Difference between revisions of "Category:Holocaust Children's Diaries (subject)"

(→2007) |

|||

| Line 2: | Line 2: | ||

* [[Children in the Holocaust]] -- [[Holocaust Children's Memoirs]] -- [[Holocaust Children's Movies]] | * [[Children in the Holocaust]] -- [[Holocaust Children's Memoirs]] -- [[Holocaust Children's Movies]] | ||

There are more than 60 diaries written by Holocaust victims or survivors during the years of persecution. Some of them have been published, the others are available to specialists. In these accounts, the young writers documented their experiences, confided their feelings, and reflected on the trauma they endured during these nightmare years. | |||

"Young journal writers of this period came from all walks of life. Some child diarists came from poor or peasant families. Others were born to middle-class professionals. Some grew up in wealth and privilege. A handful came from deeply religious families, while others grew up in an assimilated and secular community. A majority of child diarists, however, identified with Jewish tradition and culture regardless of their degree of personal faith. Child diaries and journals from the Holocaust era can be grouped into three broad categories: | |||

*Those written by children who escaped German-controlled territory and became refugees or partisans; | |||

*Those written by children living in hiding; and | |||

*Those maintained by young people as ghetto residents, as persons living under other restrictions imposed by German authorities, or, more rarely, as concentration camp prisoners."--USHMM Holocaust Encyclopedia. | |||

See [https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/article/childrens-diaries-during-the-holocaust Children's Diaries during the Holocaust] | |||

== 1940s == | == 1940s == | ||

Revision as of 08:49, 20 January 2020

Holocaust Children's Diaries

There are more than 60 diaries written by Holocaust victims or survivors during the years of persecution. Some of them have been published, the others are available to specialists. In these accounts, the young writers documented their experiences, confided their feelings, and reflected on the trauma they endured during these nightmare years.

"Young journal writers of this period came from all walks of life. Some child diarists came from poor or peasant families. Others were born to middle-class professionals. Some grew up in wealth and privilege. A handful came from deeply religious families, while others grew up in an assimilated and secular community. A majority of child diarists, however, identified with Jewish tradition and culture regardless of their degree of personal faith. Child diaries and journals from the Holocaust era can be grouped into three broad categories:

- Those written by children who escaped German-controlled territory and became refugees or partisans;

- Those written by children living in hiding; and

- Those maintained by young people as ghetto residents, as persons living under other restrictions imposed by German authorities, or, more rarely, as concentration camp prisoners."--USHMM Holocaust Encyclopedia.

See Children's Diaries during the Holocaust

1940s

1943

Brundibar (Naxos, 2006) is an opera written in 1944 by composer Hans Krása and librettist Adolf Hoffmeister to be performed by the children of the Terezin Concentration Camp.

Aninka [in English Annette] and Pepíček (Little Joe) are a fatherless sister and brother. Their mother is ill, and the doctor tells them she needs milk to recover. But they have no money. They decide to sing in the marketplace to raise the needed money. But the evil organ grinder Brundibár (of this figure Iván Fischer has said, "Everyone knew he represented Hitler"[5]) chases them away. However, with the help of a fearless sparrow, keen cat, and wise dog, and the children of the town, they are able to chase Brundibár away, and sing in the market square.

On 23 September 1943, Brundibár premiered in Theresienstadt. The production was directed by Zelenka and choreographed by Camilla Rosenbaum, and was shown 55 times in the following year. A special performance of Brundibár was staged in 1944 for representatives of the Red Cross who came to inspect living conditions in the camp, and was filmed for a Nazi propaganda film Theresienstadt: ein Dokumentarfilm aus dem jüdischen Siedlungsgebiet (Theresienstadt: a documentary film from the Jewish settlement area); see YouTube. All of the participants in the Theresienstadt production were herded into cattle trucks and sent to Auschwitz as soon as filming was finished. Most were gassed immediately upon arrival, including the children, the composer Krása, the director Kurt Gerron, and the musicians. Only a few survived.

Here are the names of the children who performed the leading roles in the opera:

- Honza Treichlinger (1930-1944) = Brundibár

- Pintǎ Mühlstein (m.1944) = Pepiček

- Greta Hofmeister Klingsberg (n.1929) = Aninka

- Zdeněk Ohrenstein (1929-1990) = the dog

- Ela Stein Weissberger (1930-2018) = the cat

- Maria Mühlstein (1932-1944) / Stephan Herz-Sommer (1937–2001) = the sparrow

1945

The Diary of Mary Berg: Growing up in the Warsaw Ghetto (1945) is a diary written by Holocaust survivor Mary Berg (Miriam Wattenberg, 1924-2013) in the years 1939-1944 (age 15-19), when living in the Warsaw Ghetto. Published in New York, NY: Fisher, 1945, under the title Warsaw Ghetto: A Diary.

The diary of Miriam Wattenberg (“Mary Berg”) was one of the first children's journals which revealed to a wider public the horrors of the Holocaust.

