Category:Muslim-Christian Relations (subject)

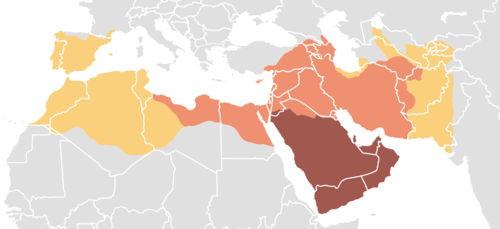

Muslim-Christian dialogue dates back to the rise of Islam in the seventh century. Rooted as both traditions are in the monotheism of the patriarch Abraham, Muslims and Christians share a common heritage. For more than fourteen centuries these communities of faith have been linked by their theological understandings and by geographical proximity. The history of Muslim-Christian interaction includes periods of great tension, hostility, and open war as well as times of uneasy toleration, peaceful coexistence, and cooperation.

The Qur'an

Islamic self-understanding incorporates an awareness of and direct link with the biblical tradition. Muḥammad, his companions, and subsequent generations of Muslims have been guided by the Qurʿān, which they have understood as a continuation and completion of God's revelations to humankind. The Qurʿān speaks of many prophets (anbiyāʿ, singular nabī) and messengers (rusul, sg. rasūl) who functioned as agents of God's revelation. Particular emphasis is laid on the revelations through Moses (the Torah) and Jesus (the Gospel) and their respective communities of faith or “People of the Book” (ahl al-kitāb).

The Qurʿān includes positive affirmations for the People of the Book, including the promise that Jews and Christians who have faith, trust in God and the Last Day, and do what is righteous “shall have their reward” (2:62 and 5:69). The different religious communities are explained as a part of God's plan; if God had so willed, the Qurʿān asserts, humankind would be one community. Diversity among the communities provides a test for people of faith: “Compete with one another in good works. To God you shall all return and He will tell you (the truth) about that which you have been disputing” (5:48).

The Qurʿān states that “there shall be no compulsion in religious matters” (2:256). Peaceful coexistence is affirmed (106:1–6). At the same time, the People of the Book are urged to “come to a common word” on the understanding of the unity of God (tawhīd) and proper worship (e.g., 3:64, 4:171, 5:82, and 29:46). Christians, in particular, are chided for having distorted the revelation of God. Traditional Christian doctrines of the divinity of Jesus and the Trinity are depicted as compromising the unity and transcendence of God (e.g., 5:72–75, 5:117, and 112:3). There are also verses urging Muslims to fight, under certain circumstances, those who have been given a book but “practice not the religion of truth” (9:29).

Early Christian-Muslim Relations

The hostility between Christianity and Islam depends on the political conflicts that opposed European Nations and Arab countries for the control of the Mediterranean, more than on religious principles.

Islam was born after Christianity and spread in countries where the majority of people were once Christians.

Christianity felt threatened by the spread of Islam. The Mediterranean Sea, that once connected the "Christian" countries, was now the border between "Christianity" and "Islam."

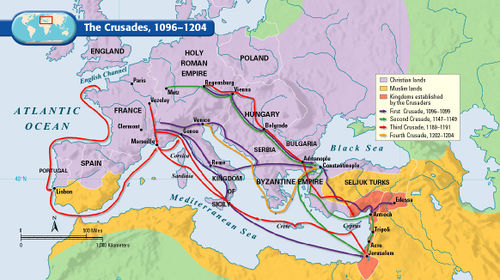

Centuries later, the Crusades were understood by Europeans as a legitimate effort to reconquer lands that once were theirs, while from the Muslim point of view were an invasion of what had now become their own homeland.

Historically, Christians living under Islamic rule were usually treated as “protected [dhimmī] peoples”; the practical implications of dhimmī status fluctuated from time to time and from place to place. Even in the best of circumstances, however, it was difficult for Christians and Muslims to engage one another as equals in dialogue.

