Category:Maccabees (subject)

|

< Timeline : (1) Babylonian Exile -- (2) Persian Period -- (3) Greek Period -- (4) Maccabean Period -- (5) Roman Period -- see also Historical Jesus Studies, and Christian Origins Studies > < People : Ptolemaic Kings - Seleucid Kings - High Priests - Zadokites - Tobiads - Hasmoneans // Onias III - Heliodorus - Antiochus IV - Jason - Menelaus - Onias IV - Judas Maccabeus - Antiochus V // Spartacus // Judith - Salome Alexandra - Tigranes the Great > < Events : Heliodorus' Mission - Maccabean Revolt - Maccabean Martyrs - Hasmonean Rule - Armenian Invasion >

Maccabees -- Overview

Maccabees -- Highlights

|

|

Overview

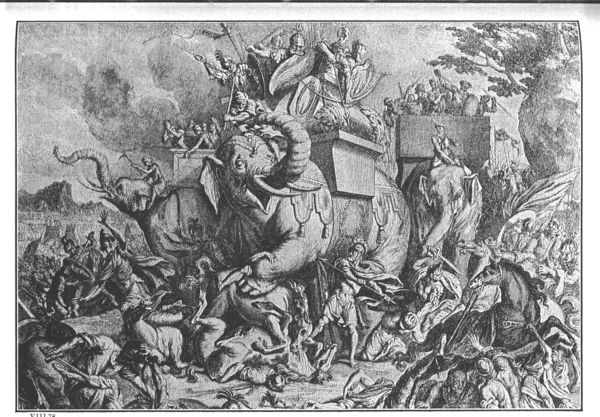

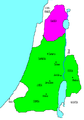

The Maccabean Revolt refers to a conflict between the Hellenistic party (led by the Seleucid king Antiochus IV and the Jewish High Priest Menelaus) and a coalition of groups led by the Maccabees, aimed to restore the Mosaic Torah as the national law of Israel.

The Maccabean Revolt is traditionally presented and celebrated in Judaism as a national war for independence and religious freedom carried our by the Jews under the leadership of the Maccabees against the Greeks.

According to Jewish post-Maccabean sources, the villain was the Seleucid king Antiochus IV, who issued a general decree "to his whole kingdom that all should be one people and that all should give up their particular customs" (1 Macc 1:41-42; cf. 2 Macc 6:). At the beginning of the second century CE, the Roman Tacitus would reverse the blame by commending Antiochus for his eagerness to eradicate the "base and abominable customs of the Jews" (Historiae V.4-7).

From the historical point of view the situation is far more complicated. Modern historians agree that Antiochus pursued a policy of tolerance of local cults and there is not evidence of widespread religious persecution outside Jerusalem and Judah. It is difficult to imagine an attempt by the king to "abolish" Judaism when his action was intended to strengthen the power of the supreme authority of Judaism and his most faithfully ally in Jerusalem, the High Priest Menelaus.

When in 169 BCE Antiochus first intervened in Jerusalem in support of Menelaus against the rebellion of Jason, "he took the silver and the gold, and the costly vessels; he took also the hidden treasures that he found" (1 Macc 1:23; cf. Ant 12:247)--"eighteen hundreds talents from the Temple" (2 Macc 5:21). "Many of the opposite party" were also slaughtered (Ant 12:247). But no episode of religious intolerance is recorded.

"Two years later" in 167 BCE, Antiochus IV sent again "Apollonius a chief collector of tribute... to Jerusalem with a large force" (1 Macc 1:29; 2 Macc 5:24; cf. Josephus, Ant 12:248). The city was taken "by treachery... pretending peace" (Josephus, Ant 12:248; 1 Macc 1:30), and then taking advantage of "the holy sabbath day" (2 Macc 2:25-26). "Great numbers of people" were killed, the Temple was emptied of its secret treasures" (Ant 2:250).

