Difference between revisions of "Category:Historical Jesus Studies"

| Line 58: | Line 58: | ||

[[File:Bart D. Ehrman.jpg|thumb|150px|[[Bart D. Ehrman]]]] | [[File:Bart D. Ehrman.jpg|thumb|150px|[[Bart D. Ehrman]]]] | ||

* See [[Historical Jesus Studies 1400s]] & [[Historical Jesus Studies 1500s]] | * See [[:Category:Historical Jesus Studies--1400s|Historical Jesus Studies 1400s]] & [[:Category:Historical Jesus Studies--1500s|Historical Jesus Studies 1500s]] | ||

The earliest Lives of Jesus of the Renaissance were theological or poetical harmonies of the four Gospels, authored by humanists like [[Antonio Cornazzano]] and [[Pietro Aretino]]. A more critical approach emerged with the Reformation. [[Martin Luther]] discussed the Jewishness of Jesus and by the end of the 16th century the work of [[Bartolomeo Dionigi]] located the life of Jesus within Jewish history. | The earliest Lives of Jesus of the Renaissance were theological or poetical harmonies of the four Gospels, authored by humanists like [[Antonio Cornazzano]] and [[Pietro Aretino]]. A more critical approach emerged with the Reformation. [[Martin Luther]] discussed the Jewishness of Jesus and by the end of the 16th century the work of [[Bartolomeo Dionigi]] located the life of Jesus within Jewish history. | ||

* See [[Historical Jesus Studies 1600s]] | * See [[:Category:Historical Jesus Studies--1600s|Historical Jesus Studies 1600s]] | ||

At the beginning of the 17th century the tale of the "Wandering Jew" spread into Europe. The anti-Semitic implications of the myth of the impious Jew cursed by Jesus and condemned to wander until the end of time would greatly affect even the scholarly and fictional narratives of the life of Jesus based on canonical sources. | At the beginning of the 17th century the tale of the "Wandering Jew" spread into Europe. The anti-Semitic implications of the myth of the impious Jew cursed by Jesus and condemned to wander until the end of time would greatly affect even the scholarly and fictional narratives of the life of Jesus based on canonical sources. | ||

| Line 70: | Line 70: | ||

Fictional works were popular representations of the events surrounding the birth and passion of Christ. | Fictional works were popular representations of the events surrounding the birth and passion of Christ. | ||

* See [[Historical Jesus Studies 1700s]] | * See [[:Category:Historical Jesus Studies--1700s|Historical Jesus Studies 1700s]] | ||

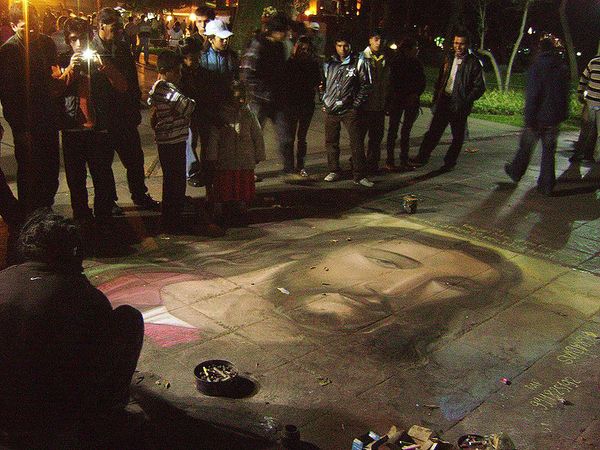

Jesus remained an important subject in the arts, as attested especially by the production of numerous oratorios, including Bach's Matthäuspassion, Haendel's Messiah, and the many based on Metastasio's libretto, The Passion of Jesus Christ. In 1768 Scottish preacher [[John Cameron]] published what is regarded as the first modern novel on Jesus | Jesus remained an important subject in the arts, as attested especially by the production of numerous oratorios, including Bach's Matthäuspassion, Haendel's Messiah, and the many based on Metastasio's libretto, The Passion of Jesus Christ. In 1768 Scottish preacher [[John Cameron]] published what is regarded as the first modern novel on Jesus | ||

| Line 78: | Line 78: | ||

The unpublished work of [[Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel]] in 1795 shows how in light of Emanuel Kant's thought Jesus had become to be interpreted in German philosophical circles as a teacher of a morality founded on reason. | The unpublished work of [[Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel]] in 1795 shows how in light of Emanuel Kant's thought Jesus had become to be interpreted in German philosophical circles as a teacher of a morality founded on reason. | ||

* See [[Historical Jesus Studies 1800s]] | * See [[:Category:Historical Jesus Studies--1800s|Historical Jesus Studies 1800s]] | ||

