Category:Mischlinge (subject)

Mischlinge ["mixed race"] (see Holocaust Children Studies)

Overview

"Mischlinge" was the legal term used in Nazi Germany to denote persons deemed to have both Aryan and Jewish ancestry.

Legal definition

Nazism believed that the Nordic Race/Culture constituted a superior branch of humanity, and viewed International Jewry as a parasitic and inferior race, determined to corrupt and exterminate both Nordic peoples and their culture through Rassenschande ("racial pollution") and cultural corruption.

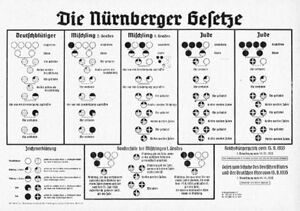

As defined by the Nuremberg Laws in 1935, a Jew was a person – regardless of religious affiliation or self-identification – who had at least three grandparents who had been enrolled with a Jewish congregation. A person with two Jewish grandparents was also legally "Jewish" if that person met any of these conditions:

- Was enrolled as member of a Jewish congregation when the Nuremberg Laws were issued, or joined later.

- Was married to a Jew.

- Was the offspring from a marriage with a Jew, which was concluded after the ban on mixed marriages.

- Was the offspring of an extramarital affair with a Jew, born out of wedlock after 31 July 1936.

A person who did not belong to any of these categorical conditions but had two Jewish grandparents was classified as a Jewish Mischling of the first degree. A person with only one Jewish grandparent was classified as a Mischling of the second degree.

The majority of 1st- or 2nd-degree Mischlinge were (at least formally) "Christian" (57% Protestant, 41% Catholics), only 1% of them identified themselves as Jews. A considerable number of "Christian" Mischlinge, however, were such only by name and were de facto "non-religious".

Requests for reclassification (e.g., Jew to Mischling of 1st degree, Mischling of 1st degree to 2nd degree, etc. ) or Aryanization were personally reviewed by Adolf Hitler and were considered an act of grace. Reclassification could also be obtained by way of declaratory judgment in court, usually following (false) admission of adultery by (grand)mothers. The process gave way to bribery, extortion, abuses, and other subterfuges concerning documentation of who was, or was not, a Jew.

Living as a Mischling

“Mischlinge” were “temporary citizens” of Germany, tolerated by the grace of the Nazi government. Yet they lived in a constant state of uncertainty. They never knew when the laws protecting them would change or when friends, neighbors, and colleagues would turn against them.

1st-degree Mischling children, more so than those of 2nd-degree, had restricted access to higher education and were generally forbidden from attending such schools in 1942.

Those who were considered Mischlinge were generally restricted in their options of partners and marriage. Mischlinge of first degree generally needed permission to marry, and usually only to other Mischlinge or Jewish-classified persons. Mischlinge of second degree did not need permission to marry a spouse classified as Aryan; however, marriage with Mischlinge of any degree was unwelcome.

Nazi policies were designed not only to forbid mixed marriages but also to encourage the remaining intermarried couples to divorce – they both could lose their jobs, which put a strain on the marriage, and non-Jews would ostracize them.

Among stigmatized intermarried couples there was a hierarchy. Families with an Aryan husband and baptized children were part of the category classified as “privileged mixed marriages”: they received better rations and the Jewish wife did not have to wear the yellow Star of David. Families with a Jewish husband and children raised Jewish, on the other hand, did not experience such favorable treatment. It was, again, a way for the government to pressure intermarried couples to divorce and convince the non-Jew to re-join the Volksgemeinschaft, or “Aryan community of blood.”

The Final Solution

At first, intermarried couples and their children were protected from deportations and ghettoization, and Mischlinge could even join the Hitler Youth and the German army. The reason for this leniency was to avoid arousing suspicion or protest from non-Jewish family members and to encourage Mischlinge to integrate into Aryan society.

At the Wannsee Conference of January, 20, 1942, it was suggested that if Mischlinge were not deported to a concentration camp, they should at least be sterilized. Hitler and Goehring, however, were reluctant to anger and alienate the German people. They feared a public outcry from the Aryan relatives of Mischlinge, especially after Stalingrad. So nothing happened at the time, at least not on a national scale.

As the war went on, however, Nazi tolerance of Mischlinge and their parents waned. With the Final Solution fully underway, Nazi officials did not want any Jews to be spared.