For the first time since the Hellenistic party took power in Jerusalem, the same worship in the Temple underwent radical changes: the daily sacrifices were interrupted (Dan 9:27; 1 Macc 1:45), the altar was defiled by "a desolating abomination" (Dan 9:27; 11:31; 12:11; 1 Macc 1:54), and a new calendar was introduced (Dan 7:25)--a change from the Zadokite sabbatical calendar to the Macedonian lunar calendar that would have lasting and monumental consequences in the development of Jewish thought even after the Maccabean crisis.

A large-scale religious persecution hit those who followed the Zadokite laws. "The Jews were compelled to forsake the laws of their ancestors and no longer to live by the laws of God" (2 Macc 6:1). As both the Seleucid and the Jewish priesthood agreed that the Zadokite law was no longer either the law of the king or the law of God, there was no justification in following it, nor pity for the transgressors: "Whoever does not obey the command of the king shall die" (1 Macc 1:50). The acceptance of the Greek way of life, which up to this time had been purely voluntary, was now enforced by the king's law (1 Macc 1:41-64; 2 Macc 6:1-11). Those who dared resist, were seen as political enemies and treated as such. "Many Jews complied with the king's command, either voluntarily, or out of fear of the penalty that was denounced; but the best men, and those of the noblest souls, did not regard him... on which account they every day underwent great miseries and bitter torments" (Ant 12:255-256; cf. 1 Macc 1:62-64). More than three centuries of Zadokite order came to an end amid blood shed and persecution.

It is not easy to explain such a dramatic development. Neither Antiochus IV nor the Hellenistic party had ever before forced the inhabitants of Judea to abandon the Zadokite law. The major goal of Antiochus had being that of putting his hands on the Temple treasure; the Hellenistic party sought exclusively their own freedom not to be bound by the Zadokite law, and the opportunity to join the Hellenistic society. What suddenly turned an economical quest into a religious crisis?

The circumstances of the death of Menelaus, who was ultimately executed by Antiochus V as a traitor, shed some light on what happened. The Greeks apparently thought that Menelaus "was to blame for all the trouble" (2 Macc 13:4) and specifically, for having "persuaded [Antiochus IV] to compel the Jews to leave the religion of their fathers" (Josephus, Ant 12:384), thus dragging the Seleucid monarchy to an unfortunate experience. The report sounds genuine, as it contradicts the view that the same Jewish authors previously offered of the Maccabean crisis as a religious persecution promoted by the Greeks. However, nothing is said about the motivations of Menelaus and in particular, about what happened in the two critical years, between 169 and 167 BCE, which separate the two interventions of Antiochus IV in Jerusalem. The only text that seems to apply to this period is the very confused beginning of Josephus' Jewish War (Bel 1:31-33). We read that just before Antiochus "spoiled the Temple and put a stop to the constant practice of offering a daily sacrifice," i.e., immediately before Antiochus' second intervention in 167 BCE, there was turmoil in Jerusalem. "A great sedition fell among the men of power in Judea and they had a contention about obtaining the government; while each of those who were of dignity could not endure to be subject to their equals". The authenticity of the passage is strengthened by the fact that it contradicts Josephus' own position that only after the beginning of the Maccabean revolt Alcimus was the first "who was not of the high priest stock" (Ant 12:387), to take the office. In order to save the continuity of the priesthood, Josephus would like his readers to believe that Menelaus was the "younger brother" of Onias and Jason (Ant 12:238-239; 15:41; 19:298; 20:235), not an Aaronite priest from the tribe of Bilgah. Here, on the contrary, we have evidence that the issue of being ruled by "equals" arose before and not after the Maccabean revolt. It happened when the non-Zadokite Menelaus took power, and more specifically between 169 and 167 BCE, after the death of both Onias III and Jason. Any other setting would be anachronistic.

