Category:Enochic Studies--1500s

|

The page: Enochic Studies--1500s, includes (in chronological order) scholarly and literary works in the field of Enochic Studies, made in the 16th century, or between 1500 and 1599.

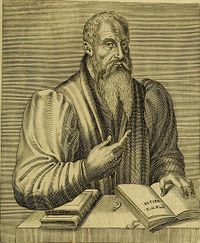

EnS 1500s -- History of research -- Overview "Christian Cabalists" continued to be the frontrunners in the search for the "lost" book(s) of Enoch. Johannes Reuchlin was well acquainted with the cultural activities at the Hospitium fratrum Indianorum established in Rome in 1481. He was in correspondence with Johannes Potken who in 1513 co-edited with the Ethiopian friar Thomas Walda Samuel the first book ever printed in Ethiopic (Alphabetum seu potius syllabarium literarum Chaldaerarum, Rome, 1513). Yet no major progress was accomplished concerning the book of Enoch. In De arte cabalistica (1517) Reuchlin reported, with some skepticism, that Pico had it as one of the "seventy secret books of Ezra," ignoring that Pico had instead only a Hebrew ms (and Latin translation) of Menahem Recanati's work, of which the editio princeps was published in 1523 and a commentary by Mordecai Jaffe appeared in 1595. In 1516 Enoch is mentioned, together with Elijah, in the epic poem, Orlando furioso by Ludovico Ariosto, as the ones that the apostle John met there when he also was taken into Heaven, where they are destined to stay until the second coming of Christ. The interest in Enochic traditions was strengthened in 1520 by the publication of Grosseteste’s Latin version of the Testaments of the Twelve Patriarchs, of which the first translations in English (anonymous) and German (Menrad Molther) also appeared. The canonical controversies of the Reformation led commentaries (both Catholic and Protestant) on the Letter of Jude to openly discuss whether the "canonical" author was legitimated in quoting as the saying of a "prophet" a text that Jerome would label as "apocryphal". The debate focused on the canonicity of Jude and yet reveals the different understanding of the sayings of Enoch among Christian theologians and intellectuals of the time. Desiderius Erasmus (1520) questioned the authorship, authenticity, and contents of the book of Enoch which in his view was a later "apocryphal" forgery. Most interpreters, including Martin Luther, Pellikan, Calvin, and Ridley, looked at the prophecy ascribed to Enoch as an inferior "apocryphal" form of revelation. Luther (1524) and Calvin, in particular, were skeptical about the existence of a book of Enoch and thought that Jude's quotation was rather based on some ancient oral traditions. And yet they all agreed in defending the authenticity of the prophecy that went back to Enoch himself. Authors like Lefèvre D’Étaples (1527) and Catharinus (1551) voiced an even more positive view. They fully accepted Tertullian's statement that the book of Enoch was preserved by Noah in the ark, passed down to his descendants, and hidden or rejected by the Hebrews after the times of the apostles; no negative emphasis should be then given to the label "apocryphal" applied by Jerome to the Book of Enoch as it simply indicated that the book, once available to the Hebrews, was now "hidden" from or "unknown" to us. The figure of Enoch remained popular in esoteric circles all around Europe. In 1530 the Venetian alchemist Giovanni Agostino Panteo published 26 charachters purporting to be the pre-Flood "Enochian" alphabet. The "rediscovery" of this alphabet was not the result of philological studies but of magical knowledge; after all, as Hermetic author Zosimos of Panopolis wrote in the 3rd-4th century, the art of alchemy was believed to be at the core of the ancient pre-deluge science. It was one of the secret knowledges taught by the fallen angels and inscribed after the Flood in the Book of Chemes, who was identified with Cam, the son of Noah and descendent of Enoch. Expectations of the "return" of Enoch continued to be very strong in millenaristic circles. In 1524, Martin Luther himself had to intervene to disprove these beliefs in his commentary on the Letter to Jude. The most notable incident occurred in 1533-34; after Melchior Hofmann predicted that Christ would return to earth, the anabaptist Jan Matthys ruled the city of Munster, Germany as the "New Jerusalem," declaring that he was the prophet Enoch redivivus. Matthys died during the siege of the city, when on Easter Sunday made a sally forth with thirty followers, convinced that Judgment Day had come. In the meantime, the relations between Europa and Ethiopia had become closer and Ethiopia gradually abandoned its traditional isolationism. When Portuguese diplomat and explorer Pêro da Covilhã arrived in Ethiopia in 1490, he was allowed to stay but not to leave the country. In 1520, however, a Portuguese embassy was welcomed for a visit and diplomatic relations were established between Ethiopia and Portugal. The embassy's chaplain Francisco Alvares composed the first description of the country, then published in Portuguese (Lisbon, 1540) and Italian. The Hospitium fratrum Indianorum in Rome also benefitted from the arrival of Ethiopian pilgrims and scholars. From 1537 to 1552, Tasfa Seyon, known as Peter the Indian, edited in Rome the first printed edition of the New Testament in Ge’ez, the Ethiopian liturgical language. Tasfa Seyon belonged to a new generation of Ethiopian scholars who were well acquainted with the new canonical status acquired by the book of Enoch as a result of the reforms of Emperor Zar'a Ya'qob in the 15th century. Most of the earliest mss of 1 Enoch, or on 1 Enoch, date from that period. Not accidentally, this was the time in which news of the existence of the Book of Enoch and of its canonical status in Ethiopia eventually spread in Europe. The first report came in mid-16th century by French Christian Cabalist Guillaume Postel. In 1551 in De Etruriae regionis Guillaume declared that the Enoch's prophesies made before the Flood were preserved in the archives of the Queen of Sheba and that to this day they were believed to be canonical scripture in Ethiopia. In 1553 he wrote in his De originibus that in Rome (most likely, in 1547) he had met an Abyssinian priest (apparently, Tasfa Seyon himself) who illustrated him the content of 1 Enoch. Postel's piece of information was included in 1559 by British playwright John Bale in his popular work on Scriptorum Illustrium maioris Brytanniae posterior pars (Basel 1559). According to Luis de Urreta, the Librarian of the Vatican Apostolic Library Guglielmo Sirleto also was made aware of the existence of the Book of Enoch in Ethiopia by two friers who visited the country (in 1579?) as members of a delegation sent by Pope Gregory XIII to the Ethiopian King. To the popularity of book of Enoch largely contributed also the publication of the Testaments of the Twelve Patriarchs in a new English translation by Anthony Gilby (The Testaments of the Twelve Patriarchs, the Sonnes of Jacob, 1574); the work, often reprinted, remained a standard version of the text for almost three centuries. By the second half of the 16th century, the notion of the existence of an ancient book (or books) of Enoch was widespread and the connection between Enoch and Ethiopia was also firmly established. In 1577 Serafino Razzi in his Vite dei santi, e beati cosi uomini, come donne del sacro ordine de’ Frati Predicatori introduced the biographies of several Ethiopian saints, including Saint Thaclauareth, who "like Enoch redivivus, was revealed the entire order of the heavens." And yet, in spite of all these complex connections between Enoch and Ethiopia, no progress was made in the recovery of the actual text of the book of Enoch. The idea that magic and alchemy could provide a shortcut continued to fascinate European intellectual circles. In his Introductio in divinam Chemiae artem (Basel 1572) Petrus Bonus repeated Roger Bacon's remarks that Henoch was the great Hermogenes. News from Postel and Bale about the existence of the Book of Enoch (and the frustration about the lack of progress in its recovery) inspired British alchemist John Dee to follow the same path as Panteo. In May 1581 some promising yet inconclusive experiments with the crystal ball convinced Dee that he needed the services of a professional scryer to communicate with the spirits. In 1582-83 Dee formed a partnership with visionary Edward Kelley in the search for the lost wisdom of Enoch. The result was the "discovery" of a mysterious alphabet they claimed to have received from the archangel Michael, and portions of the Book of Enoch written in the "Enochian language" they believed Enoch himself used to communicate with the angels. @2014 Gabriele Boccaccini, University of Michigan Picture gallery |