With few exceptions, Islamic literature that is focused on Christianity has been polemical. The writings of the celebrated fourteenth-century Muslim scholar Ibn Taymīyah (d. 1328 CE) illustrate the point. In his book Al-jawāb al-ṣaḥīḥ li-man baddala dīn al-masīḥ (The Correct Answer to Those Who Changed the Religion of Christ), Ibn Taymīyah catalogs the major Islamic theological and philosophical criticisms of Christianity: altering the divine revelation, propagating errant doctrine, and grievous mistakes in religious practices.

On the Christian side, the advent of Islam in the seventh century presented major challenges. In the short space of a century, Islam transformed the character and culture of many lands from northern India to Spain, disrupted the unity of the Mediterranean world, and displaced the axis of Christendom to the north. Islam challenged Christian assumptions. Not only were the Muslims successful in their military and political expansion, but their religion presented a puzzling and threatening new intellectual position.

John of Damascus in the eighth century provided the first coherent treatment of Islam. His encounter with Muslims in the Umayyad administrative and military center of Damascus led him to regard Islam not as an alien tradition but as a Christian heresy. Subsequent Christian writers, particularly those not living among Muslims, were even harsher. Most tended to focus on malicious and absurd distortions of the basic tenets of Islam and the character of Muḥammad. This trend is especially evident in Europe following the Crusades.

The Crusades, launched in 1096, cast a long shadow over many centuries. In the midst of their stories of chivalry and fighting for holy causes, medieval writers painted a picture of Islam as a vile religion inspired by the devil or Antichrist. The prevailing sentiment in Europe is illustrated in Dante's Inferno, where a mutilated Muḥammad is depicted as languishing in the depths of Hell because he was “a fomenter of discord and schism.”

In reality, the situation is far more complex. large Christian communities continued to live e and prosper in Muslim countries,

Cairo, known as the “city of a thousand minarets,” is home to al-Azhar, the mosque and university, which has been a bastion of Sunnī orthodoxy through much of Islamic history. Yet, the Coptic Orthodox Christians in Egypt comprise the largest Christian community in the Arabic speaking world. As an Oriental Orthodox church, the Copts have been completely independent of both the Roman Catholic and the Eastern (Greek, Russian, and Serbian) Orthodox churches since the middle of the fifth century.

The mountains of Lebanon provided safe haven for a wide range of religious groups—numerous Catholic, Orthodox, and Protestant Christians, various Sunnī and Shīʿī Muslims, and the Druze—for more than a thousand years. As minority communities threatened by Christian crusaders or Muslim conquerors or more recent colonial powers, inhabitants of Lebanon have coexisted, cooperated and clashed, in many ways.

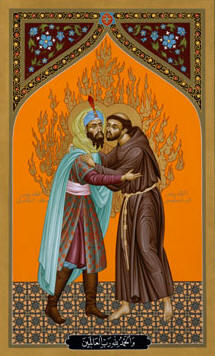

There were a few more positive voices among medieval Christians. St. Francis of Assisi (d. 1226), who in 1219 visited the sultan of Egypt in the midst of the Crusades, instructed his brothers to live among Muslims in peace, avoiding quarrels and disputes. Deep animosity toward Islam was pervasive, however. Martin Luther (d. 1546) wrote several treatises attacking Islam, the Qurʿān, and Muḥammad, motivated in part by the threat of Ottoman Turks advancing on Europe.

Even among the two sides of the Mediterranean some dialogue occurred. Philosophers like Nicolaus Cusanus or Giovanni Pico della Mirandola called for dialogue and peaceful coexistence between Christians and Muslim

Colonialism and the Rise of Arab Nationalism

Several developments in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries set the stage for contemporary Muslim-Christian dialogue.

First, constantly improving transportation and communication facilitated international commerce and unprecedented levels of migration.

Second, scholars gathered a wealth of information on diverse religious practices and belief systems. Although Western studies of Islam were often far from objective, significant changes have occurred. With more accurate information in hand, many non-Muslim scholars concluded that Muḥammad was sincere and devout, challenging the prevailing Western view that he was a shrewd and sinister charlatan. Similarly, the scope and reliability of information on Christianity has broadened the horizons of many Muslim scholars during the past century.

