Difference between revisions of "Category:Buchenwald (subject)"

| (23 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

'''Buchenwald''' | '''KZ Buchenwald''' (see [[Holocaust Children Studies]]) | ||

== | == Overview == | ||

'''Buchenwald''' was a concentration camp in Germany, one of the first and the largest of the concentration camps within Germany's 1937 borders. It was built mainly to accommodate political prisoners, but in the last months of a war a lot of inmates from concentration camps in the East (including children) were taken to Buchenwald. | |||

All prisoners worked primarily as forced labor in local armaments factories. The insufficient food and poor conditions, as well as deliberate executions, led to 56,545 deaths at Buchenwald of the 280,000 prisoners who passed through the camp and its 139 subcamps. | |||

== Liberation of Buchenwald == | |||

The establishment of the | On April 11th 1945, the 6th Armoured Division of the US army liberated Buchenwald concentration camp, making its inmates the first on German soil to be freed from the grip of the Nazis. By the end of the war, Buchenwald and its surrounding sub-camps made up the largest camp in Germany. | ||

== The Buchenwald Children == | |||

Buchenwald was a labor camp. It was not meant to host children, if not adolescents who were fit to work as adults. Oftentimes, children lied about their ages to make them older. If discovered they were sent to Auschwitz or Bergen-Belsen to be killed. | |||

In April 1943, there were only 142 inmates under the age of twenty. At this time, the smaller children were kept hidden in Block 8, located in the main camp. | |||

During the last year of the war, however the Nazis began sending large numbers of Jewish Eastern European children to Buchenwald as a result of their failing war efforts. The Nazis were forced to evacuate other camps due to the Allied Powers closing in on the German fronts. | |||

By the time December 1944 rolled around however, there were over 23,000 inmates under the age of 20, which was 37% percent of the population. The age group of specifically 14-18 year olds, was around eighty-five percent of the total number of children in the camp. | |||

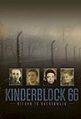

==== Block 66 ==== | |||

The establishment of the children's block was led by Antonin Kalina, a Czech communist prisoner.[1] Kalina, with the help of other political prisoners, was able to persuade the SS at Buchenwald to let them create a block for the new influx of adolescents coming in from the East.[8] The block used for the children was conveniently located in the corner of the little camp, ensuring that it was as far away from the Nazi's watch as possible.[1] | |||

Every block had what was called a “block elder” who was responsible for ensuring that the inmates of their block went to roll-call, followed orders, did their work, and kept up with their daily tasks.[1] The block elder of Block 66 was Kalina, and he is primarily responsible for saving the lives of the 900 boys living in Block 66. | Every block had what was called a “block elder” who was responsible for ensuring that the inmates of their block went to roll-call, followed orders, did their work, and kept up with their daily tasks.[1] The block elder of Block 66 was Kalina, and he is primarily responsible for saving the lives of the 900 boys living in Block 66. | ||

While conditions were not great anywhere in the camp, for the children of Block 66, they were slightly better. Unlike adults, most children could not fend off the disease, hunger, and physical and psychological trauma as well. Adults, specifically the communist prisoners directly tried to help the children. The other prisoners in Buchenwald did all that they could in their power to try and protect the children from the SS, and as the war was clearly ending, from being taken out on death marches.[8] Men would also give extra food to these starving boys and share packages from | While conditions were not great anywhere in the camp, for the children of Block 66, they were slightly better.[1] Unlike adults, most children could not fend off the disease, hunger, and physical and psychological trauma as well.[9] Adults, specifically the communist prisoners directly tried to help the children. The other prisoners in Buchenwald did all that they could in their power to try and protect the children from the SS, and as the war was clearly ending, from being taken out on death marches.[8] Men would also give extra food to these starving boys and share packages from the Red Cross with them.[1] Had there not been Block 66, most of these children would have perished in the camp.[8] | ||

The children were not made to work in the camp, as most were too weak and young to do any actual labor. During the days, when it was possible, the children were taught songs in Yiddish and told stories by some elders and older children to keep them occupied and filled with hope for the outside world.[1] | |||

Additionally, Kalina, to help protect the children in the barrack, made them change clothes, so as not to be dressed as Jews, and changed the Jewish sounding names of the boys, so that when the SS officers came by looking for Jews, he could tell them that there were none in his block. | |||

== Liberation == | |||

On April 11, 1945, at approximately 3:15 pm, Buchenwald was finally liberated by the U.S. Army; 21,000 inmates were liberated that day of which 904 were children. Among them were [[Elie Wiesel]], [[Imre Kertész]], [[Yisrael Meir Lau]], [[David Perlmutter]], [[Izio Rosenman]], [[Thomas Geve]], [[Gert Schramm]] (the youngest African-German inmate) and the 4-years-old [[Stefan Jerzy Zweig]] and [[Joseph Schleifstein]]. | |||

