Difference between revisions of "Category:Early Islamic Studies"

| Line 29: | Line 29: | ||

The founding in Paris in 1795 of the École Spéciale des Langues Orientales Vivantes marks off the beginnings of modern Islamic studies, for it was under the school's second director, [[Antoine Isaac Silvestre de Sacy]], that the first systematic curriculum for the teaching of Islamic languages, culture and civilisation was established in Europe. Yet the modern study of the [[Qur'an]] began with [[Gustav Flügel]] (1802-1870), [[Gustav Weil]] (1808-1889) and [[Theodor Nöldeke]] (1836-1930) in Germany. Flügel published the first modern edition of the [[Qur'an]] in 1834 (which was largely used before the Royal Cairo edition of 1923) and a Concordance to its Arabic text in 1842, whereas both Weil and Nöldeke published in 1844 and 1860, respectively, two historical-critical introductions to the Quranic ''textus receptus'' of which Weil's knew a second edition in 1878 and Nöldeke's, initially published in Latin in 1856 and later completed by Friedrich Schwally (in 1909 and 1919) and Gotthelf Bergsträsser and Otto Pretzl (in 1938), soon became the seminal and most authoritative work in the field, gaining wide, even uncontested reputation until the present day. As to [[Muhammad]], the first modern studies were those published by [[Abraham Geiger]] (1810-1878) in 1833, [[Gustav Weil]] in 1843, [[Aloys Sprenger]] (1813-1893) between 1861 and 1865, [[William Muir]] (1819-1905) between 1858 and 1861, and again Nöldeke in 1863. Geiger's pioneering essay on [[Muhammad]]'s life was also the first work to explore a number of possible early Islamic borrowings from Judaism, whilst its apparent Christian influences (on which a few authors like [[Ignaz Goldziher]] and [[Henry Preserved Smith]] already had provided some useful insights in the second half of the 19th century) were first systematically explored by [[Carl Heinrich Becker]] in 1907. But modern scholarship on Islam's origins is indebted too to the groundbreaking works of [[Ignaz Goldziher]] (1850-1921), whose ''Muhammedanische Studien'', published in 2 vols. between 1889 and 1890, represented a first, successful and in many ways still valid attempt to thoroughly examine the making and early development of Islamic identity, and its literature, against their complex historical and religious setting. | The founding in Paris in 1795 of the École Spéciale des Langues Orientales Vivantes marks off the beginnings of modern Islamic studies, for it was under the school's second director, [[Antoine Isaac Silvestre de Sacy]], that the first systematic curriculum for the teaching of Islamic languages, culture and civilisation was established in Europe. Yet the modern study of the [[Qur'an]] began with [[Gustav Flügel]] (1802-1870), [[Gustav Weil]] (1808-1889) and [[Theodor Nöldeke]] (1836-1930) in Germany. Flügel published the first modern edition of the [[Qur'an]] in 1834 (which was largely used before the Royal Cairo edition of 1923) and a Concordance to its Arabic text in 1842, whereas both Weil and Nöldeke published in 1844 and 1860, respectively, two historical-critical introductions to the Quranic ''textus receptus'' of which Weil's knew a second edition in 1878 and Nöldeke's, initially published in Latin in 1856 and later completed by Friedrich Schwally (in 1909 and 1919) and Gotthelf Bergsträsser and Otto Pretzl (in 1938), soon became the seminal and most authoritative work in the field, gaining wide, even uncontested reputation until the present day. As to [[Muhammad]], the first modern studies were those published by [[Abraham Geiger]] (1810-1878) in 1833, [[Gustav Weil]] in 1843, [[Aloys Sprenger]] (1813-1893) between 1861 and 1865, [[William Muir]] (1819-1905) between 1858 and 1861, and again Nöldeke in 1863. Geiger's pioneering essay on [[Muhammad]]'s life was also the first work to explore a number of possible early Islamic borrowings from Judaism, whilst its apparent Christian influences (on which a few authors like [[Ignaz Goldziher]] and [[Henry Preserved Smith]] already had provided some useful insights in the second half of the 19th century) were first systematically explored by [[Carl Heinrich Becker]] in 1907. But modern scholarship on Islam's origins is indebted too to the groundbreaking works of [[Ignaz Goldziher]] (1850-1921), whose ''Muhammedanische Studien'', published in 2 vols. between 1889 and 1890, represented a first, successful and in many ways still valid attempt to thoroughly examine the making and early development of Islamic identity, and its literature, against their complex historical and religious setting. | ||

