomier (1959, 1996), Heikki Räisänen (1972) and Roberto Tottoli (1999) on the analogies and differences between several themes in the Bible and the Qur'an; Youakim Moubarac (1998) and Reuven Firestone (1990) on the evolution of the Abraham-Ishmael legends in early Islam; David Thomas (1992), Steven M. Wasserstrom (1995), Camila Adang (1996), Michael Lecker (1998) and Uri Rubin (1999) on early Jewish-Christian-Muslim relations; Räisänen (1971) and Jane Dammen McAuliffe (1991) on the Quranic image of Jesus and Christianity; Maxime Rodinson (1961), Watt (1961), Roger Arnaldez (1970), Noja (1974), Michael Cook (1983), Martin Lings (1983), Gordon E. Newby (1989), Francis E. Peters (1994), Rubin (1995), Marco Schöller (1996, 1998) and David Marshall (1999) on Muhammad and his early biographies; Meir J. Kister (1990), and Shmuel Ahituv and Eliezer B. Oren (1998) on pre-Islamic Arabia and the rise of Islam; Schacht (1964), Albrecht Noth (1973), Wansbrough (1978), Gautier H. A. Juynboll (1983, 1996), Motzki (1991) and Fred M. Donner (1998) on the early Islamic traditions and literature; Watt (1973), Cook (1981) and Mohammad Ali Amir-Moezzi (1994) on the formative period of Islamic thought and early Islamic sectarianism; Peter Brown (1970), Patricia Crone (with both Cook and Martin Hinds, 1977, 1980, 1986, 1987), Donner (1981), Suliman Bashear (1984), Gerald R. Hawting (1986, 1999), Hamid Dabashi (1989), Garth Fowden (1990), Wilferd Madelung (1997), and Firestone (1999) on the rise of Islam and early Islamic history; and Bashear (1997) and Robert G. Hoyland (1997) on the early non-Muslim views of Islam.

A number of these studies (e.g. those of Schacht, Lüling, Wansbrough, Crone, Cook, Bashear, Hawting, Rippin and Rubin) adopted, nonetheless, a highly critical view towards the "data" transmitted in the early Islamic sources concerning the economy and politics of 7th-century Arabia, the rise and early development of Islam, the alleged biography of Muhammad and the elaboration, collection and later canonisation of the Qur'an. Drawing partly on Goldziher, Schacht questioned the historicity of the Hadith collections. Lüling attempted at reconstructing the textual materials latter reworked into the Qur'an and suggested that they were but Christian liturgical texts. Wansbrough analysed both the Qur'an and the earliest Islamic writings about the rise of Islam with the tools of Biblical criticism and concluded that if the former is to be regarded as a collection of originally independent texts later unified by means of certain rhetorical conventions on whose origin and function we know almost nothing, the earliest Islamic sources should likewise be envisaged as elaborated literary reports that tell us more about their authors' concerns than about how things really took place – a point shared by Rubin in spite of his more traditional curriculum. For their part, Crone and Cook submitted to criticism the way in which such purely literary sources re-presented the rise of Islam and its historical and geographic background by reviewing the non-Muslim documents contemporary to the emergence and early expansion of Islam, in addition to which they also studied the plausibly limited role played by the Arabian Peninsula along the trade routes of the late-antique Near East, which led them to cast doubts on the apparent causes that converged to make possible the rise of Islam. Bashear too rejected the traditional account of Islam's origins and essayed a new interpretation according to which Islam gradually arose from within a Jewish-Christian context – a thesis that was independently developed by Hawting, a pupil of Wansbrough who later focused his research on the first centuries of Islamic rule. Whereas another of Wansbrough's disciples, Rippin, undertook the task of scrutinising the beginnings of Quranic exegesis.