[[File:Buchenwald Boys.jpg|700px]] | |||

== | == After liberation == | ||

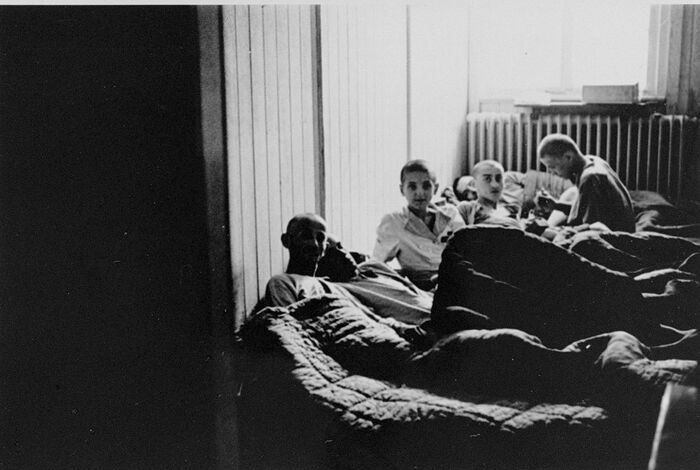

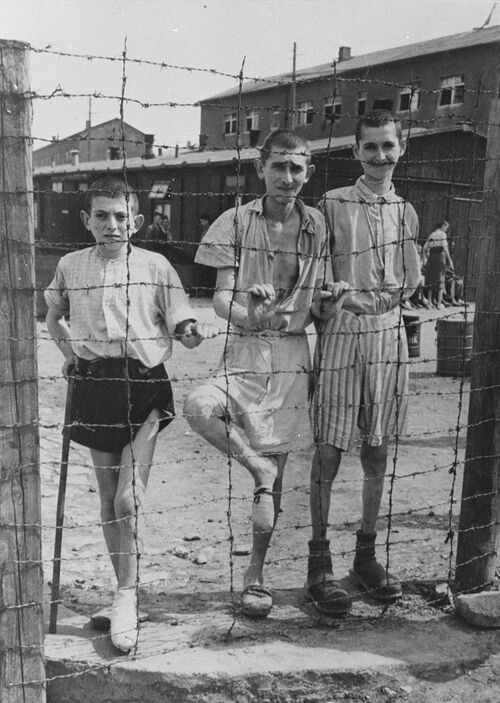

After liberation, most children remained at Buchewald where they received medical attention, food, new clothing. | |||

[[File:Buchenwald Children3.jpg|700px]] | |||

{Pictured on the far right is [[Salek Finkelstein]].} | |||

Many of the children needed time to recover, especially from frost-bite and malnutrition. | |||

[[File:Buchenwald Children4.jpg|700px]] | |||

[[File:Buchenwald Children6.jpg|700px]] | |||

[[File:Buchenwald Children8.jpg|500px]] | |||

[[ | [[File:Buchenwald Children5.jpg|700px]] | ||

Most of the children were originally from Poland, though others came from Hungary, Slovenia and Ruthenia. Most of them were teenagers, but there was also a small group of around 20 younger children, including two four-year-old boys, [[Joseph Schleifstein]] and [[Stefan Jerzy Zweig]]. | |||

[[File: | [[File:Buchenwald Children.jpg|700px]] | ||

* [https://collections.ushmm.org/search/catalog/pa1067603 USHMM Collections] -- Among those pictured are first row (left to right): Lolek Blum, [[David Perlmutter]], Birenbaum, [[Stefan Jerzy Zweig]], [[Stephen Jacobs]] (?) and [[Yisrael Meir Lau]] (middle row, far right). Middle row: Nathan Szwarc, Jack Neeman, Berek Silber, [[Jakub Finkelstajn]] (Jacques Finkel), unidentified, Marek Milstein, and [[Salek Finkelstein]]. Back row: Elek Grinbaum [or Grinberg], [[Chaim Finkelstajn]] (Charles Finkel), [[Romek Wajsman]] (Wekselman), and [[Abe Chapnick]]. The boys are dressed in outfits made from German uniforms due to a clothing shortage. | |||

[[File:Buchenwald Children2.jpg|700px]] | |||

In spite of the loss of their families and the uncertainties about the future, children enjoyed freedom and resumed their ties with their Jewish identity. American chaplain Rabbi Hershel Schaecter conducted Shavuot services for Buchenwald survivors shortly after liberation. | |||

[[ | [[File:Buchenwald Shavuot.jpg|700px]] | ||

== | == Leaving Buchenwald == | ||

Most children did not have a place to go. | |||

[[File:Buchenwald Children7.jpg|700px]] | |||

[ | Unsure of what to do with the child survivors, American army chaplains, Rabbi Herschel Schacter and Rabbi Robert Marcus, contacted the offices of the OSE (Oeuvre de Secours aux Enfants), the Jewish children's relief organization in Geneva. They arranged to send 427 of the children to France, 280 to Switzerland and 250 to England. [Vivette Samuels reverses the figures for England and Switzerland in her monograph, "Sauver les Enfants."] | ||

