Cesare Frustaci

Cesare Frustaci (M / Italy, Hungary, 1936), Holocaust survivor.

- KEYWORDS : <Italy> <Hungary> <Street Children> <Hidden Children> -- <United States>

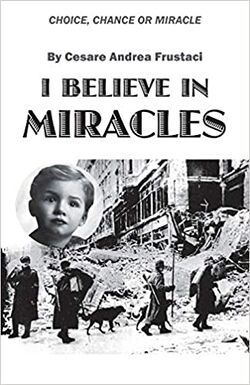

- MEMOIRS : I Believe in Miracles (2018)

Biography

Cesare Frustaci was born July 4, 1936 in Naples, Italy, to an Italian-Catholic father and a Jewish-Hungarian mother.

Book : I Believe in Miracles (2018)

"In any person’s life there is so much that is remembered, even more that is forgotten. Where a single event or decision, of one’s own making or a consequence of the times one is born into, plot the course of a life. Yet through it all, there is meaning. Life is worth living, declaring so is perhaps the most important thing one can do ... In this autobiography by Cesare Frustaci from small boy abandoned in war- torn Europe to proud grandfather thankful for the life he now lives on the gulf-coast of Florida, “Cesi” recalls his Italian-Catholic father and Jewish-Hungarian mother. His flight in the face of Nazism at age two with mother from his place of birth in Naples, Italy, to her place of birth in Budapest, Hungary ... His mother’s looming internment in the German death camps. His survival of the bloodiest war of the last century followed by a rural farm family adopting him. Not to see his father for eighteen years and to be reunited years later thanks solely to the personal intervention by Monsignor Angelo Roncalli, better known as the “Good Pope,” John XXIII ... This son of a musician who composed the music for a song played by the Glenn Miller’s U.S. Army Air Force Band, and a ballerina who trained, performed and taught at the Hungarian Opera House reveals the child who grew to manhood on the streets of an alien city under a German, then Russian occupation. Held captive by them until 20 he returns to his father in Naples only to discover greater challenges there (including his father’s Greta Garbo connection); an engineer married to a Hungarian beauty and ultimate immigration to America with wife and two daughters ... Fate did not swallow up Cesare Frustaci. Destiny, rather than crush him, submits to his rule.

The Gazette (4 April 2014)

When Cesare Frustaci was 7-years-old, his mother put him out on the streets of Budapest to fend for himself with only a pillow, a little bit of bread and a Catholic baptism certificate in his pocket. It was her way of protecting him, of hoping he would survive.

“Mother saw Jewish children being rounded up and taken to the Danube River and thrown into the river to drown,” he says. “She told me, ‘Remember, you are not a Jew but a Roman Catholic and not a Hungarian but an Italian.”

Now an American citizen living in Port Charlotte, Fla., Frustaci will tell his story in Cedar Rapids next week in honor of Holocaust Remembrance Month. He says with fewer and fewer people left to share their stories, he feels it is important to keep the memory of the Holocaust alive.

“Once we are gone, we are gone, and there will be no one to be an eyewitness,” he says. “That is why I am telling my story.”

It was a long, hard path from the streets of the Jewish ghetto in Budapest to Florida.

His mother Margit Wolf was a ballerina, married to popular Italian composer and conductor Pasquale Frustaci. Cesare Frustaci was born in Italy in 1936 and baptized as a Roman Catholic. But when he was 2-years-old, the Italian government under Benito Mussolini expelled all foreign Jews. Cesare and Wolf moved back to Hungary, leaving his father behind.

Soon after putting her son on the street, Wolf was sent with other Hungarian Jews to a series of concentration camps in Germany. Frustaci would live on the streets for several months, hiding in a dark cellar and struggling to find food.

In 1944, he was captured and sent to a youth detention center run by Jesuit priests. There was so little to eat, two of the six priests starved to death because they were giving their rations to the children.

After the Soviet army liberated the detention center in 1945, the International Red Cross placed Frustaci and the other children with families around Hungary. He was sent to live with a family in a rural village about 250 miles from Budapest.

His mother survived the concentration camps. She spent spent a year and a half looking for him, walking from village to village visiting more than 180 with a picture of him in her pocket, showing it to everyone she met. Finally, she showed the photo to a little girl who said, “That is my brother.” Wolf had found Frustaci’s adopted family, and she was reunited with her son.

After World War II ended, Hungary was behind the Soviet Iron Curtain. When he was 18, Frustaci wanted to go to Italy for college and to see his father. But after applying for an exit visa, he was accused of being a traitor to the communist government. He was imprisoned and tortured. It took the intervention of a priest, Angelo Roncalli, who would later become Pope John XXIII, to secure his release into Italy.

After his education, Frustaci worked as an executive at an engineering firm. In 1981, he was invited to work for a company in America, and he emmigrated from Europe with his wife and two daughters.

Thirty-three years later, they’re still here. Frustaci speaks with pride and emotion of the day he was personally given his permanent residency card by an American government official who welcomed him to the United States and shook his hand.

“I was very afraid and concerned because I never had a good, nice word in my life from a government official,” he says. “Instead it was one of the best experiences of my life.”

For decades, Frustaci says he did not speak about his experiences during the Holocaust.

“It’s a common characteristic of the survivors that they don’t speak. In fact, I never heard anything from my mother about what she endured in the concentration camp,” he says.

But in 2004 he heard about a Catholic priest in England who denied the Holocaust had happened.

“This made my blood boil, because I was an eyewitness,” he says. “At that point I said, ‘It is my mission for the rest of my life to educate the younger generations.’”

To further that mission, Frustaci will speak at several schools and colleges around Cedar Rapids throughout the next week, starting Monday at a Yom Hashoah Holocaust Remembrance Day service organized by The Thaler Holocaust Memorial Fund.

“It is important to come together as a community to remember and to honor those whose lives and livelihood were forever changed by the Holocaust,” said Fund board member Lena Gilbert. “We must continue to educate those in our midst in hopes that what happened during the Holocaust will never again be tolerated.”