For the most part, however, and notwithstanding their intrinsic value, these early studies (save those of Geiger and especially Goldziher, which were little conventional in both their approach and conclusions) tended to adopt and either explicitly or implicitly subscribe, and thus validate, the grand narrative of Islam's origins provided in the early Islamic sources. This is particularly noticeable in Nöldeke's case, whose chronology of the [[Qur'an]] largely follows the traditional Muslim chronology, and whose approach to the Quranic text as a single-authored unitary document is nowadays considered too naif, and accordingly regarded as outdated, by an increasing number of scholars. After all Nöldeke had studied with, and was the most salient disciple of, [[Heinrich Ewald]] (1803-1875), a German conservative theologian and orientalist who opposed the new critical methods essayed by [[Ferdinand Christian Baur]] and the Tübingen School in the neighbouring field of early Christian studies. In Ewald's view, all a scholar of early Islam was expected to do was to learn as much Arabic as possible and willingly accept the traditional account of the rise of Islam provided in the early Islamic sources, which veracity, therefore, ought not to be questioned. Supported by Nöldeke and his followers | For the most part, however, and notwithstanding their intrinsic value, these early studies (save those of Geiger and especially Goldziher, which were little conventional in both their approach and conclusions) tended to adopt and either explicitly or implicitly subscribe, and thus validate, the grand narrative of Islam's origins provided in the early Islamic sources. This is particularly noticeable in Nöldeke's case, whose chronology of the [[Qur'an]] largely follows the traditional Muslim chronology, and whose approach to the Quranic text as a single-authored unitary document is nowadays considered too naif, and accordingly regarded as outdated, by an increasing number of scholars. After all Nöldeke had studied with, and was the most salient disciple of, [[Heinrich Ewald]] (1803-1875), a German conservative theologian and orientalist who opposed the new critical methods essayed by [[Ferdinand Christian Baur]] and the Tübingen School in the neighbouring field of early Christian studies. In Ewald's view, all a scholar of early Islam was expected to do was to learn as much Arabic as possible and willingly accept the traditional account of the rise of Islam provided in the early Islamic sources, which veracity, therefore, ought not to be questioned. Supported by Nöldeke and his followers, this view rapidly became mainstream and has been prevalent in the field with only very few exceptions ever since. | ||

