Romek Wajsman / Robbie Waisman (M / Poland, 1931), Holocaust survivor

Romek Wajsman / Robbie Waisman (M / Poland, 1931), Holocaust survivor.

- One of the youngest Holocaust survivor of Buchenwald, <Block 8>

- KEYWORDS : <Poland> <Skarzysko Ghetto> <Buchenwald> <Block 8> <Liberation of Buchenwald> / <Canadian Orphans>

- MEMOIRS : Boy from Buchenwald (2021) -- The Buchenwald Children (2000), 52-63 -- see also Vancouver Holocaust Educational Center.

Biography

Romek Wajsman was born in Poland in 1931. He survived the Skarzysko ghetto, forced labor in a factory that made aircraft shells and digging anti-tank ditches before he ended up in Buchenwald. There, he was in a barrack with another boy of his age, Abe Chapnick (1930-2016), who became his closest friend. The political organization at Buchenwald was able to protect them and - as they discover only after liberation - many other children at the camp.

Liberation of Buchenwald

A picture shows him standing behind Stefan Jerzy Zweig and David Perlmutter at Buchenwald in the days immediately following the liberation of the camp (1945):

- Fotoarchiv Buchenwald -- Pictured from left to right are Romek Wajsman, Stefan Jerzy Zweig and David Perlmutter

Romek was one the youngest child Holocaust survivors at Buchenwald:

- USHMM Collections -- Among those pictured are first row (left to right): Lolek Blum, David Perlmutter, Birenbaum, Stefan Jerzy Zweig, Joseph Schleifstein, and Yisrael Meir Lau (middle row, far right). Middle row: Nathan Szwarc, Jack Neeman, Berek Silber, Jakub Finkelstajn (Jacques Finkel), unidentified, Marek Milstein, and Salek Finkelstein. Back row: Elek Grinbaum [or Grinberg], Chaim Finkelstajn (Charles Finkel), Romek Wajsman (Wekselman), and Abe Chapnick. The boys are dressed in outfits made from German uniforms due to a clothing shortage.

OSE Orphanage, France

Romek was among the 426 Buchenwald children sent to France at the OSE orphanage. His tutor there was Manfred Reingewitz.

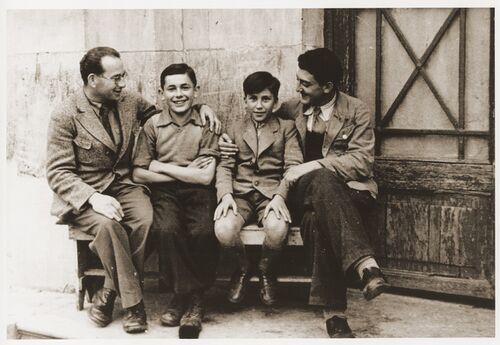

- USHMM Collection -- Pictured from left to right are Manfred Reingewitz, Romek Wajsman, Salek Finkelstein, and Ralph Lewin (OSE Orphanage, 1946)

- USHMM Collection -- Romek Wajsman is again pictured sitting next to his advisor Manfred Reingewitz, while Salek Finkelstein is on the shoulders of Ralph Lewen.

- USHMM Collection -- Group portrait portrait of Jewish children against a backdrop of the Eiffel Tower. The children are residents of the Le Vésinet children's home, sponsored by the OSE (Oeuvre de secours aux Enfants). Pictured in the front from left to right are Joseph Fachler, Abe Chapnick and Herchel Unger. In the middle row are Leon Friedman, Salek Sandowski and Romek Wajsman. Standing behind is Marek Lozinski (b. Lodz, 1927).

After the Holocaust

Romek and his sister Leah were the only members of the family to survive the Holocaust. Leah married and moved to Israel. Romek instead was among the orphans who in 1948 were taken by the Canadian Jewish Congress to live there. He became Bobbie Waisman and a successful businessman in Vancouver. After decades of silence, he began to talk publicly about his experience, in schools, churches and community centers. In 2020 he was honored the Caring Canadian Award.

Book : "Boy from Buchenwald" (2021)

It was 1945 and Romek Wajsman had just been liberated from Buchenwald, a brutal concentration camp where more than 60,000 people were killed. He was starving, tortured, and had no idea where his family was-let alone if they were alive. Along with 472 other boys, including Elie Wiesel, these teens were dubbed "The Buchenwald Boys." They were angry at the world for their abuse, and turned to violence: stealing, fighting, and struggling for power. Everything changed for Romek and the other boys when Albert Einstein and Rabbi Herschel Schacter brought them to a home for rehabilitation. Romek Wajsman, now Robbie Waisman, humanitarian and Canadian governor general award recipient, shares his remarkable story of transforming pain into resiliency and overcoming incredible loss to find incredible joy.