[[File: | [[File:Leaving Buchenwald France.jpg|700px]] | ||

[[File:Leaving Buchenwald France2.jpg|700px]] | |||

On June 2, 1945 OSE representatives arrived in Buchenwald, and together with Rabbi Marcus escorted the transport of children to France. Rabbi Schacter accompanied the second transport to Switzerland. Because of the difficulty in finding clothing for the children, the boys were clad in Hitler Youth uniforms. This created a problem, for when the train crossed into France, it was greeted by an angry populace who assumed the train was carrying Nazi youth. Thereafter the words "KZ Buchenwald orphans" were painted on the outside of the train to avoid confusion. On June 6, 1945 the French transport arrived at the Andelys station and the orphans were taken to a children's home in Ecouis (Eure). The home had been set up to accommodate young children, but in fact only 30 of the boys were below the age of 13. This was only one of the many problems faced by the OSE personnel, who were not prepared to handle a large group of demanding, rebellious teenagers who were full of anger for what they had experienced. At Ecouis the boys were given medical care, counseling and schooling until more permanent accommodations could be found. Most of the children remained only four to eight weeks at Ecouis before being moved elsewhere, and the home was closed in August 1945. Among the first to leave were a group of 173 children who had family in Palestine. They were given immigration certificates and departed from Marseilles in July aboard the British vessel, the RMS Mataroa. The remaining boys at Ecouis were soon transferred to other residences and homes. Some of the older ones were sent to the Foyer d'Etudiants located on the rue Rollin in Paris, where they boarded while attending vocational training courses or working at jobs in the city. Others were sent to the Chateau de Boucicaut home in Fontenay-aux-Roses (Hauts-de-Seine). Many of the boys came from religiously observant homes. Since the OSE could not obtain kosher food for everyone, they divided the children into religious and non-religious groups. Dr. Charly Merzbach offered OSE the use of his estate, the Chateau d'Ambloy (Loir-et-Cher) for the summer, and between 90 and 100 boys chose to go there in order to receive kosher food and live in a religious environment. In October 1945 the children and staff of Ambloy were relocated to the Chateau de Vaucelles in Taverny (Val d'Oise). About 50 of the non-religious boys were taken to the Villa Concordiale in Le Vesinet (Yvelines) near Paris that housed an equal number of French Jewish orphans. In the summer they went to the Foyer de Champigny in Champigny-sur-Marne (Val-de-Marne). In all the homes attended by the Buchenwald children vocational training as well as regular classroom instruction was offered. At the same time OSE social workers made every effort to locate surviving relatives, succeeding in about half the cases. By the end of 1948 all of the Buchenwald children who had come to France had left the OSE fold and begun new lives for themselves. | |||

== | == Switzerland == | ||

On June 23, 1945, 350 young people and children from Buchenwald arrived in Switzerland. She was accompanied by Rabbi Herschel Schacter, who, as a member of the US Army, looked after the liberated Jews in Buchenwald. What preceded that? | |||

On April 22, 1945, eleven days after the Buchenwald concentration camp was liberated, the Jewish Aid Committee went public with an appeal: “Save the rest of the Jewish youth in Central Europe!” On the same day, Herschel Schacter wrote a request for help to the Œuvre de office secours aux enfants (OSE) in Geneva. The Jewish Children's Fund, based in Paris, reacted immediately, and Jewish organizations in Switzerland, France and the USA looked for opportunities to take in the young people. The United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration (UNRRA) and the Red Cross helped. | |||

Shavuot celebration with Rabbi Herschel Schacter in the cinema barrack in Buchenwald, May 18, 1945. | |||

Photo: Charles W. Herr (National Archives at College Park, Maryland) | |||

The majority of the 904 minors who were counted among the survivors of the camp in mid-April 1945 were older than 15 years. The few children among them survived through the solidarity of political prisoners. The youngest, four-year-old Janek Szlajfstajn and Stefan Jerzy Zweig, were hidden in the prisoner infirmary and in the small camp; Soviet prisoners hid 11-year-old Menek Schiller in Block 30; his two-year-old brother survived with other children under the protection of the Jewish prisoners in Block 23; 6-year-old Isaak Goldblum was accommodated in “Children's Block 66” in the Small Camp and 7-year-old Israel Lau in “Children's Block 8”. | |||

Janek Szlajfstajn, the youngest survivor of Buchenwald, before leaving for Switzerland, June 19, 1945. | |||

Photo: George A. Haynia (National Archives at College Park, Maryland) | |||

Most of the Jewish youth in Buchenwald were orphans without a home. The Schiller brothers found their mother in the former Meuselwitz subcamp. Individuals joined their national group trips home. The 17-year-old Leopold Huppert drove to Prague with the liberated Czechs in May 1945. He and other young people from Theresienstadt, Dachau and Buchenwald were accepted at Štiřín Castle. There was one of the rest homes that the pedagogue Přemysl Pitter had opened to take in orphaned Jewish youths in vacant castles. | |||

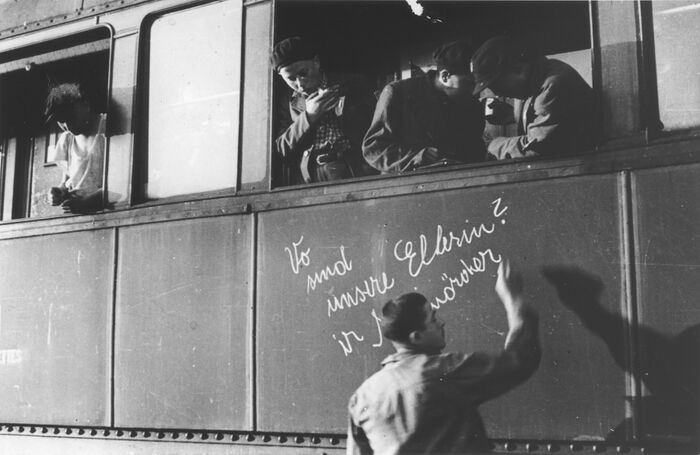

Departure of the train for France from Buchenwald station, June 5, 1945. | |||

Photo: James E. Myers (National Archives at College Park, Maryland) | |||

On June 5, 1945, the first passenger train with Jewish youth and children left Weimar station. 427 young people - boys from Buchenwald and girls from Bergen-Belsen - drove to the French town of Écouis, where they were warmly welcomed. They should recover, connect with loved ones and decide on their future path. In addition to France and Switzerland, Great Britain also took in hundreds of young Jews in the summer of that year. | |||