Josephus' text contains some additional, important pieces of information, all of them consistent with the same historical setting. At that time "Antiochus had a quarrel with the sixth Ptolemy about his right to the whole country of Syria" (Bel 1:31). In 168 BCE, Ptolemy VI broke the treaty to which he had been subjected after Antiochus' first campaign in Egypt. The Roman support stopped Antiochus' military reaction abruptly and forced him to a humiliating withdrawal (cf. Polybius 29.27.8; and Livy 45.12.4ff). The defeat reopened the argument about the possession of Syria-Palestina and increased the military importance of Jerusalem. In this difficult situation, something happened in Jerusalem that must have caused not little concern in Antiochus, as it affected his major allies and leaders of the pro-Seleucid party: "the sons of Tobias [including Menelaus?] were cast out of the city and fled to Antiochus and besought him... to make an expedition into Judea" (Bel 1:31-32). The Seleucid power in the region was at stake. The king would not forget to take advantage of the war laws which allowed him to loot the Temple treasure again, but his intervention was primarily a punitive expedition against "a great multitude of those that favored Ptolemy" (Bel 30-31).

The only major problem in such a reconstruction is the reference to the Zadokite "Onias, one of the high priests" (Bel 1:31), who is said to have caused the sedition against the sons of Tobiads and then "fled to Ptolemy" when Antiochus prevailed. As in Josephus' Jewish War the same Onias is later called "the son of Simon" (Bel 7:423), this is usually taken as a puzzling and anachronistic reference to Onias III, which throws discredit on the historical reliability of the entire passage. In Jewish Antiquities, however, Josephus, after apologizing for having provided in his previous work only brief and not very accurate information on the subject (Ant 12:245), corrects himself clarifying that the Onias who fled to Egypt was not Onias III but his son, Onias IV (Ant 12:237, 387-388; 13:62-73).

When the reference to Onias at the beginning of the Jewish War also is taken as a reference to Onias IV, then the text becomes clear. At that time Onias IV was still a child (cf. Josephus, Ant 12:237), yet after the murder of his father and the death in exile of his uncle Jason, he was in pectore the legitimate high priest according to the Zadokite succession. His coming to age brought up for discussion again the future of the Jerusalem priesthood. More than securing Menelaus loyalty and consensus, the common Aaronite descent stirred up the jealousy of many of his fellow priests or "equals," who would have rather seen the Zadokite line restored. When the party that supported "Onias (IV) got the better" (Bel 1:31), Menelaus and the Sons of Tobias sought Antiochus IV's support accusing their enemies to side with the Ptolemies. After the failure of his second Egyptian campaign, Antiochus had a strategic interest in strengthening his military presence in Jerusalem and avoiding the coalescence of any opposition that could be used by the Ptolomeis as a fifth column ready to rise and betray. Menelaus needed a sign of discontinuity that would definitively affirm his power and the legitimacy of his priesthood over the Zadokites, also from the religious point of view. As the author of the Letter to the Hebrews would say in a different historical context but addressing a similar theological problem: "When there is a change in the priesthood, there is necessarily a change in the law as well" (Hebrews 7:12). The abolishment of the Zadokite law served well both the interests of Menelaus and the king.

Even in this outbreak of violence, the goal of Menelaus and Antiochus was not to abolish Judaism, but only the Zadokite kind of Judaism. As Paolo Sacchi points out, "no one wants to become the high priest to a god in liquidation." Menelaus had succeeded in becoming the high priest of a well-established sanctuary of a well-established religion. He had neither any intention nor any interest in undermining the roots of his power and wealth. Given the economic and political importance of sanctuaries in the Hellenistic world, the king's goal was to take control of the Jerusalem Temple not certainly to destroy it. The religious persecution was limited in time and in space; it aimed not to fight the Jews and the Jewish religion but only to hit the king's political enemies in Jerusalem. "From the perspective of hindsight... it is clear that the debate was not between Judaism and Hellenism as opposed forced, but really over the degree to which an already hellenized Judaism would self-consciously conform even further to international cultural norms" (Martin S. Jaffee)

Within this context, it is likely that Menelaus himself directed the king by suggesting him those measures that in a very simple and effective way could identify their enemies and lead to their punishment. "The very fact that Antiochus was able to individuate precisely which Jewish practices to abolish demonstrates that the person advising him on the matter knew the Judaism of the period very well and wanted to destroy that particular Judaism, not all Judaism" (Paolo Sacchi).