Between tradition and change

Used to look at things through the lens of the Muslim tradition, many scholars were not convinced by these revolutionary approaches, which they judged excessively controversial and have often been passionately dismissed rather than theoretically discussed. Yet a number of such scholars felt compelled to at least embrace the innovative and rich terminology displayed in those audacious studies, or else realised that, notwithstanding their hypercritical results, some of the new methodologies displayed in them could be profitable in some measure and contribute to renew the field of early Islamic studies. This twofold attitude has made possible, moreover, the appearance of the still conservative but somewhat more cautious view currently shared, though differently approached and developed, by a growing number of early Islamic scholars, who generally claim that even though the early written sources of Islam may very well date to a later period, they are reliable enough and offer us a fair picture of the events they comment upon or describe, and that the contradictions inherent in them do not preclude the veracity of the master narrative displayed by their authors, which therefore should remain unchallenged. The aforementioned works by Motzki and Donner illustrate well enough this appeasing approach, which Angelika Neuwirth, Michael Marx and Nicolai Sinai have recently endorsed in their Quranic studies, as well. But judging from their supporters' overall conventional, and occasionally biased insights and assertions ("prioritising intertextuality analytically and interpretatively decontextualises Quranic emergence and extrudes history from the picture, . . . [thus] lend[ing] credence to the situation wonderfully described by Paul Valéry as he spoke of 'an Orient of the mind': 'a state between waking and dreaming where there is no logic nor chronology to keep the elements of our memory from attracting each other in their natural combination,'" writes Aziz al-Azmeh, as though we could a priori fancy a reliable historical context that would otherwise be at risk of vanishing, when unfortunately the only one we have from the outset is the literary one fabricated by the Muslim tradition, for which reason prioritising intertextuality on the basis of the undeniable Quranic verbatim reuse and ad hoc modification of a series of earlier Jewish and Christian texts would seemingly just help to [re-]contextualise its redactional process and welcome history, for once, in the picture instead of keep clinging to a state more close to dreaming than waking where both logic and chronology are sacrificed at the altar of a fabricated memory and hence re-shaped in an unnatural combination) it is difficult to tell whether this moderate and at times apparently sophisticated view truly offers a fresh look into the origins of Islam or merely serves to disguise the same old ideas advocated by earlier, more conservative scholars. Still, it is the view that has gained widest acceptance in the field in the past decade.

Recent studies in the field

More or less sensitive to this paradigm shift - if the term is not too ambitious – i.e. oscillating between its partial acceptance and its refusal (with a number of earlier revisionist scholars having recently endorsed a more conventional position, as is the case of both Crone and Cook) amongst the major works published in the last fifteen years the following books should be mentioned: McAullife’s encyclopaedia of the Qur'an (2001), as well as Cook’s introduction (2001) and McAuliffe’s and Rippin’s companions to the latter (2006), Isa J. Boullata’s and Daniel A. Madigan’s volumes on the religious language of the Qur'an and the Quranic self-image (2000 and 2001, respectively), Déroche’s on its written transmission in early Islam (2009), Neuwirth, Marx and Sinai’s on the Quranic milieu (2011), Rippin’s new explorations of Quranic exegesis (2001), Tottoli’s and on the Bible and the Qur'an (2000) Reeves’ volume on Quranic and Biblical intertextuality (2003), Amir-Moezzi’s dictionary of the Qur'an (2007), Emran El-Badawi's study on the Qur'an and the Aramaic Gospel traditions (2014), Norman Calder, Jawid Mojaddedi and Rippin’s sourcebook of early Muslim literature (2002), Jonathan E. Brockopp’s companion to Muhammad (2010), Irving M. Zeitlin’s study on the historical Muhammad (2007), Motzki’s volume on the biography of Muhammad and its sources (2000), Donner’s and Aziz al-Azmeh's monographs on the origins of Islam (2010 and 2014, respectively), Crone's essay on the establishment of the Islamic empire (2010), Cook’s and Hawting’s studies on the origins of Muslim culture and tradition and the development of Islamic ritual (2004), Chase F. Robinson’s essays on Islamic historiography (2003), the Muslim conquest of northern Mesopotamia (2004) and the formation of the Islamic state under ‘Abd al-Malik’s rule (2005), Andrew Marsham’s on the early Islamic monarchy (2008), Najam Haider’s, Maria Massi Dakake's and William F. Tucker’s essays on early Shiite identity (2007, 2008 and 2011, respectively), Milka Levy-Rubin’s study on non-Muslims in early Islam (2011), Michael Bonner’s on the early Arab-Byzantine relations (2004), David Thomas’s volume on the relations between Syriac Christianity and early Islam (2001) and Barbara Roggema’s study on Syriac apocalyptic responses to the rise of Islam (2009), Emmanouela Grypeou, Mark Swanson and Thomas’s volumes on the encounter of eastern Christianity with early Islam (2006, 2013), Sidney H. Griffith's study on the cultural and intellectual life of the Christians living under early Islamic rule (2012), Fowden's recent essay on the relationship between Graeco-Roman, Syrian Christian, Jewish, Arab, Iranian and early Islamic cultures in late antiquity, and Jonathan P. Berkey’s comprehensive handbook of Islamic history (2003).