Other likewise prominent works published in the late 19th century and the first half of the 20th century (up to the late 1950s) include those of [[Hartwig Hirschfeld]] (1878, 1886, 1902), [[William Muir]] (1878), [[Charles Cutler Torrey]] (1892), [[William St Clair Tindall]] (1905), [[Leone Caetani]] (1905-1926), [[Israel Schapiro]] (1907), [[Paul Casanova]] (1911-1924), [[Lazarus Goldschmidt]] (1916), Goldziher (1920), [[Wilhelm Rudolph]] (1922), [[Josef Horovitz]] (1936), [[Heinrich Speyer]] (1931), [[David Sidersky]] (1933), [[Anton Spitaler]] (1935), [[Richard Bell]] (1937-1939), [[Arthur Jeffery]] (1937, 1938), and [[Régis Blachère]] (1947, 1949-1950) on the [[Qur'an]]; [[David Samuel Margoliouth]] (1905, 1914), [[Arent Jan Wensinck]] (1908), Caetani (1910), [[Henri Lammens]] (1912, 1914, 1924), Bell (1926), [[Tor Andrae]] (1926, 1932), Blachère (1952), and [[William Montgomery Watt]] (1953, 1956) on [[Muhammad]] and the early History of Islam; and [[Samuel Marinus Zwemer]] (1012), [[Wilhelm Rudolph]] (1922), Margoliouth (1924), [[Heinrich Speyer]] (1931), Torrey (1933), [[Haim Zeev (Joachim Wilhelm) Hirschberg]] (1939), [[Solomon D. Goiten]] (1955), and [[Denise Masson]] (1958) on early Jewish-Christian-Muslim relations. | Other likewise prominent works published in the late 19th century and the first half of the 20th century (up to the late 1950s) include those of [[Hartwig Hirschfeld]] (1878, 1886, 1902), [[William Muir]] (1878), [[Charles Cutler Torrey]] (1892), [[William St Clair Tindall]] (1905), [[Leone Caetani]] (1905-1926), [[Israel Schapiro]] (1907), [[Paul Casanova]] (1911-1924), [[Lazarus Goldschmidt]] (1916), Goldziher (1920), [[Wilhelm Rudolph]] (1922), [[Josef Horovitz]] (1936), [[Heinrich Speyer]] (1931), [[David Sidersky]] (1933), [[Anton Spitaler]] (1935), [[Richard Bell]] (1937-1939), [[Arthur Jeffery]] (1937, 1938), and [[Régis Blachère]] (1947, 1949-1950) on the [[Qur'an]]; [[David Samuel Margoliouth]] (1905, 1914), [[Arent Jan Wensinck]] (1908), Caetani (1910), [[Henri Lammens]] (1912, 1914, 1924), Bell (1926), [[Tor Andrae]] (1926, 1932), Blachère (1952), and [[William Montgomery Watt]] (1953, 1956) on [[Muhammad]] and the early History of Islam; and [[Samuel Marinus Zwemer]] (1012), [[Wilhelm Rudolph]] (1922), Margoliouth (1924), [[Heinrich Speyer]] (1931), Torrey (1933), [[Haim Zeev (Joachim Wilhelm) Hirschberg]] (1939), [[Solomon D. Goiten]] (1955), and [[Denise Masson]] (1958) on early Jewish-Christian-Muslim relations. | ||

Revision as of 07:21, 12 January 2014

- BACK to the MAIN PAGE

- This page is edited by Carlos A. Segovia, Saint Louis University and Camilo José Cela University, Spain (text & bibliography), and Emilio González Ferrín, University of Seville, Spain (bibliography)