Without a hint from the high priest in Jerusalem, Antiochus would have never so ferociously ban circumcision as the mark of separation between Jews and Gentiles (2 Macc 6:10), or introduced pigs as sacrificial animals and forced Jews to consume them (1 Macc 1:47: 2 Macc 6:21; 7:1), which was not customary among the Greeks and was an abomination for most of the peoples of the region.

Without a hint from the high priest in Jerusalem, Antiochus would have never "defiled the sanctuary and the priests" (1 Macc 1:46) by actually erecting a new altar and offering magnificent sacrifices on it (1 Macc 1:54; 2 Macc 6:7; Dan 11:31; 12:11), or "building altars in the surroundings towns of Judah and offering incense at the doors of the houses and in the streets" (1 Macc 1:54-55). Only in the eyes of the Zadokite law, these measures were an abomination as they challenged the holiness and uniqueness of the Jerusalem Temple. In every other context the same measures of benevolent patronage would have sounded as a sign of the king's favor and respect to the Temple of Jerusalem, which Antiochus did not destroy but honored, and to his priesthood, which Antiochus did not persecuted but supported.

Without a hint from the high priest in Jerusalem, Antiochus would have never commanded "to profane sabbaths and festivals" (1 Macc 1:45), or "to change the sacred seasons" by introducing a new calendar in the Temple (Dan 7:25), which altered the holiness of times which in the Zadokite worldview was no less crucial than that of people and places.

All these measures implied an inside knowledge of the Zadokite law and a conscious and well-meditated plan aimed not to eradicate the religion of the Jews but on the contrary to affirm the importance of the Jerusalem cult under the new priesthood of Menelaus, while targeting the boundaries of separation within people and animals, places, and times as established by the Zadokite purity laws. Antiochus had vital political and military interests in Jerusalem; Menelaus knew that only the support of the king could give legitimacy to the new priesthood. Both wanted to get rid of their enemies. Antiochus had the power, but only Menelaus could articulate a plan of religious reforms that would serve both well. Antiochus trusted and supported him.

What Antiochus IV and Menelaus did not foretell, however, was that the punishment of their enemies would ignite the flames of a ruinous civil war. The unexpected opposition came not from the nostalgic of the Zadokite or Ptolemaic power but from those who, mostly in the countryside outside Jerusalem, more heavily had to bear the burden of taxation while being excluded from the benefits of Hellenistic economy and culture. The catalysts were "a priestly family of Joarib," the Hasmoneans or Maccabees as they were soon called out of admiration for the military skill of Judah. Soon, the conflict escalated into a large-scale civil war.

The genius of the Maccabees was to present themselves not as the leaders of just another rival priestly family seeking for power, as they were, but as the champions of the national tradition against the Greeks, and to turn the civil war into a war of liberation against the foreign oppressors. The Maccabean propaganda presents Antiochus' measures in Judah not as the result of infra-Jewish conflicts but as the last chapter and inevitable outcome of the opposition between Hellenism and Judaism (1 Macc 1:1-10).

Around the military and political leadership of the Maccabees a varied coalition of groups arose, with different religious or political agendas, but united in their opposition to Menelaus. Their victory would mark the restoration of the Mosaic law and its transformation from the law of the House of Zadok into the national law of all Jews. Their victory also meant the defeat of any hypothesis of inclusive monotheism; from now on, any form of Judaism will have to define itself as exclusive monotheism. Religious conflicts however did not cease, even when the Maccabees reached complete independence as the new high priests and kings of Judah. Competitive interpretations of the crisis emerged and clashed. Judaism would remain a profoundly divided society.

Pages in category "Maccabees (subject)"

The following 200 pages are in this category, out of 247 total.