Third, for the first time “parliamentary dialogue” was carried on by the large assemblies convened for interfaith discussion. The earliest example was the 1893 World's Parliament of Religions in Chicago. Islam was represented by Mohammed Alexander Russell Webb. Such gatherings became more frequent in the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries under the auspices of multifaith organizations such as the World Conference on Religion and Peace and the World Congress of Faiths. These sessions tend to focus on better cooperation among religious groups and the challenges of peace for people of faith.

A fourth and final major factor contributing to the new context arose from the modern missionary movement among Western Christians. The experience of personal contact with Muslims and other people of faith led many missionaries to reassess their presuppositions. Participants in the three twentieth-century world missionary conferences (Edinburgh in 1910, Jerusalem in 1928, and Tambaram [India] in 1938) wrestled with questions of witness and service in the midst of religious diversity. These conferences stimulated debate and paved the way for ecumenical efforts at interfaith understanding under the auspices of the World Council of Churches (WCC), founded in 1948.

Kahlil Gibran, "Jesus, the Son of Man"

The Muslim Presence in Europe and the United States

The dialogue movement began during the 1950s when the WCC and the Vatican organized a number of meetings between Christian leaders and representatives of other religious traditions. These initial efforts resulted in the formation of new institutions. In 1964, toward the end of the Second Ecumenical Council of the Vatican (Vatican II), Pope Paul VI established a Secretariat for Non-Christian Religions to study religious traditions, provide resources, and promote interreligious dialogue through education and by facilitating local efforts by Catholics. Several major documents adopted at Vatican II (1962–1965) focused on interfaith relations, in particular "Nostra Aetate" (1965):

- "The Church regards with esteem also the Moslems. They adore the one God, living and subsisting in Himself; merciful and all- powerful, the Creator of heaven and earth,(5) who has spoken to men; they take pains to submit wholeheartedly to even His inscrutable decrees, just as Abraham, with whom the faith of Islam takes pleasure in linking itself, submitted to God. Though they do not acknowledge Jesus as God, they revere Him as a prophet. They also honor Mary, His virgin Mother; at times they even call on her with devotion. In addition, they await the day of judgment when God will render their deserts to all those who have been raised up from the dead. Finally, they value the moral life and worship God especially through prayer, almsgiving and fasting. Since in the course of centuries not a few quarrels and hostilities have arisen between Christians and Moslems, this sacred synod urges all to forget the past and to work sincerely for mutual understanding and to preserve as well as to promote together for the benefit of all mankind social justice and moral welfare, as well as peace and freedom."

The most visible Christian leader during the last quarter of the twentieth century, Pope John Paul II, was a strong advocate for the new approach to interfaith relations. During his papacy (1978–2005), John Paul II traveled to 117 countries. He often met with leaders from various religions, on his travels and in Rome. He was the first pope to visit a mosque (in Damascus in 2001). The spirit of his approach to Islam is evident in a 1985 speech delivered to over 80,000 Muslims at a soccer stadium in Casablanca:

- "We believe in the same God, the one God, the Living God who created the world … In a world which desires unity and peace, but experiences a thousand tensions and conflicts, should not believers come together? Dialogue between Christians and Muslims is today more urgent than ever. It flows from fidelity to God. Too often in the past, we have opposed each other in polemics and wars. I believe that today God invites us to change old practices. We must respect each other and we must stimulate each other in good works on the path to righteousness."

In 1989, John Paul II reorganized the Secretariat for Non-Christian Religions and renamed it the Pontifical Council for Interreligious Dialogue.

The WCC established its program for Dialogue with People of Living Faiths and Ideologies (DFI) in 1971: Muslim-Christian relations were a primary focus from the outset. In cooperation with more than three hundred WCC member churches, the DFI concentrated on organizing large international and smaller regional meetings and on providing educational materials. The WCC and Vatican publish books, articles, reports, working papers, and reviews by both Christians and Muslims.

By the 1980s and 1990s, other international organizations developed formal and informal programs for Muslim-Christian dialogue. The Muslim World League, the World Muslim Congress, and the Middle East Council of Churches are notable examples.