|

Overview

History The connections between formative Islam and late antique Judaism and Christianity have long deserved the attencion of scholars of Islamic origins. Since the 19th century Muhammad’s early Christian background, on the one hand, his complex attitude – and that of his immediate followers – towards both Jews and Christians, on the other hand, and finally the presence of Jewish and Christian religious motifs in the Quranic text and in the Hadith corpus have been widely studied in the West. Yet from the 1970s onwards, a seemingly major shift has taken place in the study of Islam origins. Whereas the grand narratives of Islamic origins traditionally contained in the earliest Muslim writings have been usually taken to describe with some accuracy the hypothetical emergence of Islam in mid-7th-century Arabia, they are nowadays increasingly regarded as too late and ideologically biased – in short, as too eulogical – to provide a reliable picture of Islamic origins. Accordingly, new timeframes going from the late 7th to the mid-8th century (i.e. from the Marwanids to the Abbasids) and alternative Syro-Palestinian and Mesopotamian spatial locations are currently being explored. On the other hand a renewed attention is also being paid to the once very plausible pre-canonical redactional and editorial stages of the Qur'an, a book whose core many contemporary scholars agree to be a kind of “palimpsest” originally formed by different, independent writings in which encrypted passages from the OT Pseudepigrapha, the NT Apocrypha and other writings of Jewish, Christian and Manichaean provenance may be found, and whose liturgical and/or homiletical function contrasts with the juridical purposes set forth and projected onto the Quranic text by the later established Muslim tradition. Likewise the earliest Islamic community is presently regarded by many scholars as a somewhat undetermined monotheistic group that evolved from an original Jewish-Christian milieu into a distinct Muslim group perhaps much later than commonly assumed and in a rather unclear way, either within or tolerated by the new Arab polity in the Fertile Crescent or outside and initially opposed to it. Finally the biography of Muhammad, the founding figure of Islam, has also been challenged in recent times due to the paucity and, once more, the late date and the apparently literary nature of the earliest biographical accounts at our disposal. In sum three overall trends define today the field of early Islamic studies: (a) the traditional Islamic view, which many non-Muslim scholars still uphold as well; (b) a number of radically revisionist views which have contributed to reshape afresh the contents, boundaries and themes of the field itself by reframing the methodological and hermeneutical categories required in the academic study of Islamic origins; and (c) several moderately revisionist views that stand half way between the traditional point of view and the radically revisionist views. Surveying the history of these three competing views and their different approaches to the manner in which Islam emerged, the role played by Muhammad and the nature of the Qur'an should provide a comprehensive overview of the significance of this particular field of research for late-antique religious studies, both Jewish and Christian. Early modern Islamic studies and the traditional approach to the origins of Islam, Muhammad and the Qur'an The founding in Paris in 1795 of the École Spéciale des Langues Orientales Vivantes marks off the beginnings of modern Islamic studies, for it was under the school's second director, Antoine Isaac Silvestre de Sacy, that the first systematic curriculum for the teaching of Islamic languages, culture and civilisation was established in Europe. Yet the modern study of the Qur'an began with Gustav Flügel (1802-1870), Gustav Weil (1808-1889) and Theodor Nöldeke (1836-1930) in Germany. Flügel published the first modern edition of the Qur'an in 1834 (which was largely used before the Royal Cairo edition of 1923) and a Concordance to its Arabic text in 1842, whereas both Weil and Nöldeke published in 1844 and 1860, respectively, two historical-critical introductions to the Quranic textus receptus of which Weil's knew a second edition in 1878 and Nöldeke's, initially published in Latin in 1856 and later completed by Friedrich Schwally (in 1909 and 1919) and Gotthelf Bergsträsser and Otto Pretzl (in 1938), soon became the seminal and most authoritative work in the field, gaining wide, even uncontested reputation until the present day. As to Muhammad, the first modern studies were those published by Abraham Geiger (1810-1878) in 1833, Gustav Weil in 1843, Aloys Sprenger (1813-1893) between 1861 and 1865, William Muir (1819-1905) between 1858 and 1861, and again Nöldeke in 1863. Geiger's pioneering essay on Muhammad's life was also the first work to explore a number of possible early Islamic borrowings from Judaism, whilst its apparent Christian influences (on which a few authors like Ignaz Goldziher and Henry Preserved Smith already had provided some useful insights in the second half of the 19th century) were first systematically explored by Carl Heinrich Becker in 1907. But modern scholarship on Islam's origins is indebted too to the groundbreaking works of Ignaz Goldziher (1850-1921), whose Muhammedanische Studien, published in 2 vols. between 1889 and 1890, represented a first, successful and in many ways still valid attempt to thoroughly examine the making and early development of Islamic identity, and its literature, against their complex historical and religious setting. For the most part, however, and notwithstanding their intrinsic value, these early studies (save those of Geiger and especially Goldziher, which were little conventional in both their approach and conclusions) tended to adopt and either explicitly or implicitly subscribe, and thus validate, the grand narrative of Islam's origins provided in the early Islamic sources. This is particularly noticeable in Nöldeke's case, whose chronology of the Qur'an largely follows the traditional Muslim chronology, and whose approach to the Quranic text as a single-authored unitary document is nowadays considered too naif, and accordingly regarded as outdated, by an increasing number of scholars. After all Nöldeke had studied with, and was the most salient disciple of, Heinrich Ewald (1803-1875), a German conservative theologian and orientalist who opposed the new critical methods essayed by Ferdinand Christian Baur and the Tübingen School in the neighbouring field of early Christian studies. In Ewald's view, all a scholar of early Islam was expected to do was to learn as much Arabic as possible and willingly accept the traditional account of the rise of Islam provided in the early Islamic sources, which veracity, therefore, ought not to be questioned. Supported by Nöldeke and his followers, this view rapidly became mainstream and has been prevalent in the field with only very few exceptions ever since. Other likewise prominent works published in the late 19th century and the first half of the 20th century (up to the late 1950s) include those of Hartwig Hirschfeld (1878, 1886, 1902), William Muir (1878), Charles Cutler Torrey (1892), William St Clair Tindall (1905), Leone Caetani (1905-1926), Israel Schapiro (1907), Paul Casanova (1911-1924), Lazarus Goldschmidt (1916), Goldziher (1920), Wilhelm Rudolph (1922), Josef Horovitz (1936), Heinrich Speyer (1931), David Sidersky (1933), Anton Spitaler (1935), Richard Bell (1937-1939), Arthur Jeffery (1937, 1938), and Régis Blachère (1947, 1949-1950) on the Qur'an; David Samuel Margoliouth (1905, 1914), Arent Jan Wensinck (1908), Caetani (1910), Henri Lammens (1912, 1914, 1924), Bell (1926), Tor Andrae (1926, 1932), Blachère (1952), and William Montgomery Watt (1953, 1956) on Muhammad and the early History of Islam; and Samuel Marinus Zwemer (1012), Wilhelm Rudolph (1922), Margoliouth (1924), Heinrich Speyer (1931), Torrey (1933), Haim Zeev (Joachim Wilhelm) Hirschberg (1939), Solomon D. Goiten (1955), and Denise Masson (1958) on early Jewish-Christian-Muslim relations. Moderately revisionist approaches Defenders of moderately revisionist approaches contend that even though some of the early written sources of Islam may date to a later period, they are reliable enough and offer us a fair picture of the events they comment upon or describe. Some of the details they provide us with might be contradictory and even doubtful, yet the master narrative that they support should remain unchallenged, as there is no real reason to question it. Radically revisionist approaches Conversely, defenders of radically revisionist approaches sustain that the whole narrative of Islamic origins must be revised, reframed, and retold differently. From "Islamic Religious Studies" to "New Islamic Studies"? |