Before leaving for France, June 5, 1945. | |||

(Willy Fogel; Buchenwald Memorial) | |||

"Vo are our parents? ir Nazi murderers… ”wrote 15-year-old Josek Dziubak, one of the boys from Block 66, in chalk on one of the trains to France. It took him two years to find relatives who brought him to the United States. Another member of the group, Robert Wajcman, said of the photo many years later: “Joe really spoke for us all. We had all just begun to understand how few of our family members were still alive. " | |||

== Children in Block 66 == | |||

* [[Jacques Ribons]] / Jakob Rybsztajn''' (M / Poland, 1927) | |||

* [[Henry Kinast]] (M / 1929) | |||

* [[Bernard Ribons]] / Berek Rybsztajn (M / Poland, 1929-2011) | |||

* [[Thomas Geve]] | |||

[[Naftali Fürst]], [[Pavel Kohn]], [[Israel-Laszlo Lazar]] and [[Alex Moskovic]] | |||

==== Other prisoners of Block 66 ==== | |||

* [[Frank Dobia]] (b.1926) | |||

== Children in Block 8 == | |||

* [[Elie Buzyn]] (M / Poland, 1929) | |||

* [[Zoltan Blau]] (M / Hungary, 1930) | |||

* [[Abe Chapnick]] (M / Poland, 1930-2016) | |||

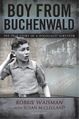

* [[Romek Wajsman]] / Robbie Waisman (M / Poland, 1931) | |||

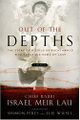

* [[Yisrael Meir Lau]] (M / Poland, 1937) | |||

==Child survivors== | ==Child survivors== | ||

| Line 141: | Line 164: | ||

* Joe Majer = Salomon Majer | * Joe Majer = Salomon Majer | ||

* Philip Kanner = Fajwen Kaner | * Philip Kanner = Fajwen Kaner | ||

* Jerry Kapelus = Jakob Kapelusz | * [[Jerry Kapelus]] = Jakob Kapelusz | ||

* Ted "Booby" Lowy (Lewy) = Theodor Lowy | * Ted "Booby" Lowy (Lewy) = Theodor Lowy | ||

* Eddy Balter = Elias Balter | * Eddy Balter = Elias Balter | ||

* Willy Fogel = Wolf Vogel / Wolf Fojgel | * [[Willy Fogel]] = Wolf Vogel / Wolf Fojgel | ||

* Max Kosuch | * Max Kosuch | ||

* Robbie Waisman = Romek Wajsman | * Robbie Waisman = [[Romek Wajsman]] | ||

* Leon Friedman | * Leon Friedman | ||

* Szaja Chaskiel | * Szaja Chaskiel | ||

| Line 156: | Line 179: | ||

Yossl Baker, Henry Salter | Yossl Baker, Henry Salter | ||

[[Kuba Enoch]], [[George Grojnowski]] and [[Jack Meister]] (see YouTube) | |||

== External links == | |||

[[ | * [[Buchenwald Children France]] | ||

* [[Buchenwald Children Switzerland]] | |||

Latest revision as of 13:56, 12 May 2023

KZ Buchenwald (see Holocaust Children Studies)

Overview

Buchenwald was a concentration camp in Germany, one of the first and the largest of the concentration camps within Germany's 1937 borders. It was built mainly to accommodate political prisoners, but in the last months of a war a lot of inmates from concentration camps in the East (including children) were taken to Buchenwald.

All prisoners worked primarily as forced labor in local armaments factories. The insufficient food and poor conditions, as well as deliberate executions, led to 56,545 deaths at Buchenwald of the 280,000 prisoners who passed through the camp and its 139 subcamps.

Liberation of Buchenwald

On April 11th 1945, the 6th Armoured Division of the US army liberated Buchenwald concentration camp, making its inmates the first on German soil to be freed from the grip of the Nazis. By the end of the war, Buchenwald and its surrounding sub-camps made up the largest camp in Germany.

The Buchenwald Children

Buchenwald was a labor camp. It was not meant to host children, if not adolescents who were fit to work as adults. Oftentimes, children lied about their ages to make them older. If discovered they were sent to Auschwitz or Bergen-Belsen to be killed.

In April 1943, there were only 142 inmates under the age of twenty. At this time, the smaller children were kept hidden in Block 8, located in the main camp.

During the last year of the war, however the Nazis began sending large numbers of Jewish Eastern European children to Buchenwald as a result of their failing war efforts. The Nazis were forced to evacuate other camps due to the Allied Powers closing in on the German fronts.

By the time December 1944 rolled around however, there were over 23,000 inmates under the age of 20, which was 37% percent of the population. The age group of specifically 14-18 year olds, was around eighty-five percent of the total number of children in the camp.

Block 66

The establishment of the children's block was led by Antonin Kalina, a Czech communist prisoner.[1] Kalina, with the help of other political prisoners, was able to persuade the SS at Buchenwald to let them create a block for the new influx of adolescents coming in from the East.[8] The block used for the children was conveniently located in the corner of the little camp, ensuring that it was as far away from the Nazi's watch as possible.[1]

Every block had what was called a “block elder” who was responsible for ensuring that the inmates of their block went to roll-call, followed orders, did their work, and kept up with their daily tasks.[1] The block elder of Block 66 was Kalina, and he is primarily responsible for saving the lives of the 900 boys living in Block 66.