At the local level, hundreds of interfaith organizations have facilitated dialogue programs. These programs are difficult to characterize because they vary substantially. Detailed information and analyses of activities in specific countries and organizations is accessible through the periodicals listed in the bibliography; the following examples illustrate the breadth of activity.

In India and the Philippines, Christian institutions have studied Islam and pursued dialogue programs for decades. These academic programs stimulated particular initiatives by churches and Muslim organizations. Muslim-Christian dialogue programs can also be found in Nigeria, Indonesia, Tunisia, France, Tanzania, and elsewhere.

The Muslim community in Great Britain numbers well over two million. The large influx of Muslims since 1950 has spawned numerous local and national Islamic organizations, many of which are engaged with Christian counterparts in local churches or through programs of the British Council of Churches. Their concerns range from education and health care to the resolution of Middle East conflicts.

The Islamic presence increased also in the United States after WW2. The Islamic Center of Washington opened in 1957. In addition to numerous dialogue programs organized by local interfaith organizations or state councils of churches, two major academic centers in the U.S. provide leadership and programs centered on Muslim-Christian relations. For over fifty years, Hartford Seminary in Connecticut has specialized in the study of Islam and Muslim-Christian relations through degree programs, continuing education, and publications.

The Center for Muslim-Christian Understanding (CMCU) was founded at Georgetown University in 1993. Through research, publications, academic and community programs, the center seeks to improve relations between the Muslim world and the West as well as enhance understanding of Muslims in the West. In 2005, the CMCU received a $20 million gift from Prince Alwaleed Bin Talal of Saudi Arabia in order to strengthen and expand its many programs; its full name is now Prince Alwaleed Bin Talal Center for Muslim-Christian Understanding.

Globalization and anti-Globalization

The process of post-colonianism created strong anti-Western attitudes in some Muslim countries, but initially, it did not affect Christian-Muslim relations as religion was not involved, and nationalistic movements were secular

The Islamic revolution in Iran in 1979 changed the situation. For the first time religion became part of the political debate and nationalism took a religious form.

At the same time Global economy has favored mass migration in Europe and the United States. Today, around 20 million Muslims (or around 5%) live in the European Union, and around 3.5 million Muslims (or around 1%) live in the United States.

The September 11, 2001 attacks on the World Trade Center in New York and the Pentagon in Washington marked a major turning point in Muslim-Christian relations. These and many subsequent developments in the U.S., Afghanistan, Iraq, Iran, Lebanon, and Israel/Palestine created both obstacles and opportunities for Muslim-Christian dialogue.

This has caused the rise of anti-Muslim attitudes in Europe and the United States, but also a greater awareness about the close relations between Christians and Muslims

Anti Muslim Harassment - What Would You Do?

But it has also caused a renewed effort to promote better relations. In the U.S., thousands of churches focused study programs on Islam; many initiated dialogue programs and constructive projects (e.g., churches, mosques and synagogues together building houses for low-income neighbors). Courses on Islam and interfaith relations increased dramatically in colleges and universities throughout North America. The concerted efforts to facilitate constructive dialogue during the previous half century provided an invaluable foundation for many.

Muslim-Christian dialogue represents a new and major effort to understand and cooperate with others in increasingly interdependent and religiously diverse countries. The newness of dialogue and the absence of conceptual clarity have required experimentation. Questions about planning, organization, representation, and topics need thoughtful consideration and careful collaboration. Through trial and error, advocates of interfaith dialogue in Asia, Africa, Europe, and North America continue to refine the process. Many local, regional, and international dialogue groups have developed guidelines to address common concerns and avoid pitfalls. Many of these resources are readily available on the Internet.