In some regions, Nazis attempted to get around laws prohibiting deportation and imprisonment of intermarried Jews by saying the roundups were for “protective custody.” In several regions, this “protective custody” resulted in the deaths of intermarried Jews in Auschwitz, at a time when they were officially exempt from deportation. In general, while the classifications of Mischling applied in occupied Western and Central Europe, and were well-documented for the Netherlands and Protectorate Bohemia and Moravia, this was not the case in Eastern Europe. Persons who would have been deemed Jewish Mischlinge, in the East were classified as Jews in German-annexed Poland, German-occupied Poland, German-occupied parts of the Soviet Union, and the German-occupied Soviet-annexed Baltic/Eastern Polish territories.

There’s no doubt that had the war lasted longer, had Hitler won, the Mischlinge would have also been exterminated. Hitler called them “monstrosities, halfway between man and ape.”

Beginning in 1944, a large number of intermarried Jews were put into segregated labor battalions of the Todt Organization (OT).

By January 1945, the Reich Security Main Office lifted its protection for intermarried Jews and ordered all remaining Jews deported. However, the success of these deportations and the number of Jews deported varied widely by region. In some cities, only a handful of intermarried Jews and Mischlinge were deported while other cities deported the majority of the remaining Jews. In the winter of 1945, for instance, a number of German Mischlinge were deported from Hamburg to Theresienstadt. Some local authorities granted exemptions from deportation while others did not. Some regions’ infrastructures were too damaged by war to organize transports while other regions could still operate efficiently. People’s fates depended largely on the local circumstances of each city and region and the methods employed by the Nazis in charge to identify and round up the remaining Jews. Of the approximately 15,000 Jews liberated in Germany proper after the war, about 10,000 had a non-Jewish spouse. Their survival ultimately depended on a variety of factors: where they lived, whom they knew (connections), the presence or absence of a Jewish parent or grandparent.

Even in the years after the war, Mischlinge continued to struggle to rebuild their lives. Though they had also lost their homes, jobs, educations and livelihoods, intermarried Jews from the Nazi category of “privileged mixed marriages” often received lower food rations and other aid because they were perceived to not have suffered as much as other Jews had, such as being forced to wear the yellow star or live in a ghetto or concentration camp.

Pages in category "Mischlinge (subject)"

The following 25 pages are in this category, out of 25 total.

1

- Heinz Stephan Lewy (M / Germany, 1925), Holocaust survivor

- Walter Weitzmann (M / Austria, 1926), Holocaust survivor

- Fritz Gluckstein (M / Germany, 1927), Holocaust survivor

- Alexander Grothendieck (M / Germany, 1928-2014), Holocaust survivor

- Davide Schiffer (M / Italy, 1928-2020), Holocaust survivor

- Asta Berlowitz (F / Germany, 1929), Holocaust survivor

- Ilse Koehn

- Jan Chraplewski / Jan Caron (M / Germany, 1930), Holocaust survivor

- Michael Rossmann (M / Germany, 1930-2019), Holocaust survivor

- Eva Weitzmann / Eva Moore (F / Austria, 1929), Holocaust survivor

- Jakob Berlowitz / Jack Berlowitz (M / Germany, 1931-2007), Holocaust survivor

- Luigi Ferri (M / Italy, 1932), Holocaust survivor

- Luisa Soavi (F / Italy, 1932), Holocaust survivor

- Maria Levi Dalla Mutta (F / Italy, 1933-1990), Holocaust survivor

- Steve Shirley / Vera Buchthal (F / Germany, 1933), Holocaust survivor

- Samuel Berlowitz (M / Germany, 1934-1990), Holocaust survivor

- Ruth Barnett / Ruth Michaelis (F / Germany, 1935), Holocaust survivor

- Jan & Kaja Saudek

- Cesare Frustaci

- Peter Chraplewski (M / Germany, 1937), Holocaust survivor

- Sergio De Simone (M / Italy, 1937-1945), Holocaust victim

- Marione Ingram (F / Germany, 1938), Holocaust survivor

- Franco Levi (M / Italy, 1938), Holocaust survivor

- Eva Novotna (F / Czechia, 1938), Holocaust survivor

- Esther Littman Gorny (F / Germany, 1940), Holocaust survivor

Media in category "Mischlinge (subject)"

The following 5 files are in this category, out of 5 total.

- 1977 Koehn.jpg 294 × 474; 24 KB

- 2010 Barnett.jpg 328 × 499; 31 KB

- 2018 Frustaci.jpg 324 × 499; 32 KB

- 2003 Schiffer.jpg 201 × 300; 11 KB

- 2013 Ingram.jpg 313 × 500; 32 KB