While conditions were not great anywhere in the camp, for the children of Block 66, they were slightly better.[1] Unlike adults, most children could not fend off the disease, hunger, and physical and psychological trauma as well.[9] Adults, specifically the communist prisoners directly tried to help the children. The other prisoners in Buchenwald did all that they could in their power to try and protect the children from the SS, and as the war was clearly ending, from being taken out on death marches.[8] Men would also give extra food to these starving boys and share packages from the Red Cross with them.[1] Had there not been Block 66, most of these children would have perished in the camp.[8]

The children were not made to work in the camp, as most were too weak and young to do any actual labor. During the days, when it was possible, the children were taught songs in Yiddish and told stories by some elders and older children to keep them occupied and filled with hope for the outside world.[1]

Additionally, Kalina, to help protect the children in the barrack, made them change clothes, so as not to be dressed as Jews, and changed the Jewish sounding names of the boys, so that when the SS officers came by looking for Jews, he could tell them that there were none in his block.

Liberation

On April 11, 1945, at approximately 3:15 pm, Buchenwald was finally liberated by the U.S. Army; 21,000 inmates were liberated that day of which 904 were children. Among them were Elie Wiesel, Imre Kertész, Yisrael Meir Lau, David Perlmutter, Izio Rosenman, Thomas Geve, Gert Schramm (the youngest African-German inmate) and the 4-years-old Stefan Jerzy Zweig and Joseph Schleifstein.

After liberation

After liberation, most children remained at Buchewald where they received medical attention, food, new clothing.

{Pictured on the far right is Salek Finkelstein.}

Many of the children needed time to recover, especially from frost-bite and malnutrition.

Most of the children were originally from Poland, though others came from Hungary, Slovenia and Ruthenia. Most of them were teenagers, but there was also a small group of around 20 younger children, including two four-year-old boys, Joseph Schleifstein and Stefan Jerzy Zweig.

- USHMM Collections -- Among those pictured are first row (left to right): Lolek Blum, David Perlmutter, Birenbaum, Stefan Jerzy Zweig, Stephen Jacobs (?) and Yisrael Meir Lau (middle row, far right). Middle row: Nathan Szwarc, Jack Neeman, Berek Silber, Jakub Finkelstajn (Jacques Finkel), unidentified, Marek Milstein, and Salek Finkelstein. Back row: Elek Grinbaum [or Grinberg], Chaim Finkelstajn (Charles Finkel), Romek Wajsman (Wekselman), and Abe Chapnick. The boys are dressed in outfits made from German uniforms due to a clothing shortage.

In spite of the loss of their families and the uncertainties about the future, children enjoyed freedom and resumed their ties with their Jewish identity. American chaplain Rabbi Hershel Schaecter conducted Shavuot services for Buchenwald survivors shortly after liberation.

Leaving Buchenwald

Most children did not have a place to go.

Unsure of what to do with the child survivors, American army chaplains, Rabbi Herschel Schacter and Rabbi Robert Marcus, contacted the offices of the OSE (Oeuvre de Secours aux Enfants), the Jewish children's relief organization in Geneva. They arranged to send 427 of the children to France, 280 to Switzerland and 250 to England. [Vivette Samuels reverses the figures for England and Switzerland in her monograph, "Sauver les Enfants."]

On June 2, 1945 OSE representatives arrived in Buchenwald, and together with Rabbi Marcus escorted the transport of children to France. Rabbi Schacter accompanied the second transport to Switzerland. Because of the difficulty in finding clothing for the children, the boys were clad in Hitler Youth uniforms. This created a problem, for when the train crossed into France, it was greeted by an angry populace who assumed the train was carrying Nazi youth. Thereafter the words "KZ Buchenwald orphans" were painted on the outside of the train to avoid confusion. On June 6, 1945 the French transport arrived at the Andelys station and the orphans were taken to a children's home in Ecouis (Eure). The home had been set up to accommodate young children, but in fact only 30 of the boys were below the age of 13. This was only one of the many problems faced by the OSE personnel, who were not prepared to handle a large group of demanding, rebellious teenagers who were full of anger for what they had experienced. At Ecouis the boys were given medical care, counseling and schooling until more permanent accommodations could be found. Most of the children remained only four to eight weeks at Ecouis before being moved elsewhere, and the home was closed in August 1945. Among the first to leave were a group of 173 children who had family in Palestine. They were given immigration certificates and departed from Marseilles in July aboard the British vessel, the RMS Mataroa. The remaining boys at Ecouis were soon transferred to other residences and homes. Some of the older ones were sent to the Foyer d'Etudiants located on the rue Rollin in Paris, where they boarded while attending vocational training courses or working at jobs in the city. Others were sent to the Chateau de Boucicaut home in Fontenay-aux-Roses (Hauts-de-Seine). Many of the boys came from religiously observant homes. Since the OSE could not obtain kosher food for everyone, they divided the children into religious and non-religious groups. Dr. Charly Merzbach offered OSE the use of his estate, the Chateau d'Ambloy (Loir-et-Cher) for the summer, and between 90 and 100 boys chose to go there in order to receive kosher food and live in a religious environment. In October 1945 the children and staff of Ambloy were relocated to the Chateau de Vaucelles in Taverny (Val d'Oise). About 50 of the non-religious boys were taken to the Villa Concordiale in Le Vesinet (Yvelines) near Paris that housed an equal number of French Jewish orphans. In the summer they went to the Foyer de Champigny in Champigny-sur-Marne (Val-de-Marne). In all the homes attended by the Buchenwald children vocational training as well as regular classroom instruction was offered. At the same time OSE social workers made every effort to locate surviving relatives, succeeding in about half the cases. By the end of 1948 all of the Buchenwald children who had come to France had left the OSE fold and begun new lives for themselves.