Categories

Texts

Chronology

Languages

Countries

Learned Societies

Journals

|

Pages in category "Early Islamic Studies"

The following 155 pages are in this category, out of 155 total.

- Early Islamic Studies (1450s)

- Early Islamic Studies (1500s)

- Early Islamic Studies (1600s)

- Early Islamic Studies (1700s)

- Early Islamic Studies (1800s)

- Early Islamic Studies (1850s)

- Early Islamic Studies (1900s)

- Early Islamic Studies (1910s)

- Early Islamic Studies (1920s)

- Early Islamic Studies (1930s)

- Early Islamic Studies (1940s)

- Early Islamic Studies (1950s)

- Early Islamic Studies (1960s)

- Early Islamic Studies (1970s)

- Early Islamic Studies (1980s)

- Early Islamic Studies (1990s)

- Early Islamic Studies (2000s)

- Early Islamic Studies (2010s)

- Early Islamic Studies (2020s)

*

- Early Islamic Studies (Afrikaans language)

- Early Islamic Studies (Albanian language)

- Early Islamic Studies (Arabic language)

- Early Islamic Studies (Bulgarian language)

- Early Islamic Studies (Chinese language)

- Early Islamic Studies (Croatian language)

- Early Islamic Studies (Czech language)

- Early Islamic Studies (Danish language)

- Early Islamic Studies (Dutch language)

- Early Islamic Studies (English language)

- Early Islamic Studies (Estonian language)

- Early Islamic Studies (Finnish language)

- Early Islamic Studies (French language)

- Early Islamic Studies (German language)

- Early Islamic Studies (Italian language)

- Early Islamic Studies (Japanese language)

- Early Islamic Studies (Latin language)

- Early Islamic Studies (Polish language)

- Early Islamic Studies (Portuguese language)

- Early Islamic Studies (Russian language)

- Early Islamic Studies (Serbian language)

- Early Islamic Studies (Spanish language)

C

- הקוראן = The Koran: A Very Short Introduction (2008 Cook / Bar-Asher, Tsafrir), book (Hebrew ed.)