At the beginning of the 19th century the first critical approaches to the Life of Jesus were characterized by the attempt either to "eliminate" the supernatural elements in the Gospel narratives (Jefferson) or to "explain" them in rationalistic terms (Paulus). The breakthrough came with the work of [[David Friedrich Strauss]] (1835) who showed that the Gospel narratives ought not to be taken as "objective" reports but as "mythological" retelling of historical events. Strauss defined what would become the "scholarly" approach; the success of his work marked the beginning of contemporary research on the Historical Jesus. The Emancipation of the Jews in Western Europe led to the emergence of Jewish scholarship and [[Joseph Salvador]] was in 1838 the first Jewish scholar to deal with the historical Jesus. | At the beginning of the 19th century the first critical approaches to the Life of Jesus were characterized by the attempt either to "eliminate" the supernatural elements in the Gospel narratives (Jefferson) or to "explain" them in rationalistic terms (Paulus). The breakthrough came with the work of [[David Friedrich Strauss]] (1835) who showed that the Gospel narratives ought not to be taken as "objective" reports but as "mythological" retelling of historical events. Strauss defined what would become the "scholarly" approach; the success of his work marked the beginning of contemporary research on the Historical Jesus. The Emancipation of the Jews in Western Europe led to the emergence of Jewish scholarship and [[Joseph Salvador]] was in 1838 the first Jewish scholar to deal with the historical Jesus. | ||

* See [[Historical Jesus Studies 1850s]] | * See [[:Category:Historical Jesus Studies--1850s|Historical Jesus Studies 1850s]] | ||

[[Ernest Renan]]'s Life of Jesus had a sensational impact in mid-19th century. Based on the premise that Jesus’ life should be studied critically like that of every other man, Renan interpreted jesus as a teacher of morality, downplaying the apocalyptic and supernatural elements of Gospels narratives. | [[Ernest Renan]]'s Life of Jesus had a sensational impact in mid-19th century. Based on the premise that Jesus’ life should be studied critically like that of every other man, Renan interpreted jesus as a teacher of morality, downplaying the apocalyptic and supernatural elements of Gospels narratives. | ||

| Line 92: | Line 92: | ||

More conservative theologians, like [[Martin Kähler]], argued that the "real" Jesus was not the so-called "Historical Jesus" but the Christ proclaimed by the Christian faith. | More conservative theologians, like [[Martin Kähler]], argued that the "real" Jesus was not the so-called "Historical Jesus" but the Christ proclaimed by the Christian faith. | ||

* See [[Historical Jesus Studies 1900s]] | * See [[:Category:Historical Jesus Studies--1900s|Historical Jesus Studies 1900s]] | ||

* See [[Historical Jesus Studies 1910s]] | * See [[:Category:Historical Jesus Studies--1910s|Historical Jesus Studies 1910s]] | ||

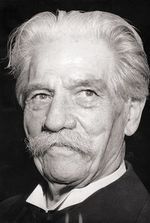

The work of [[Albert Schweitzer]] continued to dominate the scholarly debate, with the publication of the English tr. in 1910 and the second ed. in 1913. New voices enriched the international landscape. Jewish scholarship emerged in England with [[Claude G. Montefiore]], [[Gerald Friedlander]], and [[Israel Abrahams]]. Italian scholars also joined the debate with [[Baldassarre Labanca]], [[Felice Momigliano]], and [[Pietro Chiminelli]]. | The work of [[Albert Schweitzer]] continued to dominate the scholarly debate, with the publication of the English tr. in 1910 and the second ed. in 1913. New voices enriched the international landscape. Jewish scholarship emerged in England with [[Claude G. Montefiore]], [[Gerald Friedlander]], and [[Israel Abrahams]]. Italian scholars also joined the debate with [[Baldassarre Labanca]], [[Felice Momigliano]], and [[Pietro Chiminelli]]. | ||

| Line 101: | Line 101: | ||

The [[Jesus Survival Theory]] was revived in fictional ([[George Moore]]) and esoteric circles. | The [[Jesus Survival Theory]] was revived in fictional ([[George Moore]]) and esoteric circles. | ||

* See [[Historical Jesus Studies 1920s]] | * See [[:Category:Historical Jesus Studies--1920s|Historical Jesus Studies 1920s]] | ||