Switzerland

On June 23, 1945, 350 young people and children from Buchenwald arrived in Switzerland. She was accompanied by Rabbi Herschel Schacter, who, as a member of the US Army, looked after the liberated Jews in Buchenwald. What preceded that?

On April 22, 1945, eleven days after the Buchenwald concentration camp was liberated, the Jewish Aid Committee went public with an appeal: “Save the rest of the Jewish youth in Central Europe!” On the same day, Herschel Schacter wrote a request for help to the Œuvre de office secours aux enfants (OSE) in Geneva. The Jewish Children's Fund, based in Paris, reacted immediately, and Jewish organizations in Switzerland, France and the USA looked for opportunities to take in the young people. The United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration (UNRRA) and the Red Cross helped.

Shavuot celebration with Rabbi Herschel Schacter in the cinema barrack in Buchenwald, May 18, 1945. Photo: Charles W. Herr (National Archives at College Park, Maryland) The majority of the 904 minors who were counted among the survivors of the camp in mid-April 1945 were older than 15 years. The few children among them survived through the solidarity of political prisoners. The youngest, four-year-old Janek Szlajfstajn and Stefan Jerzy Zweig, were hidden in the prisoner infirmary and in the small camp; Soviet prisoners hid 11-year-old Menek Schiller in Block 30; his two-year-old brother survived with other children under the protection of the Jewish prisoners in Block 23; 6-year-old Isaak Goldblum was accommodated in “Children's Block 66” in the Small Camp and 7-year-old Israel Lau in “Children's Block 8”.

Janek Szlajfstajn, the youngest survivor of Buchenwald, before leaving for Switzerland, June 19, 1945. Photo: George A. Haynia (National Archives at College Park, Maryland) Most of the Jewish youth in Buchenwald were orphans without a home. The Schiller brothers found their mother in the former Meuselwitz subcamp. Individuals joined their national group trips home. The 17-year-old Leopold Huppert drove to Prague with the liberated Czechs in May 1945. He and other young people from Theresienstadt, Dachau and Buchenwald were accepted at Štiřín Castle. There was one of the rest homes that the pedagogue Přemysl Pitter had opened to take in orphaned Jewish youths in vacant castles.

Departure of the train for France from Buchenwald station, June 5, 1945. Photo: James E. Myers (National Archives at College Park, Maryland) On June 5, 1945, the first passenger train with Jewish youth and children left Weimar station. 427 young people - boys from Buchenwald and girls from Bergen-Belsen - drove to the French town of Écouis, where they were warmly welcomed. They should recover, connect with loved ones and decide on their future path. In addition to France and Switzerland, Great Britain also took in hundreds of young Jews in the summer of that year.

Before leaving for France, June 5, 1945. (Willy Fogel; Buchenwald Memorial) "Vo are our parents? ir Nazi murderers… ”wrote 15-year-old Josek Dziubak, one of the boys from Block 66, in chalk on one of the trains to France. It took him two years to find relatives who brought him to the United States. Another member of the group, Robert Wajcman, said of the photo many years later: “Joe really spoke for us all. We had all just begun to understand how few of our family members were still alive. "

Children in Block 66

- Jacques Ribons / Jakob Rybsztajn (M / Poland, 1927)

- Henry Kinast (M / 1929)

- Bernard Ribons / Berek Rybsztajn (M / Poland, 1929-2011)

Naftali Fürst, Pavel Kohn, Israel-Laszlo Lazar and Alex Moskovic

Other prisoners of Block 66

- Frank Dobia (b.1926)

Children in Block 8

- Elie Buzyn (M / Poland, 1929)

- Zoltan Blau (M / Hungary, 1930)

- Abe Chapnick (M / Poland, 1930-2016)

- Romek Wajsman / Robbie Waisman (M / Poland, 1931)

- Yisrael Meir Lau (M / Poland, 1937)

Child survivors

- Israel Laszlo Lazar (Romania, 1930) -- arrived on Feb 6, 1945 (15 yo)

- Pavel Kohn (Czechia, 1929-2017) -- Feb 10, 1945 (15)

- Alex Moskovic (Slovakia, 1931-2019) - Jan 26, 1945 (13)

- Naftali Furst (Slovakia, 1933) -- Jan 23, 1945 (12)

Non-identified children

Zysio Abramovicz, <Abram Czapnik>, Albert Dymant, Joseph Fachler, Léon Frydman, Moritz Freilich, Idek Goldmann, Lejzor Grunberg, Israel Grojsman, Jakob Kapelusz, Mayer Kilsztok, Léon Lewkowicz and Hersch Unger.

<Abram Chapnik>, Henri and Albert Dymant, Jozef Dziubak, <Salek Finkelstein>, <Wolf Fojgel>, Idel Goldblum, Jochan Goldkrantz, <Jakob Kapelusz>, Nachman Klugmann, Max Kozuch, Manfred Lewin, <Theodore Lowy>, Szymk Michalowicz, Hans Oster, Salek Rotschild, Salek Sandowski, Abram Schilcott, Jozef Schwarczberg, Moniek Solarz, Hersch Unger, Usher, Ivar Segalowitz, Moishe Shapiro, <Romek Wajsman> and Lolek Weinstein

- Joe Majer = Salomon Majer

- Philip Kanner = Fajwen Kaner

- Jerry Kapelus = Jakob Kapelusz

- Ted "Booby" Lowy (Lewy) = Theodor Lowy

- Eddy Balter = Elias Balter

- Willy Fogel = Wolf Vogel / Wolf Fojgel

- Max Kosuch

- Robbie Waisman = Romek Wajsman

- Leon Friedman

- Szaja Chaskiel

Nathan Swarc, <Romek Wajsman>, Leon Friedman, Hershel Ungar (Unger), Jakob Kapelusz, Beniek Mrowka

Abram Gzapnik, Herchel Unger, Joseph Fachler, Marek Lozinski, Heersh Linger

Yossl Baker, Henry Salter

Kuba Enoch, George Grojnowski and Jack Meister (see YouTube)

External links

Pages in category "Buchenwald (subject)"

The following 119 pages are in this category, out of 119 total.