USHMM Profile

Robert Waisman (born Romek Wajsman) is the son of Rywka (Gil) and Chiel Wajsman. He was born on February 2, 1930 in Skarzysko, Poland, where his father worked as a tailor. Romek had five older siblings, Chaim, Mottel, Moishe, Abram and Lea. The Wajsman family was forced into the local ghetto in the fall of 1941. Romek's older brothers were sent to work in the HASAG factory camp in Skarzysko. Chaim obtained information about the planned liquidation of the Skarzysko ghetto shortly before it was to occur. In the early morning hours of the appointed day, Chaim entered the ghetto and smuggled Romek out in the back of a truck. Chaim managed to obtain a permit for Romek to work with his brothers at the HASAG plant, marking aircraft shells with the factory's initials. With the advance of the Red Army in the summer of 1944, the HASAG camp was closed, and Romek was sent to dig anti-tank ditches in Przedborz. Subsequently, he was transfered to the HASAG camp in Czestochowa. He remained there for several months, before being sent to Buchenwald. Romek was liberated in Buchenwald on April 11, 1945. Shortly afterwards, representatives of the OSE (Oeuvre de Secours aux Enfants) came to the camp and arranged for the transport of 430 Jewish children, Romek among them, to an OSE children's home in Ecouis, France. Romek was transferred from Ecouis to the OSE home at Le Vesinet, near Paris. In 1948 he and twenty other OSE children immigrated to Canada with the help of the Canadian Jewish Congress. Romek and his sister, Lea, were the only members of the family to survive the war.

Virtual Museum, Canada

- I. Skarszysko, Poland

I was born in 1931 in Skarszysko, Poland, a very tight-knit community. I was the youngest of six children, with four older brothers and one sister. My father was a tailor and my mother looked after us all. There was a lot of love in our family. As the baby in the family, I was very pampered and felt that everything revolved around me. My parents were religious. I remember the Sabbath as a very special time, when my father would tell us Sholom Aleichem stories, like "Fiddler on the Roof." My only regret is that I do not have any photographs of my family. I am always envious of people who have pictures of their parents.

My first experience with anti-Semitism occurred when I was 6 years old. My two best friends were a brother and sister, Wiesiek and Halinka. We were inseparable. We had sleepovers at each other's homes. I remember how delighted I was to help decorate their Christmas tree. They, in turn, loved the special food my mother cooked at Rosh Hashanah (Jewish new year). That all changed just before the Easter break. I was on my way home from school when, suddenly, a group of children cornered me and started beating me up. With every punch and kick I heard them say, "This is for the murder of our Lord Jesus Christ." Wiesiek and Halinka, my very best friends, led the attack. I remember how angry I felt on the way home from the hospital. I kept asking my parents, "Why?" I lost a wonderful friendship that day. I lost my innocence, and life was never the same after that.

After Hitler's rise to power, I remember my parents' discussions. They were frightened and could not believe the situation that was developing around us. After Kristallnacht, German-Jews started coming into Poland. They came to our house to ask my father for advice, to talk things over. They expressed their fears, but my father believed that Germany was the epitome of civilization and was not capable of atrocities.

- II. During the Holocaust

I was eight years old in 1939 when my city was bombed and occupied by the Nazis. I thought that it was a game until I saw a man shot to death. I matured forty years in that instant.

Then the round-ups started. Soldiers with bayonets and guns would push Jews onto trucks. Some of the Jews came back after the day's work, some didn't. At the next round-up, some people started to run away. People were getting frantic.

Hasag, a German ammunitions factory was established in our town and the Jews were forced to work there. My father had to close his tailor shop and work in the munitions factory, along with my sister and brothers.

In 1940, the ghetto was formed in Skarszysko and my parents sent me to stay with a non-Jewish family on a farm. I ran away after about a month. I had to walk for hours. When I got back to Skarszysko, I had to smuggle myself into the ghetto through a hole in the wall. When I arrived, my mother hugged me and kissed me but my father took off his belt and spanked me. That was the first and last spanking I ever had.

Running away from the farm that day saved my life. Shortly afterwards the SS proclaimed that anyone harbouring a Jewish child should give up the child to the police in return for a sack of flour or sugar. I know that many children survived in hiding elsewhere, but in Skarszysko, to my knowledge, none did. They were all denounced.

In 1941, my eldest brother, Chaim heard that the ghetto was going to be liquidated. That night he smuggled me out. I kissed my mother goodbye. The next day, everyone in the ghetto was sent to Treblinka and gassed. My mother was among them.

Chaim had a privileged job of driving a truck in and out of the ghetto. He drove me to an abandoned farm and hid me in a haystack in an abandoned barn and told me that he would come back for me. I waited two days, then three days, and I became very worried. Finally, he came back and smuggled me into the work camp where my father and brother Abram were working. My job was to stamp ammunition shells with the initials 'FES'. I was very fast and I had no problem doing 3,200 shells a day.