The 1920s were characterized by the success of some very popular fictional works on Jesus--[[La storia di Cristo (1921 Papini), novel]]; [[The King of Kings (1927 DeMille), film]], [[Jesus, the Son of Man (1928 Gibran), poetry]], and [[The Escaped Cock (1928 Lawrence), novel]]. There was now a global market that included authors of different countries, serving an international audience. | The 1920s were characterized by the success of some very popular fictional works on Jesus--[[La storia di Cristo (1921 Papini), novel]]; [[The King of Kings (1927 DeMille), film]], [[Jesus, the Son of Man (1928 Gibran), poetry]], and [[The Escaped Cock (1928 Lawrence), novel]]. There was now a global market that included authors of different countries, serving an international audience. | ||

| Line 109: | Line 109: | ||

In a long essay published in 1929 in the [[Harvard Theological Review]], [[Luigi Salvatorelli]] offered a most detailed survey of "The Historical Investigation of the Origins of Christianity ... from Locke to Reitzenstein." | In a long essay published in 1929 in the [[Harvard Theological Review]], [[Luigi Salvatorelli]] offered a most detailed survey of "The Historical Investigation of the Origins of Christianity ... from Locke to Reitzenstein." | ||

* See [[Historical Jesus Studies 1930s]] | * See [[:Category:Historical Jesus Studies--1930s|Historical Jesus Studies 1930s]] | ||

Rampant anti-Semitism and Christian theological skepticism about the Historical (Jewish) Jesus led to the decline of Jesus research in the 1930s. The burden of proving the relevance of the historical Jesus was left almost entirely on the shoulders of Jewish scholars and authors and of a few Christian scholars (mostly French and British), who struggled to keep alive the interest in the subject and in the close historical (and religious) relationship between Judaism and Christianity. | Rampant anti-Semitism and Christian theological skepticism about the Historical (Jewish) Jesus led to the decline of Jesus research in the 1930s. The burden of proving the relevance of the historical Jesus was left almost entirely on the shoulders of Jewish scholars and authors and of a few Christian scholars (mostly French and British), who struggled to keep alive the interest in the subject and in the close historical (and religious) relationship between Judaism and Christianity. | ||

* See [[Historical Jesus Studies 1940s]] | * See [[:Category:Historical Jesus Studies--1940s|Historical Jesus Studies 1940s]] | ||

As part of the "final solution," Nazi Germany sponsored at Jena the activities of the ''Institut zur Erforschung und Beseitigung des jüdischen Einflusses auf das deutsche kirchliche Leben / Institute for the Study and Eradication of Jewish Influence on German Religious Life'' (1939-1945), directed by respected German theologian [[Walter Grundmann]]. The notion of the "Aryan Jesus" was promoted in Nazi propaganda (notably, [[Der ewige Jude (The Eternal Jew / 1940 Hippler), arch-fi documentary]]), but was not foreign elsewhere, even in democratic Great Britain or America, where anti-Judaism (if not anti-Semitism) had also strong roots. | As part of the "final solution," Nazi Germany sponsored at Jena the activities of the ''Institut zur Erforschung und Beseitigung des jüdischen Einflusses auf das deutsche kirchliche Leben / Institute for the Study and Eradication of Jewish Influence on German Religious Life'' (1939-1945), directed by respected German theologian [[Walter Grundmann]]. The notion of the "Aryan Jesus" was promoted in Nazi propaganda (notably, [[Der ewige Jude (The Eternal Jew / 1940 Hippler), arch-fi documentary]]), but was not foreign elsewhere, even in democratic Great Britain or America, where anti-Judaism (if not anti-Semitism) had also strong roots. | ||

| Line 121: | Line 121: | ||

After the war, fiction regained its freedom to surprise and scandalize with [[King Jesus (1946 Graves), novel|King Jesus]] by [[Robert Graves]]. Scholarly activity resumed with the seminal work of [[Joachim Jeremias]] on the "lost" sayings of Jesus; see [[Unbekannte Jesusworte (Unknown Sayings of Jesus / 1948 Jeremias), book]]. It couldn't be, however, as if nothing had happened. French scholar [[Jules Isaac]] not only denounced the influence of Christian anti-Judaism on scholarly research but also exposed the direct responsibilities of the Christian teaching of contempt for the spread of Nazi anti-Semitism and the tragedy of the Holocaust; see [[Jésus et Israël (Jesus and Israel / 1948 Isaac), book]]. | After the war, fiction regained its freedom to surprise and scandalize with [[King Jesus (1946 Graves), novel|King Jesus]] by [[Robert Graves]]. Scholarly activity resumed with the seminal work of [[Joachim Jeremias]] on the "lost" sayings of Jesus; see [[Unbekannte Jesusworte (Unknown Sayings of Jesus / 1948 Jeremias), book]]. It couldn't be, however, as if nothing had happened. French scholar [[Jules Isaac]] not only denounced the influence of Christian anti-Judaism on scholarly research but also exposed the direct responsibilities of the Christian teaching of contempt for the spread of Nazi anti-Semitism and the tragedy of the Holocaust; see [[Jésus et Israël (Jesus and Israel / 1948 Isaac), book]]. | ||