1

- Rudi Dingfelder / Robert Felder (M / Germany, 1924-1986), Holocaust survivor

- Milo Adoner (M / France, 1925-2020), Holocaust survivor

- Chaim Aizen

- Gabriel Birkenwald (M / Belgium, 1926), Holocaust survivor

- Jehoszua Cygelfarb

- Arnost Lustig (M / Czechia, 1926-2011), Holocaust survivor

- Herschel Wajchendler / Harry Wajchendler (M / Poland, 1926-2005), Holocaust survivor

- Simcha Applebaum (M / Belarus, 1927), Holocaust survivor

- Bill Basch

- Shaul Bekierman

- Moniek Bergermann / Monty Bergerman (M / Poland, 1927-2010), Holocaust survivor

- Henri Borlant (M / France, 1927), Holocaust survivor

- Sabatino Finzi (M / Italy, 1927), Holocaust survivor

- Jack Gruener

- Menachem Haberman

- Mendel Herskovitz (M / Poland, 1927), Holocaust survivor

- Wolf Himmelfarb / William Himmelfarb (M / Poland, 1927-2003), Holocaust survivor

- Harry Olmer / Chaim Olmer (M / Poland, 1927), Holocaust survivor

- Jakob Rybsztajn / Jacques Ribons (M / Poland, 1927-2016), Holocaust survivor

- Leon Rytz (M / Poland, 1927), Holocaust survivor

- Zwi Steinitz (M / Poland, 1927), Holocaust survivor

- Léon Zyguel (M / France, 1927-2015), Holocaust survivor

- Jacob Ajzenberg / Jack Ajzenberg (M / Poland, 1928), Holocaust survivor

- Icek Alterman

- Shlomo Binke / Sam Binke (M / Poland, 1928-1998), Holocaust survivor

- Majer Bomstyk / Mayer Bomsztek (M / Poland, 1928), Holocaust survivor

- Chiel Brauner / Henry Brown (M / Poland, 1928-2011), Holocaust survivor

- Enzo Camerino (M / Italy, 1928), Holocaust survivor

- Zelig Ellenbogen

- David Faber (M / Poland, 1928-2015), Holocaust survivor

- Wolf Fojgel / Willy Fogel (M / Poland, 1928-2003), Holocaust survivor

- Jonah Fuks / John Fox (M / Poland, 1928), Holocaust survivor

- Martin Greenfield / Maxmilian Grunfeld (M / Slovakia, 1928), Holocaust survivor

- Arek Herszlikowicz / Arek Hersh (M / Poland, 1928), Holocaust survivor

- Hans Oster / Henry Oster (M / Germany, 1928-2019), Holocaust survivor

- Franco Schoenheit (M / Italy, 1927), Holocaust survivor

- Gilberto Salmoni (M / Italy, 1928), Holocaust survivor

- Salek Sandowski (M / Poland, 1928), Holocaust survivor

- Ignatz Spett

- Tom Szelenyi (M / Hungary, 1928-2015), Holocaust survivor

- Israel Unikowski (M / Poland, 1928), Holocaust survivor

- Chaim Wajchendler / Howard Chandler (M / Poland, 1928), Holocaust survivor

- Felix Weinberg (M / Czechia, 1928-2012), Holocaust survivor

- Stanley Weinstein (M / Poland, 1928), Holocaust survivor

- Elie Wiesel (M / Romania, 1928-2016), Holocaust survivor

- Binem Wrzonski (M / Poland, 1928), Holocaust survivor

- Zysio Abramovicz (M / Poland, 1929), Holocaust survivor

- Marton Adler

- Sandor Adler (M / Romania, 1929), Holocaust survivor

- Herech Balsam / Harry Balsam (M / Poland, 1929), Holocaust survivor

- Jacob Banach / Jack Bennett (M / Poland, 1929-1988), Holocaust survivor

- Hersch Bergmann / Harry Bergmann (M / Poland, 1929), Holocaust survivor

- Szyja Berliner (M / Poland, 1929), Holocaust survivor

- Fishel Blumsztajn / Fiszel Blumenstajn (M / Poland, 1929), Holocaust survivor

- Hersch Brand / Zvi Brand (M / Poland, 1929), Holocaust survivor

- Aaron Bulwa / Armand Bulwa (M / Poland, 1929), Holocaust survivor

- Elie Buzyn (M / Poland, 1929), Holocaust survivor

- Yehoshua Robert Büchler (Slovakia, 1929-2009), Holocaust survivor

- Joseph Fachler (M / Poland, 1929), Holocaust survivor

- Chaim Finkelstajn / Charles Finkel (M / Poland, 1929), Holocaust survivor

- Thomas Geve / Stefan Cohn (M / Germany, 1929), Holocaust survivor

- Idel Goldblum / George Goldbloom (M / Poland, 1929-2005), Holocaust survivor

- Idek Goldmann

- Ben Helfgott (M / Poland, 1929), Holocaust survivor

- Samuel Hoffman / Martin Hoffman (M / Czechia, 1929-2018), Holocaust survivor

- Kalman Kaliksztajn / Kalman Kalikstein (M / Poland, 1929-1987), Holocaust survivor