(previous page) (next page)1

- == == 1450s == == ==

- Storie sacre (Sacred Narratives / 1475c Tornabuoni), poetry

- == == 1500s == == ==

- Maccabean Shrine (1527 Hanemann), art

- Expulsion of Heliodorus from the Temple (1512 Raphael), art

- Judita (Judith / 1521 Marulić), poetry (Croatian)

- Iudith (1532 Birck), play

- Judith mit Holophernes (1551 Sachs), play

- Die Maccabäer (1552 Sachs), play

- Rivus Cedron (1561 Conradinus), poetry

- La gloriosa e trionfante vittoria donata dal grande Iddio al popolo hebreo per mezzo di Giuditta sua fidelissima serva (1564 Sacchetti), play

- Eleazarus Machabaeus (1587 Pontanus), play

- Love's Labour's Lost (1594 Shakespeare), play

- Divine & heureuse victoire des Machabées sur le Roi Antiochus (1596 Virey du Gravier), play

- La Machabée (1596 Virey du Gravier), play

- Judas Maccabaeus (1601 Haughton), play

- In sacros divinorvm Bibliorvm libros, Tobiam, Ivdith, Esther, Machabaeos, commentarius (1610 Serarius), book

- Le turbolenze d'Israele, seguite sotto 'l governo di duo rè Seleuco il Filopatore ed Antioco il Nobile (1633 Manzini), book

- The Triumph of Judas Maccabeus (1636 Rubens), art

- Judas Macabeo (1641 Calderón de la Barca), play

- Commentaria in libros Machabaeorum (1651 Redanus), book

- Expulsion of Heliodorus from the Temple (1662 Flémal), art

- Commentarii historici et morales perpetui ad secundum Machabaeorum librum (1664 Foullon), book

- Li Maccabei (The Maccabees / 1674 Bicilli / Mazzei), oratorio

- Expulsion of Heliodorus from the Temple (1674 Lairesse), art

- Die Makkabäische Mutter mit ihren sieben Sohnen (1679 Franck / Elmenhorst), oratorio

- La madre de' Maccabei (The Mother of the Maccabean Martyrs / 1685 Mercuriali / Gigli), oratorio

- The History of the Nine Worthies of the World (1687 Burton), novel

- La madre de' Maccabei (The Mother of the Maccabean Martyrs / 1688 Fabbrini / 1685 Gigli), oratorio

- Liber Tobiae, Judith, Oratio Manassae, Sapientia, et Ecclesiasticus Graecè et Latine (OT Apocrypha / 1691 Fabricius), book

- Judas Machabeus (1695 Cola), oratorio

- Juda Machabeus (1697 Pulci), oratorio

- Judae Machabei gloriosa in Deum fiducia (1702 Adolph), play

- La madre de' Maccabei (The Mother of the Maccabean Martyrs / 1704 Ariosti / 1685 Gigli), oratorio

- Mater Machabaeorum (1704 Arresti), oratorio

- La madre de' Maccabei (The Mother of the Maccabean Martyrs / 1705 Aldrovandini / 1685 Gigli), oratorio

- Il martirio de' Maccabei (1709 Badia / Stampiglia), oratorio

- La donna forte nella madre dei sette Maccabei (1714 Fux / Pariati), oratorio

- La madre de’ Maccabei (1719 Massarotti), oratorio

- Les Machabées (1721 La Motte), play

- Antiochus; ou, Les Machabées (1722 Nadal), play

- Jonathas le Machabée (1723 Père de la Sante), play

- Expulsion of Heliodorus from the Temple (1725 Solimena), art

- Spartaco (Spartacus / 1726 Porsile / Pasquini), opera (music & libretto)

- Heliodorus and Onias (1726 Tiepolo), art

- Matatia in Modin (1727 Redi), oratorio

- L'osservanza della divina legge martirio de' Maccabei (1732 Conti / Lucchini), oratorio

- La madre de’ Maccabei (1737 Porsile / Manzoni), oratorio

- La madre de' Maccabei (1745 Mazzoni / Belletti), oratorio

- (++) Judas Maccabeus (1747 Haendel / Morell), oratorio

- Alexander Balus (1748 Haendel / Morell), oratorio

- Martyrdom of the Seven Maccabean Brothers (1759 Tiepolo), art

- Spartacus (1760 Saurin), play

- Antiochus der wütente Tyrann, und Vorbild des künftigen Antichrist (Antiochus the Raging Tyrant and Figure of the Future Antichrist / 1762 Werner), oratorio