*[[1950s | * See [[:Category:Historical Jesus Studies--1950s|Historical Jesus Studies 1950s]] | ||

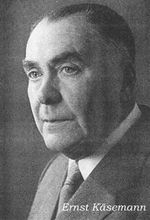

Time was ripe for a new beginning. The first step was to reissue the works of French scholars [[Maurice Goguel]] and [[Charles Guignebert]], which had been overlooked in the 1930s. | Time was ripe for a new beginning. The first step was to reissue the works of French scholars [[Maurice Goguel]] and [[Charles Guignebert]], which had been overlooked in the 1930s. | ||

| Line 131: | Line 131: | ||

By the end of the decade scholars were persuaded that a new Quest had started (see [[James M. Robinson]]). | By the end of the decade scholars were persuaded that a new Quest had started (see [[James M. Robinson]]). | ||

*[[1960s | * See [[:Category:Historical Jesus Studies--1960s|Historical Jesus Studies 1960s]] | ||

*[[1970s | * See [[:Category:Historical Jesus Studies--1970s|Historical Jesus Studies 1970s]] | ||

*[[1980s | * See [[:Category:Historical Jesus Studies--1980s|Historical Jesus Studies 1980s]] | ||

*[[1990s | * See [[:Category:Historical Jesus Studies--1990s|Historical Jesus Studies 1990s]] | ||

*[[2000s | * See [[:Category:Historical Jesus Studies--2000s|Historical Jesus Studies 2000s]] | ||

*[[2010s | * See [[:Category:Historical Jesus Studies--2010s|Historical Jesus Studies 2010s]] | ||