In the mornings, when we lined up to be counted, Abram would pinch my cheeks to make me look healthier. At the end of the shift, we slept in barracks. There were no mattresses, just some straw. We slept in our clothes; we couldn't change. The lice were horrendous. Typhoid fever broke out and Abram came down with it.

There were no medications to give him. We just hid him and gave him water. If you asked for medical attention, they'd take you and shoot you. I looked after him during the day, and my father would look after him at night. One day, he was discovered and they took him away and shot him. My father was never the same after this. His black hair turned grey.

At this point my father and I were separated and I contracted typhoid fever. I didn't think I'd make it. I was alone, but somebody kept me alive. Somebody covered me with straw and gave me water. I tried to go back to work but I was weak and I stumbled. As the SS were taking me away to be shot, I was saved by an SS man who knew me. I slowly regained my health and went back to work.

I met Abe Chapnick, a boy a year older than me, and we remained together for the rest of the war. In 1944, when I was 13, Abe and I were sent to Buchenwald Concentration Camp (Map) and placed in Block 8 with Polish, French and German political prisoners. These prisoners helped protect us. There were very few Jews. My life in Buchenwald was actually easier than in the other camps. The political prisoners hid us during the day while they went to work. Sometimes we even received care parcels from the Red Cross. Once we found ourselves with a piece of chocolate. We weren't even sure what it was at first.

- III. Rediscovering Freedom

I was fourteen years old when I was liberated from Buchenwald on April 11, 1945. Suddenly a hush came over the camp and the shelling stopped. Our barrack was close to the main gate and I saw soldiers in different uniforms entering the camp. Prisoners came running out from everywhere. I ran out after a jeep and I saw some black American soldiers. I went up to one of them and I touched him. His name was Leon Bass. Years later, in 1983, I saw a picture of Leon in a magazine and tracked him down. We were reunited and have remained friends ever since.

Among the camp inmates there were leaders who gathered up all the children and began to take charge of us. I had no idea that there were 430 children scattered throughout Buchenwald. I had thought that Abe and I were the only children there. We were taken to live in the former SS barracks. We each had a bed and clean sheets. I remember being examined by many doctors and nurses and the Red Cross taking down our stories.

My immediate concern was to be reunited with my family. At that time I was not yet aware of the enormity of the Holocaust. The human mind doesn't accept some of these things. I knew that my brother, Abram, had died and I suspected my father was also dead, but I still hoped to find the rest of my family. I had no idea that Chaim was dead and that my mother had died in Treblinka. I found my sister Leah a few months later. She and I are the only survivors of our family.

We all wanted to go home, but we remained in Buchenwald for about three months because there was nowhere else to go. The authorities had a hard time convincing us that we could not go home and that our homes were no longer there. In my case, they explained how dangerous it would be to go to Poland, where returning Jews had been attacked. I could not understand why people, other than the Nazis, wanted to kill us. It took us a long time to understand our circumstances.

During the war, many of us had promised our elders that, should we survive, we would tell the world about what had happened. But when we were liberated, the memories were too terrible to deal with. It was too soon to speak. Besides, no one was interested.

A very powerful bond developed amongst the children. All we had was one another. Looking back, I realize what a blessing it was that we were together. They were my family. It took us a while to realize that we could go outside the gates of Buchenwald. At first we didn't dare to leave the camp, but then we started to go on little excursions around Buchenwald. We really savoured this new-found freedom.

I remember a journalist from Paris who visited us and then wrote an article titled "J'Accuse," accusing the world of indifference towards the 430 youngsters who had returned from hell and yet were still in a concentration camp. As a result of public pressure, the government of France agreed to admit the children of Buchenwald, even offering us French citizenship. And so we left for Ecouis, a town in northern France. I can still remember the relief of leaving Germany, as we crossed the border into France.

- IV. Orphanage

We were taken to a huge old mansion with dormitories, run by the OSE (Oeuvre de Secours aux Enfants). There, some of the Jewish children, including Elie Wiesel, demanded prayer books, services and kosher food. Although most of us had come from Orthodox homes before the war, many of us were reluctant to return to these practices. I had started to question God. Had he been on a leave of absence during the Holocaust? I was part of the group that broke away from religious observance.

As a group, we were headstrong, angry and unmanageable. They called us "les enfants terribles". We resisted going to classes and disrupted cultural events organized for us. Later, I had a chance to read some of the reports written about us at the time, which concluded that we had seen and suffered too much and could not be rehabilitated. They said that we were without redeeming value and likely to end up in jail as criminals. Obviously, the experts did not understand our trauma. As it turned out, none of us ended up in jail. Many of us became professionals, doctors, lawyers and businessmen. My friend Jezyk Zyskind became a well-known physicist. Another member of our group, Elie Wiesel, won the Nobel Prize for literature.