- La madre de' Maccabei (The Mother of the Maccabean Martyrs / 1763 Petrucci), oratorio

- La madre de' Maccabei (1764 Barbieri), libretto

- La madre de' Maccabei (1764 Guglielmi / Barbieri), oratorio

- La madre de' Maccabei (1765 Anfossi / Barbieri), oratorio

- La madre de' Maccabei (1765 Garroni / Barbieri), oratorio

- Matatia (Matthatias / 1765 Nenci / Coltellini), oratorio

- La madre de' Maccabei (1767 Bergamini / Barbieri), oratorio

- Colección de varias historias (1767-1768 Santos Alonso), novel

- Machabaeorum mater (The Mother of the Maccabean Martyrs / 1770 Sacchini / Chiari), oratorio

- La madre de' Maccabei (1775 Gatti / Barbieri), oratorio

- Les macchabées (The Maccabees / 1780 Deshayes), oratorio

- Salome, madre de' sette martiri Maccabei (1783 Silva / Martinelli), oratorio

- Antioco (Antiochus / 1787 Gabellone), oratorio

- Heliodorus Driven out of the Temple (1791 Thorvaldsen), art

- Spartaco (Spartacus / 1793 Batini, Puccini A., Puccini D. / Vannucci), opera

- Spartakus (Spartacus / 1793 Meissner), novel

- Gionata Maccabeo (1798 Guglielmi), opera

- Judas Machabée; ou, Le rétablissement du culte à Jérusalem (1803 Massillian), play

- Thirza und ihre sieben Söhne (Thirza and Her Seven Sons / 1806 Rieger / Niemeyer), oratorio

- Les Machabées; ou, La prise de Jérusalem (1817 Cuvelier de Trie), play

- Die Makkabäer; oder, Salomomäa und ihre Söhne (1818 Seyfried), opera

- I sette Maccabei (1818 Trento / Tarducci), opera

- Giuda Maccabeo; ossia, La morte di Nicanore (1819 Crispi / Rasi), oratorio

- Helons Wallfahrt nach Jerusalem (Helon's Pilgrimage to Jerusalem / 1820 Strauss), novel

- Die Mutter der Makkabäer (1820 Werner), play

- Giuda Maccabeo; ossia, La morte di Nicanore (1821 Basili), oratorio

- Les Machabées (1822 Guiraud), play

- Spartacus (1822 Moodie), juvenile novel

- Helon’s Pilgrimage to Jerusalem (1825 @1820 Strauss / Kenrich), novel (English ed.)

- Zillah (1828 Smith), novel

- Spartacus (1830 Foyatier), art

- The Five Books of Maccabees in English (1832 Cotton), book

- Die Makabäer (The Maccabees / 1838 Stahlknecht), oratorio

- Iddo (1841 Anonymous), children's novel

- Die Makkabäer (1842 Gutzkow), play

- Martyrdom of the Seven Maccabean Brothers (1842 Stattler), art

- Die Makkabäer (The Maccabees / 1842 Tarnowski), novel (German)

- Spartacus (1847 Vela), art

- Eleazzaro; o, I Maccabei (1848 Biagi), opera

- Die Makkabäer (1852 Ludwig), play

- Das erste Buch der Maccabäer (1853 Grimm), book

- Matatia (Matthatias / 1853 Liberali / Vicoli), oratorio

- The First of the Maccabees (1855 Wise), novel

- Die Hasmonäer (1856 Michaël), play

- Das zweite, dritte und vierte Buch der Maccabäer (1857 Grimm), book

- Giuda Maccabeo (1859 Mariotti / Meini), oratorio

- Die Hasmonäer (1859 Stein), play

- Expulsion of Heliodorus from the Temple (1861 Delacroix), art

- Martyrdom of the Seven Maccabean Brothers (1863 Ciseri), art

- Judas Makkabäus (1865 Bolander), novel

- Matatia vincitore (Matthatias Triumphant / 1865 Coppola), oratorio

- The History of Antiochus Epiphanes; or, The Institution of the Feast of Dedication (1866 Rajpurkar), book