EnS 1500s -- Highlights

English -- French -- German -- Italian -- Spanish -/- Danish -- Dutch -- Greek -- Hebrew -- Hungarian -- Japanese -- Latin -- Portuguese -- Russian

|

Pages in category "Enochic Studies--1500s"

The following 20 pages are in this category, out of 20 total.

1

- Orlando furioso (The Frenzy of Orlando / 1516 Ariosto), Italian poem

- De arte cabalistica (1517 Reuchlin), book

- Testamenta duodecim patriarcharum filiorum Jacob (1520 Grosseteste), book

- פירוש על התורה (Commentary to the Torah / 1523 Recanati), book (Hebrew / ed. princeps)

- Die ander Epistel S. Petri und eyne S. Judas (1524 Luther), book

- De harmonia mundi totīus cantica tria (1525 Zorzi), book

- Commentarii in Epistolas catholicas (1527 Lefèvre), book

- Voarchadumia contra alchimiam (1530 Panteo), book

- Pentagruel et Gargantua (1532-34 Rabelais), novel

- An Exposition vpon the Epistle of Jude ye Apostle of Christ (1549 Ridley), book

- Commentaria in omnes divi Pauli, et alias septem canonicas epistola (1551 Pellicanus), book

- De Etruriae regionis (1551 Postel), book

- De originibus seu de varia ... Latino incognita historia totius Orientis (1553 Postel), book

- Scriptorum illustrium maioris Brytanniae posterior pars (1559 Bale), book

- The Testaments of the Twelve Patriarchs, the Sonnes of Jacob (1574 Gilby), book

- Vite dei santi e beati del sacro ordine dei frati predicatori (1577 Razzi), book

- Liber mysteriorum (1583 Dee, Kelley), ms

- לבוש מלכות (Robes of Royalty / 1595 Jaffe), book (Hebrew)