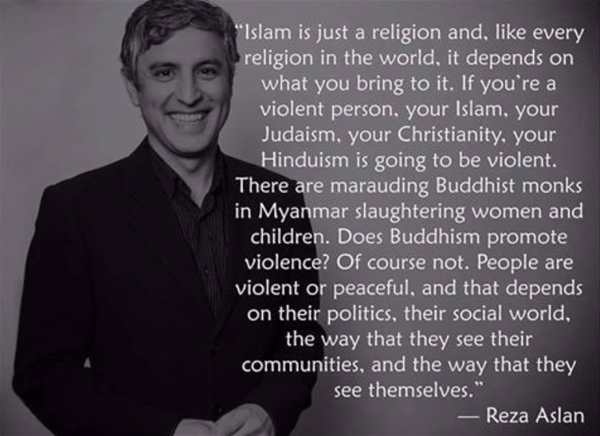

Some Muslim scholars, notably Tarif Khadili e Reza Aslan, are now directly involved in the research on the historical Jesus. See Muslim Jesus, and The Muslim Jesus: Sayings and Stories in Islamic Literature (2001 Khalidi), book.

Bibliography

- Brown, Stuart E., comp.Meeting in Faith: Twenty Years of Christian-Muslim Conversations Sponsored by the World Council of Churches. Geneva: WCC Publications, 1989. Helpful overview of the first two decades of WCC programs.

- Centre for the Study of Islam and Christian-Muslim Relations, Research Papers. Birmingham, UK, 1975–. Series sponsored by the Centre, and a primary source for contemporary research and reflection. Other Centre publications focus on Europe and Africa.

- Cragg, Kenneth. The Call of the Minaret. 2d rev. ed.Maryknoll, N.Y.: Orbis, 1985. First published 1956. Groundbreaking book challenging Christians to take Islam seriously and on its own terms.

- Current Dialogue. Geneva, 1980–. Publication of the World Council of Churches, featuring articles, reports, reviews, and bibliographies.

- Encounter: Documents for Muslim-Christian Understanding. Rome, 1965–. Publication of the Pontifical Council for Interreligious Dialogue.

- Haddad, Yvonne Yazbeck, and Wadi Z. Haddad, eds.Christian-Muslim Encounters. Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 1995. An invaluable collection of twenty-eight articles exploring scriptural, theological, historical, and contemporary dimensions of Christian-Muslim relations.

- Ibn Taymīyah, Aḥmad. A Muslim Theologian's Response to Christianity, ed. and trans. by Thomas Michel. Delmar N.Y.: Caravan Books, 1984.

- Islam and Christian-Muslim Relations. Birmingham, U.K., and Washington, D.C.1990–. Quarterly journal covering a wide range of historical and contemporary aspects of Christian-Muslim issues.

- Islamochristiana. Rome, 1975–. Scholarly annual journal produced by the Pontifico Instituto di Studi Arabi e d’Islamistica. Articles, notices, and reviews are in English, French, and Arabic.

- Mohammed, Ovey N.Muslim-Christian Relations: Past, Present, Future. Maryknoll, N.Y.: Orbis, 1999. Brief, accessible introduction to Islam and to the theological obstacles and opportunities in dialogue.

- The Muslim World. Hartford, Conn., 1911–. Indispensable quarterly journal devoted to the study of Islam and Christian-Muslim relations past and present.

- Sherwin, Byron L, and Harold Kasimow, eds.John Paul II and Interreligious Dialogue. Maryknoll, N.Y.: Orbis, 1999. Accessible collection of John Paul II's teachings on and others’ responses to his views on interfaith dialogue, Islam, Judaism, and Buddhism.

- Southern, R. W.Western Views of Islam in the Middle Ages. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1962. Highly readable and instructive survey by a noted historian.

- Watt, W. Montgomery. Muslim-Christian Encounters. London: Routledge, 1991. Reflections by a prominent Christian scholar of Islam.

Related categories

Pages in category "Muslim-Christian Relations (subject)"

The following 41 pages are in this category, out of 41 total.

1

- Compendium historicum eorum quae Muhammedani de Christo et praecipuis aliquot religionis Christianae capitibus tradiderunt (1643 Warner), book

- Muhammedanische Studien (Muslim Studies / 1889-1890 Goldziher), book

- The Bible and Islam; or, The Influence of the Old and New Testaments on the Religion of Mohammed (1897 Smith), book

- Die Anhängigkeit des Korans von Judentum und Christentum (The Dependence of the Qur'an on Judaism and Christianity / 1922 Rudolph), book

- Le credenze religiose di Maometto (The Religious Beliefs of Muhammad / 1922 Sacco), book