- Hebrew Heroes (1869 Tucker), children's novel

- The Oath of Spartacus (1871 Barrias), art

- Judas Maccabaeus (1872 Longfellow), play

- Die Makkabäer (The Maccabees / 1873 Rubinstein / Mosenthal), opera

- Johann Hyrkan (1877 Werner), book

- The Cursed Field (1878 Bronnikov), art

- Judas Maccabaeus and the Jewish War of Independence (1879 Conder), book

- Judas Maccabäus (1879 Zopff), opera

- Histoire des Machabées; ou, Princes de la dynastie asmonéenne (1880 Saulcy), book

- Helon of Alexandria: A Tale of Israel in the Time of the Maccabees (1884 @1820 Strauss / Saphir), novel (English ed.)

- The Feast of Light (1885 Bien), play

- Hanike (1889 Lerner), play

- The Hammer (1890 Church), children's novel

- Judas Maccabaeus (1892 Goldfaden), play

- Some Jewish Women (1892 Zirndorf), book

- The Fourth Book of Maccabees and Kindred Documents in Syriac (1895 Bensly/Barnes), book

- The First Book of Maccabees (1897 Fairweather, Black), book

- Alexander Jannaeus (1897 Landau), play

- Judas Maccabaeus (1898 Mendes), children's play

- The Age of the Maccabees (1898 Streane), book

- Aleksander Yanai, der fershtosener prints (1898 Ter), play

- The Patriots of Palestine (1898 Yonge), novel

- Haus Hasmonai (1900 Christ), novel

- The Maccabees March (1901 Cook), music

- Deborah (1901 Ludlow), novel

- Hannah and Her Seven Sons (1902 Louis), poetry

- For Liberty (1903 Jacobson), children's play

- Commentarius in duos libros Machabaeorum (1907 Knabenbauer), book

- Spartaco (Spartacus / 1909 Gherardini), short film

- I Maccabei (The Maccabees / 1911 Guazzoni), short film

- Jewish History and Literature under the Maccabees and Herod (1913 Alford), book

- Spartaco (Spartacus / 1913 Vidali), feature film

- Juda Makabé (Judas Maccabeus / 1914 Fishta), play

- Onder het veldteeken der Makkabeërs (1914 Penning), novel

- Rom und die Hasmonäer (1914 Roth), book

- The Maccabees (1918 Freed), play

- Juda Makkabäus (1919 Sandow), opera

- Das erste Buch der Machabäer (1920 Gutberlet), book

- Prime linee di storia della tradizione maccabaica (1930 Momigliano), book

- Modin Women (1931 Goller), play

- Giuda Maccabeo (Judas Maccabee / 1931 Quercetti / Recanatesi), opera (music & libretto)

- (+) Der Gott der Makkabäer (The God of the Maccabees / 1937 Bickerman), book

- Passio ss. Machabaeorum (1938 Dörrie), book

- Judas Makkabäus (1943 Boxler), novel

- Die Politik Antiochos' des IV (1943 Jansen), book

- Les Macchabées (1945 Ludwig / Mis), play (French ed.)

- Les livres des Maccabées (1949 Abel), book

- The First Book of Maccabees (1950 Tedesche/Zeitlin), book

- Mina ärorika bröder = My Glorious Brothers (1951 Moberg / @1948 Fast), novel (Swedish ed.)

- The Island of the Innocent (1952 Fisher), novel

- Libri dei Maccabei (1952 Penna), book

- The Third and Fourth Books of Maccabees (1953 Hadas), book

- My Glorious Brothers (1953 Vale / Fast), oratorio

- A Commentary on I Maccabees (1954 Dancy), book

- Mis gloriosos hermanos = My Glorious Brothers (1954 @1948 Fast / Calés), novel (Argentine ed.)