- Temple et contemplation (Temple and Contemplation / 1980 Corbin), book

- The Event of the Qur'an: Islam in Its Scripture (1971 Cragg), book

- The Mind of the Qur'an: Chapters in Reflection (1973 Cragg), book

- Readings in the Qur'ān (1988 Cragg), book

D

G

- Une approche du Coran par la grammaire et le lexique (An Approach to the Qur’an through Its Grammar and Lexicon / 2002 Gloton), book

- Bibel und Koran: was sie verbindet, was sie trennt (Bible and Qur'an: What Unites, What Divides / 2004 Gnilka), book

- Islamic Christianity: An Account of References to Christianity in the Quran (2000 Gohari), book

- La palabra descendida: Un acercamiento al Corán (The Descended Word: An Approach to the Qur'an / 2002 González Ferrín), book

- Divine Word and Prophetic Word in Early Islam (1977 Graham), book

- The Temple of Solomon: Archaeological Fact and Medieval Tradition in Christian, Islamic, and Jewish Art (1976 Gutmann), book

- Koran und Koranexegese (The Qur'an and Its Exegesis / 1971 Gätjie), book

H

- Judaism and Islam: Boundaries, Communication, and Interaction (2000 Hary, Hayes, Astren), edited volume

- The First Dynasty of Islam: The Umayyad Caliphate AD 661-750 (1986 Hawting), book

- The Idea of Idolatry and the Emergence of Islam: From Polemic to History (1999 Hawting), book

- The Development of Islamic Ritual (2004 Hawting), book

- The Termination of Hostilities in the Early Arab Conquest (1971 Hill), book

- Beiträge zur Erklärung des Korân (A Contribution to the Study of the Qur'an / 1886 Hirschfeld), book

- Arabia and the Arabs: From the Bronze Age to the Coming of Islam (2001 Hoyland), book

J

- Bayt al-Maqdis: Jerusalem and Early Islam (2000 Johns), book

- Les Grands thèmes du Coran (The Great Themes of the Qur'an / 1978 Jomier), book

- Dieu et l'homme dans le Coran (God and Mankind in the Qur'an / 1996 Jomier), book

- Muslim Tradition: Studies in Chronology, Provenance, and Authorship of Early Hadith (1983 Juynboll), book

- Studies on the Origins and Uses of Islamic Hadith (1996 Juynboll), book

K

- Gott ist schön: das ästhetische Erleben des Koran (God is Beauty: An Aesthetical Approach to the Qur'an / 1999 Kermani), book

- Studies in Jāhiliyya and Early Islam (1980 Kister), book

- Society and Religion from Jahiliyya to Islam (1990 Kister), book

- Results of Contemporary Research on the Qur'an (2007 Kropp), edited volume

L

M

- The Succession to Muhammad: A Study of the Early Caliphate (1997 Madelung), book

- The Qur'an Self-Image: Writing and Authority in Islam's Scripture (2001 Madigan), book

- God, Muhammad and the Unbelievers: A Qur'anic Study (1999 Marshall), book

- Rituals of Islamic Monarchy: Accession and Succession in the First Muslim Empire (2009 Marsham), book

- Qur'anic Christians: An Analysis of Classical and Modern Exegesis (1991 McAuliffe), book

- Encyclopaedia of the Qur'an (2001-06 McAuliffe), edited volume

- Rhétorique sémitique. Textes de la Bible et de la Tradition musulmane (Semitic Rhetoric: Texts from the Bible and the Muslim Tradition / 1998 Meynet, Pouzet, Farouki, Sinno), book

- The Biography of Muhammad: The Issue of the Sources (2000 Motzki), book

- The Corân: Its Composition and Teaching, 2nd ed. (1896 Muir), book

- Untersuchungen zur Reimprosa im Koran (Investigations into the Rhymed Prose of the Qur'an / 1969 Müller), book

R

- The Arabs in Antiquity: Their History from the Assyrians to the Umayyads (2003 Retsö), book

- New Perspectives on the Qur'an: The Qur'an in Its Historical Context 2 (2011 Reynolds), edited volume

- The Emergence of Islam: Classical Traditions in Contemporary Perspective (2012 Reynolds), book

- Approaches to the History of the Interpretation of the Qur'ān (1988 Rippin), book

- Muslims: Their Religious Beliefs and Practices 1 (1990 Rippin), book

- The Qur'an: Formative Interpretation (1999 Rippin), edited volume

- The Qur'an: Style and Contents (1999 Rippin), book

- Discovering the Qur'an: A Contemporary Approach to a Veiled Text (1996 Robinson), book

- Islamic Historiography (2003 Robinson), book

- Empire and Elites after the Muslim Conquest: The Transformation of Northern Mesopotamia (2004 Robinson), book