}} | }} | ||

Revision as of 07:52, 21 August 2015

|

Historical Jesus Studies -- History of research -- Overview The earliest Lives of Jesus of the Renaissance were theological or poetical harmonies of the four Gospels, authored by humanists like Antonio Cornazzano and Pietro Aretino. A more critical approach emerged with the Reformation. Martin Luther discussed the Jewishness of Jesus and by the end of the 16th century the work of Bartolomeo Dionigi located the life of Jesus within Jewish history. At the beginning of the 17th century the tale of the "Wandering Jew" spread into Europe. The anti-Semitic implications of the myth of the impious Jew cursed by Jesus and condemned to wander until the end of time would greatly affect even the scholarly and fictional narratives of the life of Jesus based on canonical sources. The most popular Lives of Jesus of the century were those authored by French Jesuit Bernardin de Montereul and Nicola Avancini, in 1637 and 1666 respectively. They were harmonies of the four gospels. Fictional works were popular representations of the events surrounding the birth and passion of Christ. Jesus remained an important subject in the arts, as attested especially by the production of numerous oratorios, including Bach's Matthäuspassion, Haendel's Messiah, and the many based on Metastasio's libretto, The Passion of Jesus Christ. In 1768 Scottish preacher John Cameron published what is regarded as the first modern novel on Jesus The Enlightenment brought about a more rationalistic approach to scriptures. The historical investigation of the origins of Christianity began with the British deists (John Locke, John Toland, Thomas Chubb, Thomas Morgan, Thomas Woolston, Peter Annet). By the end of the century the idea emerged that the gospels might not have told the "true" story of Jesus. Maybe Jesus was a Jewish religious leader (Voltaire) or a political revolutionary, whose failure prompted his reinterpretation as a religious figure (Hermann Samuel Reimarus), or maybe Jesus did not even exist and his biography was a completely mythological construct (Constantin-François Volney). The unpublished work of Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel in 1795 shows how in light of Emanuel Kant's thought Jesus had become to be interpreted in German philosophical circles as a teacher of a morality founded on reason. At the beginning of the 19th century the first critical approaches to the Life of Jesus were characterized by the attempt either to "eliminate" the supernatural elements in the Gospel narratives (Jefferson) or to "explain" them in rationalistic terms (Paulus). The breakthrough came with the work of David Friedrich Strauss (1835) who showed that the Gospel narratives ought not to be taken as "objective" reports but as "mythological" retelling of historical events. Strauss defined what would become the "scholarly" approach; the success of his work marked the beginning of contemporary research on the Historical Jesus. The Emancipation of the Jews in Western Europe led to the emergence of Jewish scholarship and Joseph Salvador was in 1838 the first Jewish scholar to deal with the historical Jesus. Ernest Renan's Life of Jesus had a sensational impact in mid-19th century. Based on the premise that Jesus’ life should be studied critically like that of every other man, Renan interpreted jesus as a teacher of morality, downplaying the apocalyptic and supernatural elements of Gospels narratives. The interest in Jesus' Jewish background was fostered by the scholarly work of Alfred Edersheim and by the extraordinary success of the novel Ben Hur by Wallace. Against the "Liberal Theology," Johannes Weiss argued that the proclamation of the Kingdom of God by Jesus should be interpreted in light of Jewish apocalypticism. More conservative theologians, like Martin Kähler, argued that the "real" Jesus was not the so-called "Historical Jesus" but the Christ proclaimed by the Christian faith. The work of Albert Schweitzer continued to dominate the scholarly debate, with the publication of the English tr. in 1910 and the second ed. in 1913. New voices enriched the international landscape. Jewish scholarship emerged in England with Claude G. Montefiore, Gerald Friedlander, and Israel Abrahams. Italian scholars also joined the debate with Baldassarre Labanca, Felice Momigliano, and Pietro Chiminelli. Movies began having a huge impact on the popular understanding of the figure of Jesus. Three films on Jesus (From the Manger to the Cross, Christus, and Intolerance) generated much interest and were influenced by the most recent developments in critical research, seeking "historical accuracy" in their "Oriental" settings and customs. The Jesus