- Die Quellen des I. und II. Makkabäerbuches (1954 Schunck), book

- (+) Melekh basar va-dam (The King of Flesh and Blood / 1954 Shamir), novel

- The Second Book of Maccabees (1954 Tedesche/Zeitlin), book

- Hanukkah of the Maccabees (1955 Binder), oratorio

- Judas Macabeo (1958 Aguirre), play

- The King of Flesh and Blood (1958 Shamir / Patterson), novel (English ed.)

- Aleksandrah (1959 Avidom / Ashman), opera

- Il Vecchio Testamento (1963 Parolini), film

- The First and Second Books of the Maccabees (1966 Schoenberg), book

- Grottorna i ökenbergen (1966 Sundgren), novel

- Die Theokratie nach dem 1. und 2. Makkabäerbuch (1967 Arenhoevel), book

- Gloriosii mei frati (My Glorious Brothers / 1967 Fast / Litman-Litani), novel (Romanian ed.)

- The Fifth Book of the Maccabees (1969 Reznikoff), poetry

- Der Topos der Nine Worthies in Literatur und bildender Kunst (The Topos of the Nine Worthies in Literature and Visual Arts / 1971 Schroeder), book

- The First and Second Books of the Maccabees (1973 Bartlett), book

- The First Book of Maccabees (1973 McEleney), book

- The Second Book of Maccabees (1973 McEleney), book

- The Maccabees (1973 Pearlman), non-fiction book

- Moi proslavlennye brat’ia (1975 Fast), novel (Russian ed.)

- Beobachtungen zu Sprache, Stil und Gedankengut des Vierten Makkabäerbuchs (1976 Breitenstein), book

- The Hanukkah Story (1977 Hirsh), children's novel

- Not by Might (1979 Sargon), oratorio

- מלחמות החשמונאים (Judas Maccabaeus: The Jewish Struggle against the Seleucids / 1980 Bar-Kochva), book

- Hikre ha-tekufah ha-Hashmonait (1980 Efron), book

- Temple Propaganda: The Purpose and Character of 2 Maccabees (1981 Doran), book

- La crise maccabéenne (1982 Saulnier), book

- 1-2 Maccabei: lotta e martirio per la fede (1982 Vallauri), book

- Hellenistische Reform und Religionsverfolgung in Judäa (1983 Bringmann), book

- La crisis macabea (1983 Saulnier / Darrícal), book (Spanish ed.)

- Even ha-mizbeah (1984 Baram), novel

- 1 Makkabäer, 2 Makkabäer (1985 Dommershausen), book

- First Maccabees, Second Maccabees (1985 Spilly), book

- Studies on the Hasmonean Period (1987 Efron), book (English ed.)

- The Land of Israel as a Political Concept in Hasmonean Literature (1987 Mendels), book

- The Maccabean Revolt: Anatomy of a Biblical Revolution (1988 Harrington), book

- The Hasideans and the Origin of Pharisaism (1988 Kampen), book

- Judas Maccabaeus: The Jewish Struggle against the Seleucids (1989 @1980 Bar-Kochva), book (English ed.) = מלחמות החשמונאים

- The Hasmonean Revolt: Rebellion or Revolution (1989 Derfler), book

- The Story of Hanukkah (1989 Ehrlich / Sherman), children's novel & art

Media in category "Maccabees (subject)"

The following 9 files are in this category, out of 9 total.

- 1948 * Fast (novel).jpg 375 × 499; 35 KB

- 1956 * Farmer.jpg 568 × 929; 20 KB

- 1962 * Bickerman.jpg 316 × 499; 31 KB

- 1976 Goldstein.jpg 333 × 499; 45 KB

- 1979-T * Bickerman en.jpg 658 × 1,000; 33 KB

- 1983 Goldstein.jpg 317 × 474; 42 KB

- 2012 Doran.jpg 421 × 500; 18 KB

- 2016-E Grabbe Boccaccini.jpg 338 × 499; 29 KB

- 2021-E Berlin.jpg 333 × 499; 29 KB