- The Eye of the Beholder: The Life of Muhammad as Viewed by the Early Muslims (1995 Rubin), book

- The Life of Muhammad (1998 Rubin), edited volume

- The Idea of Divine Hardening: A Comparative Study of the Notion of Divine Hardening, Leading Astray and Inciting to Evil in the Bible and the Qur'an (1972 Räisänen), book

S

- Charakter und Authentie der muslimischen Überlieferung über das Leben Mohammeds (Character and Authenticity of Muhammad's Biographic Traditions / 1996 Schoeler), book

- Biblical and Extra-Biblical Legends in Islamic Folk-Literature (1982 Schwarzbaum), book

- Studies in Arabian History and Civilization (1981 Serjeant), book

~

- Peter Abelard (F / France / 1079-1142), scholar

- Robert of Ketton (M / Britain, Spain, 1110? – 1160?), scholar

- Yehuda Halevi (M / Spain, 1075/85-1141), scholar

- Mark of Toledo (M / Spain, d.1216), scholar

- Ramon Llull (M / Spain, 1232c-1315), scholar

- Nicolaus Cusanus (M / Germany, 1401-1464), scholar

- Giovanni Pico della Mirandola (M / Italy, 1463-1494), scholar

- Theodor Bibliander (1506-1564), scholar

- Andrea Arrivabene (M / Italy, 1510?-1570?), scholar

- Guillaume Postel (M / France, 1510-1581), scholar

- Johannes Drusius (M / Netherlands, 1550-1616), scholar

- Salomon Schweigger (M / Germany, 1551–1622), scholar

- André Du Ryer (M / France, 1580c-1660), scholar

- Alexander Ross (1591-1664), scholar

- Ludovico Marracci (M / Italy, 1612-1700), scholar

- Jan Hendrik Glazemaker (M / Netherlands, 1620–1682), scholar

- Johann Heinrich Hottinger (1620-1667), scholar

- Daniel de Larroque (1660-1731), translator

- Peter V. Postnikov (M / Russia, 18th cent.), scholar

- Jean Gagnier (1670c-1740), scholar

- Simon Ockley (1678-1720), scholar

- Voltaire (M / France, 1694-1778), playwright

- François Henri Turpin (1709-1799), scholar

- Mikhail I. Verevkin (M / Russia, 1732-1795), scholar

- Giovanni Bernardo De Rossi (M / Italy, 1742-1831), scholar

- João José Pereira (18th cent.), scholar

- Friedrich Rückert (M / Germany, 1788-1866), scholar, playwright

- Gustav Flügel (1802–1870), scholar

- Carl Johan Tornberg (M / Sweden, 1807-1877), scholar

- George Henry Miles (1824–1871), playwright

- Ignác Goldziher (1850-1921), scholar

- ~ Charles Cutler Torrey (1863-1956), American scholar

- Karl Vilhelm Zetterstéen (M / Sweden, 1866-1953), scholar

- Lazarus Goldschmidt (1871-1950), scholar

- Umberto Rizzitano (1913-1980), scholar

- Ivan Hrbek (M / Czechia, 1923-1993), scholar

- Desmond Stewart (1924-1981), British author

- Francis E. Peters (b.1927), scholar

- Mohammed Arkoun (1928-2010), scholar

- Joachim Gnilka (1928-2018), scholar

- Mikel de Epalza Ferrer (1938-2008), scholar

- Michael Cook (b.1940), scholar

- Martin Hinds (1941-1988), scholar

- Anne-Marie Delcambre (b.1943), scholar

- Karen Armstrong (b.1944), nonfiction writer

- Uri Rubin (b.1944), scholar

- Gregor Schoeler (b.1944), scholar

- Patricia Crone (b.1945), scholar

- Fred M. Donner (b.1945), scholar

- Lesley Hazleton (b.1945), nonfiction writer

- Mona Siddiqui

- Jane Dammen McAuliffe

- Martin R. Zammit

Media in category "Early Islamic Studies"

This category contains only the following file.

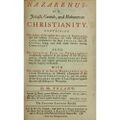

- 1718 Toland.jpg 500 × 500; 135 KB