Revisionists views and their challenges

At the same time, and considering that the entire narrative of Islamic origins is worth being revised and deserves being retold, a remarkable number of senior and young scholars alike have fully assumed the need to look at things from a totally new perspective and have contributed with their insights to further develop different revisionist views by exploring afresh - albeit with not equally convincing results, but this is just normal in any academic discipline – issues such as the relationship between method and theory in the study of Islamic origins (Herbert Berg, 2003) sectarian milieu out of which Islam emerged (Edouard Marie Gallez, 2005; Carlos A. Segovia and Basil Lourié, 2012; Emilio González Ferrín, 2013;) and its beginnings (Yehuda D. Nevo and Judith Koren, 2000; Alfred-Louis de Prémare, 2002; Karl-Heinz Ohlig and Gerd R. Puin, 2010; Françoise Micheau, 2012), the authenticity of the Qur'an (Mondher Sfar, 2000) and its possible Syro-Aramaic subtexts (Christoph Luxenberg, 2000), the origins and function of the Quranic collection and the results of its contemporary study with the tools of Biblical criticism (de Prémare, 2005; Manfred Kropp, 2007; Karl-Friedrich Pohlmann, 2012), the Qur'an's historical context and its Biblical subtexts (Gabriel Said Reynolds, 2008, 2010, 2012), its complex textuality (Michel Cuypers and Geneviève Gobillot, 2007), its canonisation and sacred character (M. Daniel De Smet, Godefroid Callatay and Jan M. F. Van Reeth, 2004), Muhammad's biography (David S. Powers, 2009; Stephen J. Shoemaker, 2011), the making of the early Islamic tradition (Berg, 2000; Bashear, 2004; Boaz Shoshan, 2004; Reynolds, 2012), the reworking of Biblical figures in early Islam (Guillaume Dye and Fabien Nobilio, 2012) and early Islamic apocalypticism (David Cook, 2002). But challenging the ordinary picture of Islam's origins is only the more evident purpose of the most salient of these studies, the essential one being an in-depth and more scientific re-examination of the complex processes that led to its formation. In order to fulfil this task, however, it seems necessary to assume once and for all the methodological theses perspicaciously formulated by Aaron W. Hughes in his recent work Theorizing Islam: Disciplinary Deconstruction and Reconstruction (2012): "[1] We must cease treating Islam . . . and Islamic data as if they were somehow special or privileged objects of study. [2] It is time to identify all those approaches that masquerade as critical scholarship for what they are. [3] We must ask of Islamic data what we would of any data. [4] Islamic studies must appeal to the theoretical framework of other disciplines. [5] Finally, Islamic studies must integrate itself with those critical discourses within the academic study of religion that are non-phenomenological."

It should also be mentioned, to end with, that the field of early islamic studies is now benefiting from the progress underway in the neighbouring field of late-antique Arab and Near-Eastern studies (on which see the recent contributions by Irfan Shahid [1984, 1989, 1995]; Jan Retsö [2003]; Iwona Gajda [2009]; Joëlle Beaucamp, Françoise Briquel-Chatonnet and Christian Robin [2010]; Greg Fisher [2011, 2013]; Glen W. Bowersock [2012, 2013]; Averil Cameron and Hoyland [2011, 2013]; and Griffith [2013]).

Pages in category "Early Islamic Studies"

The following 155 pages are in this category, out of 155 total.

- Early Islamic Studies (1450s)

- Early Islamic Studies (1500s)

- Early Islamic Studies (1600s)

- Early Islamic Studies (1700s)

- Early Islamic Studies (1800s)

- Early Islamic Studies (1850s)

- Early Islamic Studies (1900s)

- Early Islamic Studies (1910s)

- Early Islamic Studies (1920s)

- Early Islamic Studies (1930s)

- Early Islamic Studies (1940s)

- Early Islamic Studies (1950s)

- Early Islamic Studies (1960s)

- Early Islamic Studies (1970s)

- Early Islamic Studies (1980s)

- Early Islamic Studies (1990s)

- Early Islamic Studies (2000s)

- Early Islamic Studies (2010s)

- Early Islamic Studies (2020s)

*

- Early Islamic Studies (Afrikaans language)

- Early Islamic Studies (Albanian language)

- Early Islamic Studies (Arabic language)

- Early Islamic Studies (Bulgarian language)

- Early Islamic Studies (Chinese language)

- Early Islamic Studies (Croatian language)

- Early Islamic Studies (Czech language)

- Early Islamic Studies (Danish language)

- Early Islamic Studies (Dutch language)

- Early Islamic Studies (English language)

- Early Islamic Studies (Estonian language)

- Early Islamic Studies (Finnish language)

- Early Islamic Studies (French language)

- Early Islamic Studies (German language)

- Early Islamic Studies (Italian language)

- Early Islamic Studies (Japanese language)

- Early Islamic Studies (Latin language)

- Early Islamic Studies (Polish language)

- Early Islamic Studies (Portuguese language)

- Early Islamic Studies (Russian language)

- Early Islamic Studies (Serbian language)

- Early Islamic Studies (Spanish language)

C

- הקוראן = The Koran: A Very Short Introduction (2008 Cook / Bar-Asher, Tsafrir), book (Hebrew ed.)