- Jakob Kapelusz / Jerry Kapelus (M / Poland, 1929), Holocaust survivor

- Imre Kertész (M / Hungary, 1929-2016), Holocaust survivor

- Henry Kinast (M / Poland, 1929-2019), Holocaust survivor

- Pavel Kohn (M / Czechia, 1929-2017), Holocaust survivor

- Kurt Kotouč

- Paul Molnar (M / Hungary, 1929-2009), Holocaust survivor

- Berek Rybsztajn / Bernard Ribons (M / Poland, 1929-2011), Holocaust survivor

- Karl Heinz Rosner (M / Germany, 1929), Holocaust survivor

- Irving Roth (Slovakia, 1929)

- Yehuda Shmuelli (M / Slovakia, 1929), Holocaust survivor

- Perry Shulman (M / Poland, 1929-2015), Holocaust survivor

- Chaim Spiro

- Zvi Herschel Unger (M / Poland, 1929), Holocaust survivor

- Julek Zylberger

- William Auspitz (M / Hungary, 1930), Holocaust survivor

- Zoltan Blau

- David Borgenicht

- Abram Czapnik / Abe Chapnick (M / Poland, 1930-2016), Holocaust survivor

- Ralph Codikow

- Lewin Frydmann / Léon Frydman (M / Poland, 1930), Holocaust survivor

- Chaim Fuks / Harry Fox (M / Poland, 1930), Holocaust survivor

- Moniek Gruenstein

- Bertrand Herz (France, 1930)

- Léon Lewkowicz (M / Poland, 1930), Holocaust survivor

- Sol Lurie

- Josef Perl (M / Slovakia, 1930), Holocaust survivor

- Ivar Segalowitz (M / Lithuania, 1930), Holocaust survivor

- Joseph Szwarcberg / Jozef Schwarczberg (M / Poland, 1930), Holocaust survivor

- Moniek Baumel / Martin Baumel (M / Poland, 1931), Holocaust survivor

- Moshe Ben-Ozer

- Salek Finkelstein (M / Poland, 1931), Holocaust survivor

- Sevek Finkelstein / Sidney Finkel (M / Poland, 1931), Holocaust survivor

- Heniek Kaliksztajn / Hyman Kalikstein (M / Poland / 1931), Holocaust survivor

- Moshe Kravitz / Moshe Kravec (M / Lithuania, 1931), Holocaust survivor

- Alex Moskovic (M / Slovakia, 1931-2019), Holocaust survivor

- Romek Wajsman / Robbie Waisman (M / Poland, 1931), Holocaust survivor

- Jakub Finkelstajn / Jacques Finkel (M / Poland, 1932), Holocaust survivor

- Pinchas Gutter (M / Poland, 1932), Holocaust survivor

- Beniek Mrowka (M / Poland, 1932), Holocaust survivor

- Simon Saks

- Henri Rozen-Rechels (Poland, 1933)

- Martin Schiller (M / Poland, 1933), Holocaust survivor

- Berek Goldberg

- Michael Urich

- Coby Lubliner

- Izio Rosenman (M / Poland, 1935), Holocaust survivor

- Yisrael Meir Lau (M / Poland, 1937), Holocaust survivor

- David Perlmutter (M / Poland, 1937), Holocaust survivor

- Isaak Goldblum (M / Poland, 1939), Holocaust survivor

- Stefan Jakubowicz / Stephen Jacobs (M / Poland, 1939), Holocaust survivor

- Joseph Schleifstein (M / Poland, 1941), Holocaust survivor

- Stefan Jerzy Zweig (M / Poland, 1941), Holocaust survivor

- Julius Maslovat / Yidele Henechowicz (M / Poland, 1942), Holocaust survivor

Media in category "Buchenwald (subject)"

The following 19 files are in this category, out of 19 total.

- 1958 Apitz.jpg 247 × 400; 51 KB

- 1958 Wiesel.jpg 894 × 1,400; 205 KB

- 1960 Leopold film.jpg 213 × 300; 14 KB

- 1960 Wiesel.jpg 246 × 403; 29 KB

- 1963 Beyer film.jpg 206 × 305; 26 KB

- 1976 Lustig.jpg 301 × 499; 25 KB

- 1980 Wiesel it.jpg 294 × 500; 11 KB

- 1984 Hemmendinger fr.jpg 345 × 499; 40 KB

- 1996 Werber.jpg 308 × 499; 41 KB

- 2000 Hemmendinger Krell en.jpg 348 × 499; 33 KB

- 2000 Hemmendinger.jpg 399 × 576; 42 KB

- 2002 Mehler (doc).jpg 1,920 × 2,560; 296 KB

- 2011 Lau.jpg 333 × 499; 26 KB

- 2012 Cohen (doc).jpg 182 × 268; 8 KB

- 2013 Weinberg.jpg 346 × 499; 44 KB

- 2015 Kadelbach film.png 259 × 367; 162 KB

- 2017 Gutter.jpg 333 × 499; 17 KB

- 2019 Perlmutter.jpg 346 × 499; 46 KB

- 2021 Wajsman.jpg 429 × 648; 216 KB