Survival Theory was revived in fictional (George Moore) and esoteric circles. The 1920s were characterized by the success of some very popular fictional works on Jesus--La storia di Cristo (1921 Papini), novel; The King of Kings (1927 DeMille), film, Jesus, the Son of Man (1928 Gibran), poetry, and The Escaped Cock (1928 Lawrence), novel. There was now a global market that included authors of different countries, serving an international audience. Among scholarly works, the most significant contribution was that offered by Joseph Klausner. His Life of Jesus, published in 1922 in Hebrew and translated in 1925 into English by Herbert Danby, was the first consistent attempt to reclaim Jesus from the perspective of the Jewish orthodox tradition. However, a general skepticism about the possibility and even the theological significance of the search for the Historical Jesus became dominant, supported by the authority of Rudolf Bultmann, who in his 1926 book on Jesus concluded that the only Jesus we can know is the risen Christ of the Christian faith. Besides his historical existence, virtually nothing can be recovered of the historical Jesus. The quest for the historical Jesus had therefore to be abandoned as both historically impossible and theologically superfluous. In a long essay published in 1929 in the Harvard Theological Review, Luigi Salvatorelli offered a most detailed survey of "The Historical Investigation of the Origins of Christianity ... from Locke to Reitzenstein." Rampant anti-Semitism and Christian theological skepticism about the Historical (Jewish) Jesus led to the decline of Jesus research in the 1930s. The burden of proving the relevance of the historical Jesus was left almost entirely on the shoulders of Jewish scholars and authors and of a few Christian scholars (mostly French and British), who struggled to keep alive the interest in the subject and in the close historical (and religious) relationship between Judaism and Christianity. As part of the "final solution," Nazi Germany sponsored at Jena the activities of the Institut zur Erforschung und Beseitigung des jüdischen Einflusses auf das deutsche kirchliche Leben / Institute for the Study and Eradication of Jewish Influence on German Religious Life (1939-1945), directed by respected German theologian Walter Grundmann. The notion of the "Aryan Jesus" was promoted in Nazi propaganda (notably, Der ewige Jude (The Eternal Jew / 1940 Hippler), arch-fi documentary), but was not foreign elsewhere, even in democratic Great Britain or America, where anti-Judaism (if not anti-Semitism) had also strong roots. In difficult wartimes, religious retelling of the life of Jesus offered some consolation and hope to suffering (Christian) people on both sides. The Life of Jesus by Catholic priest Giuseppe Ricciotti in Italy and the radio-play The Man Born to Be King by playwright Dorothy L. Sayers in England played such role in those years. After the war, fiction regained its freedom to surprise and scandalize with King Jesus by Robert Graves. Scholarly activity resumed with the seminal work of Joachim Jeremias on the "lost" sayings of Jesus; see Unbekannte Jesusworte (Unknown Sayings of Jesus / 1948 Jeremias), book. It couldn't be, however, as if nothing had happened. French scholar Jules Isaac not only denounced the influence of Christian anti-Judaism on scholarly research but also exposed the direct responsibilities of the Christian teaching of contempt for the spread of Nazi anti-Semitism and the tragedy of the Holocaust; see Jésus et Israël (Jesus and Israel / 1948 Isaac), book. Time was ripe for a new beginning. The first step was to reissue the works of French scholars Maurice Goguel and Charles Guignebert, which had been overlooked in the 1930s. The lecture Ernst Käsemann delivered on October 20, 1953 to an annual gathering of alumni from the University of Marburg, is commonly regarded as the beginning of the Second Quest for the Historical Jesus. Departing from the teachings of his former professor Rudolf Bultmann, Käsemann argued that although the gospels were theological works, they nonetheless may contain some reliable historical memories. A distinction between the historical Jesus and the risen Christ does not make sense as the gospels themselves implies a continuity between these two figures. The enormous success of Günther Bornkamm's 1956 book Jesus of Nazareth gave momentum for the second quest. The discovery and publication of the Dead Sea Scrolls offered promising contributions to the understanding of ancient Jewish messianism and even to some difficulties in the chronology of the gospels. By the end of the decade scholars were persuaded that a new Quest had started (see James M. Robinson).