- Temple et contemplation (Temple and Contemplation / 1980 Corbin), book

- The Event of the Qur'an: Islam in Its Scripture (1971 Cragg), book

- The Mind of the Qur'an: Chapters in Reflection (1973 Cragg), book

- Readings in the Qur'ān (1988 Cragg), book

D

G

- Une approche du Coran par la grammaire et le lexique (An Approach to the Qur’an through Its Grammar and Lexicon / 2002 Gloton), book

- Bibel und Koran: was sie verbindet, was sie trennt (Bible and Qur'an: What Unites, What Divides / 2004 Gnilka), book

- Islamic Christianity: An Account of References to Christianity in the Quran (2000 Gohari), book

- La palabra descendida: Un acercamiento al Corán (The Descended Word: An Approach to the Qur'an / 2002 González Ferrín), book

- Divine Word and Prophetic Word in Early Islam (1977 Graham), book

- The Temple of Solomon: Archaeological Fact and Medieval Tradition in Christian, Islamic, and Jewish Art (1976 Gutmann), book

- Koran und Koranexegese (The Qur'an and Its Exegesis / 1971 Gätjie), book

H

- Judaism and Islam: Boundaries, Communication, and Interaction (2000 Hary, Hayes, Astren), edited volume

- The First Dynasty of Islam: The Umayyad Caliphate AD 661-750 (1986 Hawting), book

- The Idea of Idolatry and the Emergence of Islam: From Polemic to History (1999 Hawting), book

- The Development of Islamic Ritual (2004 Hawting), book

- The Termination of Hostilities in the Early Arab Conquest (1971 Hill), book

- Beiträge zur Erklärung des Korân (A Contribution to the Study of the Qur'an / 1886 Hirschfeld), book

- Arabia and the Arabs: From the Bronze Age to the Coming of Islam (2001 Hoyland), book

J

- Bayt al-Maqdis: Jerusalem and Early Islam (2000 Johns), book

- Les Grands thèmes du Coran (The Great Themes of the Qur'an / 1978 Jomier), book

- Dieu et l'homme dans le Coran (God and Mankind in the Qur'an / 1996 Jomier), book

- Muslim Tradition: Studies in Chronology, Provenance, and Authorship of Early Hadith (1983 Juynboll), book

- Studies on the Origins and Uses of Islamic Hadith (1996 Juynboll), book

K

- Gott ist schön: das ästhetische Erleben des Koran (God is Beauty: An Aesthetical Approach to the Qur'an / 1999 Kermani), book

- Studies in Jāhiliyya and Early Islam (1980 Kister), book

- Society and Religion from Jahiliyya to Islam (1990 Kister), book

- Results of Contemporary Research on the Qur'an (2007 Kropp), edited volume

L

M

- The Succession to Muhammad: A Study of the Early Caliphate (1997 Madelung), book

- The Qur'an Self-Image: Writing and Authority in Islam's Scripture (2001 Madigan), book

- God, Muhammad and the Unbelievers: A Qur'anic Study (1999 Marshall), book

- Rituals of Islamic Monarchy: Accession and Succession in the First Muslim Empire (2009 Marsham), book

- Qur'anic Christians: An Analysis of Classical and Modern Exegesis (1991 McAuliffe), book

- Encyclopaedia of the Qur'an (2001-06 McAuliffe), edited volume

- Rhétorique sémitique. Textes de la Bible et de la Tradition musulmane (Semitic Rhetoric: Texts from the Bible and the Muslim Tradition / 1998 Meynet, Pouzet, Farouki, Sinno), book

- The Biography of Muhammad: The Issue of the Sources (2000 Motzki), book

- The Corân: Its Composition and Teaching, 2nd ed. (1896 Muir), book

- Untersuchungen zur Reimprosa im Koran (Investigations into the Rhymed Prose of the Qur'an / 1969 Müller), book

R

- The Arabs in Antiquity: Their History from the Assyrians to the Umayyads (2003 Retsö), book

- New Perspectives on the Qur'an: The Qur'an in Its Historical Context 2 (2011 Reynolds), edited volume

- The Emergence of Islam: Classical Traditions in Contemporary Perspective (2012 Reynolds), book

- Approaches to the History of the Interpretation of the Qur'ān (1988 Rippin), book