One day an expert was brought in to talk to us. When he came in, he took off his jacket and rolled up his sleeves. When we saw his Auschwitz number, there was a complete hush. I think our silence shocked him a little. He looked at us and finally he said "mein tiere kinder" (Yiddish for "my dear children"), and started to cry. That was the first time I openly shed a tear. I cried for the first time in five years. It was a very emotional time for me.

After that, things changed. From then on I suddenly understood that this was my life and I had to make something of it. My tough attitude was broken. Eventually, a group of about eighty of us was taken to Vesinet, a town outside of Paris, where we attended a regular school. I remained there for about three years and graduated high school. I worked very hard at school — I had so much catching up to do.

During this period a prominent Jewish couple, Jean and Jane Meyer, came to our school and offered to adopt me. They introduced me to the opera and theatre. But I felt very strongly about not giving up my name and I think that I had already decided to turn my back on Europe. The memories were too strong and painful. They were devastated when I applied to Canada for a visa. We remained close until they died and I am still in close contact with their children.

- V. Finding a Home

I remember being told that no country in the world, except Palestine, wanted us. Nearly all of the orphans put their names on the list for Palestine, but getting into Palestine was made nearly impossible at the time by the British blockade. The two other options open to us were Canada or Australia. Australia was attractive to many of us because it was so far from Europe.

Getting into Canada was tough. The process was a very lengthy one and you had to be absolutely healthy. Wearing glasses was enough to disqualify you. I had trouble getting approval because of my very low blood pressure. I had repeated blood tests and had all but given up hope when I finally got a letter accepting me into Canada.

I thought of Canada as a young country full of wheat fields. It seemed to be a place where I would never run out of bread. Canada represented a new life and a new beginning. Although I was anxious about the unknown, I remember feeling a tremendous amount of anticipation and excitement.

- VI. Coming to Canada

The voyage took about a week, which seemed quite long to me at the time. I have fond memories of the trip and remember reading Margaret Mitchell's Gone with the Wind in French.

I was seventeen when we landed in Halifax on December, 1948. I was disappointed to learn that I was not going to Montreal, as I spoke French. I wasn't told that I was going to Calgary until I was already on the train.

On the trip west, I couldn't get over the immense space and the sparse settlements along the way. You could see forever. As I crossed Canada by train, it occurred to me that so many people could have been saved in this vast country. So much land and yet there had been no room for Jewish refugees during the war.

We were accompanied by Roweena Pearlman, a Canadian Jewish Congress volunteer who was just a wonderful lady with a heart of gold. I think she used psychology on me by telling me how wonderful the Jewish community was in Calgary. She suggested that I stop over in Calgary for just a few days to meet her family. To please her, I stopped over for two days and stayed nine years.

Calgary seemed so new and so friendly. I was astounded to learn that I did not need a passport or ID card to get around every day. I thought I needed a visa to travel to another province but was told that all I needed was a driver's licence. I paid one dollar and got my first Canadian driver's licence.

My first night in Calgary I stayed with Roweena Pearlman's brother-in-law. I was so anxious to earn a living that the very next day I went to work at Smithbuilt Hats. That evening I went to live with Harry and Rachel Goresht and their children, Ida and Sam. To this day, they remain my family.

- VII. Becoming Canadian

The Jewish community really opened their hearts to us. The orphans always had a standing invitation to all the simchas (celebrations), weddings and bar mitzvahs.

I had always wanted to be an electrical engineer. My mechanical and electrical aptitude had helped save me during the Holocaust. As a forced labourer in a munitions factory, it had been my job to monitor ten machines and repair them when they broke down.

Instead, I went to night school and got a diploma in accounting because it was a quick way to get a job. I desperately wanted to be on my own and independent. In 1952, I brought my sister and her family over from Israel. By then it seemed too late to go back to school to study electrical engineering.

I worked for Sam and Lena Hanen in their store. When I got my accounting diploma, I worked in the office. They were good years and I learned a lot from Lena.

In 1959 I married Gloria Lyons and we moved to Saskatoon and had two kids, a son Howard and a daughter Arlaina. I started a children's wear store, which eventually became three stores. I became very involved in the Jewish community. I was president of the Jewish community in Saskatoon and president of B'nai Brith. In 1978 we moved to Vancouver where I worked in the hotel business.

I think this is the greatest country in the world. I have had nothing but wonderful experiences since coming to Canada. When I speak to young people about my experiences during the Holocaust, I always ask them to keep an open mind when they see and meet newcomers to this country. I ask them to experience the adventure of getting to know other kinds of people. Each one of us possesses unique and wonderful qualities, regardless of colour or religion.

OSE Orphanage List

- #375 Romek Wajsman, Poland, <1930>