|

Texts

Life of Jesus

People

Categories

Cognate Fields

|

Pages in category "Historical Jesus Studies"

The following 181 pages are in this category, out of 181 total.

- Historical Jesus Studies (1450s)

- Historical Jesus Studies (1500s)

- Historical Jesus Studies (1600s)

- Historical Jesus Studies (1700s)

- Historical Jesus Studies (1800s)

- Historical Jesus Studies (1850s)

- Historical Jesus Studies (1900s)

- Historical Jesus Studies (1910s)

- Historical Jesus Studies (1920s)

- Historical Jesus Studies (1930s)

- Historical Jesus Studies (1940s)

- Historical Jesus Studies (1950s)

- Historical Jesus Studies (1960s)

- Historical Jesus Studies (1970s)

- Historical Jesus Studies (1980s)

- Historical Jesus Studies (1990s)

- Historical Jesus Studies (2000s)

- Historical Jesus Studies (2010s)

- Historical Jesus Studies (2020s)

*

~

- Ludolph of Saxony (M / Germany, c.1295-1378), scholar

- Antonio Cornazzano (M / Italy, 1430c-1484), poet

- Martin Luther (M / Germany, 1483-1546), scholar

- Pietro Aretino (M / Italy, 1492-1556), novelist

- Bartolomeo Dionigi (M / Italy, 1544-1613), scholar

- Bernardin de Montereul (1596-1646), scholar

- Nicola Avancini (M / Italy, 1611-1686), scholar

- Pjetër Bogdani (1630–1689), Albanian scholar

- Sophia Elisabet Brenner (F / Sweden, 1659-1730), poet

- Thomas Woolston (1668-1733), scholar

- Peter Annet (1693-1769), scholar

- John Cameron (M / Britain, 1724-1799), novelist

- Friedrich Gottlieb Klopstock (M / Germany, 1724-1803), poet

- Francesco Pertusati (M / Italy, 1741-1823), translator

- Charles François Dupuis (1742-1809), scholar

- Constantin-François Volney (1757-1820), scholar

- Antonio Cesari (M / Italy, 1760-1828), scholar

- Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel (1770-1831), scholar

- Ferdinand Christian Baur (1792-1860), scholar

- Aurelio Bianchi-Giovini (M / Italy, 1799-1862), scholar

- Émile Littré (M / France, 1801-1881), translator

- Giuseppe Lorini (M / Italy, 1801-1854), scholar

- Joseph Holt Ingraham (1809-1860), novelist

- Kersey Graves (1813-1883), nonfiction writer

- Filippo De Boni (M / Italy, 1816-1870), translator

- Vito Fornari (M / Italy, 1821-1900), scholar

- Luigi Arosio (M / Italy, 1822-1901), scholar

- Ernest Renan (M / France, 1823-1892), scholar

- Lew Wallace (M / United States, 1827-1905), novelist

- Gerald Massey (1828-1907), nonfiction writer

- Giovanni Bovio (M / Italy, 1837-1903), playwright

- Constant Fouard (1837-1903), scholar

- Louis Jacolliot (1837-1890), nonfiction writer

- Émile Le Camus (1839-1906), scholar

- Georg Brandes (M / Denmark, 1842-1927), nonfiction writer

- Edwin Johnson (1842-1901), scholar

- James Stalker (M / Britain, 1848-1927), scholar

- Theodor J. Plange, nonfiction writer

- Marcello Caraccio (M / Italy, 1851-1928), scholar

- George Moore (1852-1933), novelist & playwright

- Thomas Alexander Lacey (1853-1931), author

- George Holley Gilbert (1854-1930), scholar

- Giuseppe Ballerini (1857-1933), scholar

- Ferdinand Prat (1857-1938), scholar

- Claude G. Montefiore (1858-1938), scholar

- Mangasar M. Mangasarian (1859-1943), nonfiction writer

- William Wrede (1859-1906), scholar

- Giovanni Rosadi (1862-1925), nonfiction writer

- Andrzej Niemojewski (1864-1921), scholar

- Arthur Drews (1865-1935), scholar

- Luigi Gramatica (M / Italy, 1865-1935), translator

- Emilio Bossi (1870-1920), nonfiction writer

- Edgar J. Goodspeed (1871-1962), scholar

- Giacomo Mezzacasa (1871-1955), scholar

- Shirley Jackson Case (1872-1947), scholar

- Edmond A. Fleg (M / France, 1874-1963), novelist

- Joseph Klausner (M / Lithuania, Palestine, 1874-1958), scholar

- Albert Schweitzer (1875-1965), scholar

- Aladár Zubriczky (1872-1926), scholar

- Harry Emerson Fosdick (1878-1969), scholar

- Paul P. Levertoff (1878-1954), scholar & translator

- Sholem Asch (1880-1957), novelist

- Enrique García-Velloso (M / Argentina, 1880-1938), playwright

- Olive May Winchester (F / United States, 1880-1947), scholar

- Ernesto Buonaiuti (M / Italy, 1881-1946), scholar

- Herbert Cutner (1881-1969), nonfiction writer

- Giovanni Papini (M / Italy, 1881-1956), novelist

- Renato Souvarine (1881-1958), nonfiction writer

- Henry Joel Cadbury (1883-1974), scholar

- Kahlil Gibran (1883-1931), poet

- Abraham Mitrie Rihbany (1869-1944), scholar

- Rudolf Karl Bultmann (1884-1976), scholar

- Charles Harold Dodd (1884-1973), scholar

- François Mauriac (M / France, 1885-1970), novelist

- Bruce Barton (1886-1967), nonfiction writer

- Luigi Salvatorelli (1886-1974), scholar

- Mary Redington Ely Lyman (1887-1975), scholar

- Millar Burrows (1889-1980), American scholar

- Giuseppe Ricciotti (M / Italy, 1890-1964), scholar

- Karl Ludwig Schmidt (1891-1956), scholar