- Muslims: Their Religious Beliefs and Practices 1 (1990 Rippin), book

- The Qur'an: Formative Interpretation (1999 Rippin), edited volume

- The Qur'an: Style and Contents (1999 Rippin), book

- Discovering the Qur'an: A Contemporary Approach to a Veiled Text (1996 Robinson), book

- Islamic Historiography (2003 Robinson), book

- Empire and Elites after the Muslim Conquest: The Transformation of Northern Mesopotamia (2004 Robinson), book

- The Eye of the Beholder: The Life of Muhammad as Viewed by the Early Muslims (1995 Rubin), book

- The Life of Muhammad (1998 Rubin), edited volume

- The Idea of Divine Hardening: A Comparative Study of the Notion of Divine Hardening, Leading Astray and Inciting to Evil in the Bible and the Qur'an (1972 Räisänen), book

S

- Charakter und Authentie der muslimischen Überlieferung über das Leben Mohammeds (Character and Authenticity of Muhammad's Biographic Traditions / 1996 Schoeler), book

- Biblical and Extra-Biblical Legends in Islamic Folk-Literature (1982 Schwarzbaum), book

- Studies in Arabian History and Civilization (1981 Serjeant), book

~

- Peter Abelard (F / France / 1079-1142), scholar

- Robert of Ketton (M / Britain, Spain, 1110? – 1160?), scholar

- Yehuda Halevi (M / Spain, 1075/85-1141), scholar

- Mark of Toledo (M / Spain, d.1216), scholar

- Ramon Llull (M / Spain, 1232c-1315), scholar

- Nicolaus Cusanus (M / Germany, 1401-1464), scholar

- Giovanni Pico della Mirandola (M / Italy, 1463-1494), scholar

- Theodor Bibliander (1506-1564), scholar

- Andrea Arrivabene (M / Italy, 1510?-1570?), scholar

- Guillaume Postel (M / France, 1510-1581), scholar

- Johannes Drusius (M / Netherlands, 1550-1616), scholar

- Salomon Schweigger (M / Germany, 1551–1622), scholar

- André Du Ryer (M / France, 1580c-1660), scholar

- Alexander Ross (1591-1664), scholar

- Ludovico Marracci (M / Italy, 1612-1700), scholar

- Jan Hendrik Glazemaker (M / Netherlands, 1620–1682), scholar

- Johann Heinrich Hottinger (1620-1667), scholar

- Daniel de Larroque (1660-1731), translator

- Peter V. Postnikov (M / Russia, 18th cent.), scholar

- Jean Gagnier (1670c-1740), scholar

- Simon Ockley (1678-1720), scholar

- Voltaire (M / France, 1694-1778), playwright

- François Henri Turpin (1709-1799), scholar

- Mikhail I. Verevkin (M / Russia, 1732-1795), scholar

- Giovanni Bernardo De Rossi (M / Italy, 1742-1831), scholar

- João José Pereira (18th cent.), scholar

- Friedrich Rückert (M / Germany, 1788-1866), scholar, playwright

- Gustav Flügel (1802–1870), scholar

- Carl Johan Tornberg (M / Sweden, 1807-1877), scholar

- George Henry Miles (1824–1871), playwright

- Ignác Goldziher (1850-1921), scholar

- ~ Charles Cutler Torrey (1863-1956), American scholar

- Karl Vilhelm Zetterstéen (M / Sweden, 1866-1953), scholar

- Lazarus Goldschmidt (1871-1950), scholar

- Umberto Rizzitano (1913-1980), scholar

- Ivan Hrbek (M / Czechia, 1923-1993), scholar

- Desmond Stewart (1924-1981), British author

- Francis E. Peters (b.1927), scholar

- Mohammed Arkoun (1928-2010), scholar

- Joachim Gnilka (1928-2018), scholar

- Mikel de Epalza Ferrer (1938-2008), scholar

- Michael Cook (b.1940), scholar

- Martin Hinds (1941-1988), scholar

- Anne-Marie Delcambre (b.1943), scholar

- Karen Armstrong (b.1944), nonfiction writer

- Uri Rubin (b.1944), scholar

- Gregor Schoeler (b.1944), scholar

- Patricia Crone (b.1945), scholar

- Fred M. Donner (b.1945), scholar

- Lesley Hazleton (b.1945), nonfiction writer

- Mona Siddiqui

- Jane Dammen McAuliffe

- Martin R. Zammit

Media in category "Early Islamic Studies"

This category contains only the following file.

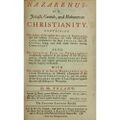

- 1718 Toland.jpg 500 × 500; 135 KB