- Der Ursprung des Islams und das Christentum (Christianity ad the Origins of Islam / 1926 Andræ), book

- The Origin of Islam in Its Christian Environment (1926 Bell), book

- Jüdische und christliche Lehren im vor- und frühislamischen Arabien (Jewish and Christian Teachings in Pre- and Early Islamic Arabia / 1939 Hirschberg), book

- Le Coran et la révélation judéo-chrétienne (The Qur'an and the Jewish and Christian Revelations / 1958 Masson), book

- Muslim Theology: A Study of Origins with Reference to the Church Fathers (1964 Seale), book

- The Termination of Hostilities in the Early Arab Conquest (1971 Hill), book

- John of Damascus on Islam: The "Heresy of the Ishmaelites" (1972 Sahas), book

- Über den Ur-Qur'an (Reconstructing The Ur-Qur'an / 1974 Lüling), book

- Temple et contemplation (Temple and Contemplation / 1980 Corbin), book

- Trois messagers pour un seul Dieu (Three Messengers for One God / 1983 Arnaldez), book

- Die theologische Beziehungen des Islams zu Judentum und Christentum (Islam, Judaism, and Christianity: Theological and Historical Affiliations / 1988 Busse), book

- Early Islam: Collected Articles (1990 Watt), book

- Qur'anic Christians: An Analysis of Classical and Modern Exegesis (1991 McAuliffe), book

- The Byzantine and Early Islamic Near East (1992 Cameron, Conrad, King), edited volume

- Anti-Christian Polemic in Early Islam: Abu 'Isa Al-Warraq's 'Against the Trinity' (1992 Thomas), book

- Arabs and Others in Early Islam (1997 Bashear), book

- Seeing Islam as Others Saw It: A Survey and Evaluation of Christian, Jewish and Zoroastrian Writings on Early Islam (1997 Hoyland), book

- Jihad: The Origin of Holy War in Islam (1999 Firestone), book

- The Idea of Idolatry and the Emergence of Islam: From Polemic to History (1999 Hawting), book

- I profeti biblici nella tradizione islamica (Biblical Prophets in the Qur'an and Muslim Literature / 1999 Tottoli), book

2

- Islamic Christianity: An Account of References to Christianity in the Quran (2000 Gohari), book

- Die Syro-Aramäische Lesart des Koran (2000 Luxenberg), book

- Syrian Christians under Islam: The First Thousand Years (2001 Thomas), edited volume

- Studies in Muslim Apocalyptic (2002 Cook), book

- Arab-Byzantine Relations in Early Islamic Times (2004 Bonner), book

- Le messie et son prophète (The Messiah and His Prophet / 2005 Gallez), book

- The Encounter of Eastern Christianity with Early Islam (2006 Grypeou, Swanson, Thomas), edited volume

- Defending the People of Truth in the Early Islamic Times: The Apologies of Abu Ra'itah (2006 Keating), book

- Christian Doctrines in Islamic Theology (2008 Thomas), book

- Abraham in Judentum, Christentum und Islam (Abraham in Judaism, Christianity, and Islam / 2009 Böttrich, Ego, Eissler), edited volume

- The Legend of Sergius Bahira: Eastern Christian Apologetics and Apocalyptic in Response to Islam (2009 Roggema), book

- Christian-Muslim Relations: A Bibliographical History 1, 600-900 (2009 Thomas, Roggema), edited volume

- Gog and Magog in Early Eastern Christian and Islamic Sources (2009 van Donzel, Schmidt), book

- Non-Muslims in the Early Islamic Empire: From Surrender to Coexistence (2011 Levy-Rubin), book

- Three Testaments: Torah, Gospel, and Quran (2012 Brown), edited volume

- The Coming of the Comforter: When, Where, and to Whom? (2012 Segovia, Lourié), edited volume

Media in category "Muslim-Christian Relations (subject)"

The following 3 files are in this category, out of 3 total.

- 1965 * Parrinder.jpg 326 × 499; 34 KB

- 1985 * Cragg.jpg 647 × 1,000; 50 KB

- 2010 Leirvik.jpg 333 × 499; 22 KB