- Solomon Zeitlin (M / United States, 1892-1976), scholar

- Dorothy L. Sayers (F / Britain, 1893-1957), playwright

- Nathan Bistritzky (M / Israel, 1896-1980), playwright

- Robert Aron (1898-1975), writer

- Oscar Cullmann (1902-1999), scholar

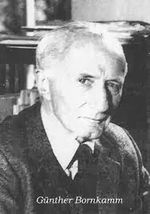

- Günther Bornkamm (1905-1990), scholar

- Pierre Benoit (1906-1987), scholar

- Iosif A. Kryvelev (M / Russia, 1906-1991), scholar

- Haim Cohn (1911-2002), nonfiction writer

- Samuel Sandmel (1911-1979), scholar

- Jean Grosjean (M / France, 1912-2006), novelist

- Annie Jaubert (F / France, 1912-1980), scholar

- Marcello Craveri (1914-2002), nonfiction writer

- Michael Grant (1914-2004), scholar

- Edward Schillebeeckx (1914-2009), scholar

- Joel Carmichael (1915-2006), nonfiction writer

- Otto Betz (1917-2005), scholar

- David Flusser (1917-2000), scholar

- Alvar Ellegård (1919-2008), scholar

- Hugh Anderson (1920-2003), scholar

- John Marco Allegro (1923-1988), British scholar

- Desmond Stewart (1924-1981), British author

- Géza Vermès (M / Hungary, Britain, 1924-2013), scholar

- Gore Vidal (1925-2012), novelist

- Robert W. Funk (1926-2005), scholar

- Elisabeth Moltmann-Wendel (M / Germany, 1926-2016), scholar

- George Albert Wells (1926-2017), nonfiction writer

- Hendrikus Boers (1928-2007), scholar

- Raymond E. Brown (1928-1998), scholar

- Joachim Gnilka (1928-2018), scholar

- Leander E. Keck (b.1928), scholar

- Tom Harpur (1929-2017), scholar

- Charles Perrot (1929-2013), scholar

- Anthony Ernest Harvey (1930-2018), scholar

- Paolo Sacchi (M / Italy, 1930), scholar

- Dolores Cannon (F / United States, 1931-2014), visionary

- Gérald Messadié (1931-2018), novelist

- Josep Montserrat Torrents (1932-), scholar

- Petr Pokorný (M / Czechia, 1933-2020), scholar

- Giuseppe Barbaglio (1934-2007), scholar

- Raniero Cantalamessa

- Luigi Cascioli (1934-2010), nonfiction writer

- John Dominic Crossan (b.1934), scholar

- Corrado Augias (b.1935), nonfiction writer

- Ed Parish Sanders (M / United States, 1937), scholar

- Giorgio Jossa (1938-), scholar

- Per Bilde, scholar

- James D.G. Dunn (M / Britain, 1939-2020), scholar

- John K. Riches, scholar

- Klaus Berger (M / Germany, 1940-2020) scholar

- James H. Charlesworth (1940-), scholar

- Earl Doherty (b.1941), nonfiction writer

- Vittorio Messori (b.1941), nonfiction writer

- Mauro Pesce (1941-), scholar

- Maurice Casey (1942-2014), British scholar

- Giancarlo Gaeta (b.1942), scholar

- John P. Meier (b.1942), scholar

- Thomas L. Brodie (b.1943), scholar

- Gerd Theissen (M / Germany, 1943), scholar, novelist

- Etienne Nodet (1944-), scholar

- Daniel Boyarin (M / United States, 1946), scholar

- Francesco Carotta (b.1946), nonfiction writer

- Bill O'Reilly (b.1949), nonfiction writer

- Jack Miles (b.1942), writer

- Piergiorgio Odifreddi (b.1950), nonfiction writer

- Jean Rouaud

- Robert M. Price (b.1954), scholar

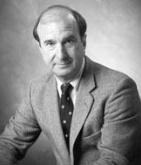

- Bart D. Ehrman (1955-), scholar

- Amy-Jill Levine (F / United States, 1956), scholar

- Gabriele Boccaccini (b.1958), Italian-American scholar

- Antonio Socci (b.1959), nonfiction writer

- Henryk Drawnel (b.1963), Polish scholar

- Anthony Le Donne

- Pierpaolo Bertalotto (1978-), scholar

- William M. Linden (1932-2012), scholar

- Oscar Larson

Media in category "Historical Jesus Studies"

The following 34 files are in this category, out of 34 total.

- 1718 Toland.jpg 500 × 500; 135 KB

- 1778 * Reimarus - Lessing.jpg 1,000 × 1,666; 556 KB

- 1795 * Hegel.jpg 320 × 500; 21 KB

- 1828 Paulus.jpg 907 × 1,360; 72 KB

- 1835 * Strauss.jpg 765 × 1,261; 248 KB

- 1863 * Renan.jpg 313 × 500; 37 KB

- 1880 * Wallace (novel).jpg 333 × 499; 34 KB

- 1883 * Edersheim.jpg 318 × 473; 20 KB

- 1901 * Wrede.jpg 319 × 499; 16 KB

- 1906 * Schweitzer.jpg 265 × 380; 31 KB

- 1921 * Papini (novel).jpg 333 × 499; 25 KB

- 1925 * Klausner en.jpg 309 × 500; 19 KB

- 1933 * Guignebert.jpg 318 × 473; 42 KB

- 1939 * Asch (novel).jpg 290 × 500; 36 KB

- 1949 * Fosdick.jpg 330 × 499; 26 KB

- 1956 * Bornkamm.jpg 305 × 500; 18 KB

- 1967 * Anderson.jpg 346 × 500; 29 KB

- 1967 * Perrin.jpg 480 × 640; 22 KB

- 1977 * Grant.jpg 375 × 499; 36 KB

- 1985 * Sanders.jpg 316 × 499; 20 KB

- 1986 * Beasley-Murray.jpg 333 × 499; 29 KB

- 1988 * Charlesworth.jpg 322 × 499; 29 KB

- 1991 * Crossan.jpg 326 × 499; 28 KB

- 1992 * Vidal (novel).jpg 343 × 499; 37 KB

- 1992 * Wilson.jpg 318 × 390; 36 KB

- 1993 * Sanders.jpg 322 × 499; 27 KB

- 1994 * Crossan.jpg 328 × 500; 45 KB

- 1999 * Ehrman.jpg 328 × 499; 60 KB

- 1999 * Fredriksen.jpg 323 × 499; 41 KB

- 2003 * Brown (novel).jpg 279 × 498; 39 KB

- 2010 * Casey.jpg 326 × 499; 39 KB

- 2012 * Boyarin.jpg 344 × 499; 53 KB

- 2013 * Aslan.jpg 324 × 499; 36 KB

- 2021-T * Wassen en.jpg 333 × 499; 43 KB