"Inspiring and fascinating tale of the strength of human spirit during one of humanity’s darkest hours; • Reminiscent of both The Diary of Anne Frank, A Woman in Berlin and Suite Francaise; • Beautifully packaged in an attractive hardback, gift format for the Christmas market and containing original photographs and maps; • A unique insight from one of the few survivors of the Warsaw Ghetto, offering the only contemporary eye-witness account. After 60 years of silence, The Diary of Mary Berg is poised at last to gain the appreciation and widespread attention that it so richly deserves, and is certain to take it’s place alongside The Diary of Anne Frank as one of the most significant memoirs of the twentieth century. From love to tragedy, seamlessly combining the everyday concerns of a growing teenager with a unique commentary on life in one of the darkest contexts of history. This is a work remarkable for its authenticity, detail, and poignancy. But it is not only as a factual report on the life and death of a people that The Diary of Mary Berg ranks with the most noteworthy documents of the Second World War. This is the personal story of a life-loving girl’s encounter with unparalleled human suffering, a uniquely illuminating insight into one of the darkest chapters of history. Mary Berg was imprisoned in the ghetto from 1940 to 1943. Unlike so many others, she survived the war, rescued in a prisoner-of-war exchange due to her mother’s dual Polish-American nationality. Her diary was published in 1945 when she was still only 19, in an attempt to alert the world to the Nazi atrocities in Poland, when it was described as "one of the most heartbreaking documents yet to come out of the war" by the /New Yorker/. After the war, Berg remained in America in quiet anonimity."--Publisher description.

Mary Berg (Miriam Wattenberg, 1924-2013) was born Oct 10, 1924 to a Polish-Jewish father and and American-Jewish mother. They lived in Lódz but fled to Warsaw after the beginning of the war in November 1940. They were soon confined in the Warsaw ghetto. The Wattenbergs survived only because Miriam's mother was a US citizen. In the Summer of 1942 they were detained in the Pawiak prison, shortly before the first large deportation of Warsaw Jews to Treblinka. In January 1943 (three months before the Jewish revolt of the Ghetto) the Wattenbergs were sent to the Vittel internment camp in France, and allowed to emigrate to the United States in March 1944. After the publication of her diary, for a while Mary became a very vocal and popular figure in the anti-Nazi movement. When the war was over, however, Mary decided to live a private live, refusing to participate publicly in any Holocaust-related events, untile her death in April 2013.

1947

The Diary of a Young Girl (1952) is the first English edition of a diary written by Holocaust victim Anne Frank (1929-1945) in 1942-44 (age 13-15), while living in hiding in Amsterdam, Netherlands. First published in the Netherlands (Amsterdam, 1947).

Published in more than 70 languages. Adapted several times to the stage and to the screen.

The Diary of Anne Frank is by far the most famous among the children's diaries of the Holocaust and one of the world's best known books of the twentieth century. It was written in 1942-44, while Anne and her family were in hiding in Amsterdam.

Anne's father, Otto was the only survivor of the Franks. He returned to Amsterdam after the war to find that Anne's diary had been saved by his secretary, Miep Gies, and his efforts led to its publication in 1947. It was translated from its original Dutch version and first published in English in 1952 as The Diary of a Young Girl, and has since been translated into over 70 languages.

"Discovered in the attic in which she spent the last years of her life, Anne Frank’s remarkable diary has become a world classic—a powerful reminder of the horrors of war and an eloquent testament to the human spirit ... In 1942, with the Nazis occupying Holland, a thirteen-year-old Jewish girl and her family fled their home in Amsterdam and went into hiding. For the next two years, until their whereabouts were betrayed to the Gestapo, the Franks and another family lived cloistered in the “Secret Annexe” of an old office building. Cut off from the outside world, they faced hunger, boredom, the constant cruelties of living in confined quarters, and the ever-present threat of discovery and death. In her diary Anne Frank recorded vivid impressions of her experiences during this period. By turns thoughtful, moving, and surprisingly humorous, her account offers a fascinating commentary on human courage and frailty and a compelling self-portrait of a sensitive and spirited young woman whose promise was tragically cut short."--Publisher description.

Anne Frank (1929-1945) was born in Frankfurt, Germany, on June 12, 1929. She lived most of her life in or near Amsterdam, Netherlands, having moved there with her family at the age of four and a half when the Nazis gained control over Germany. In May 1940 Nazi Germany occupied the Netherlands and the persecution began. The Franks lost their German citizenship in 1941 and thus became stateless. As persecutions increased in July 1942, the Franks went into hiding in some concealed rooms behind a bookcase in the building where Anne's father, Otto Frank, worked. They lived there until the family's arrest by the Gestapo in August 1944. Following their arrest, the Franks were transported to concentration camps. In October or November 1944, Anne and her sister, Margot, were transferred from Auschwitz to Bergen-Belsen concentration camp, where they died (probably of typhus) a few months later, probably in February 1945.

1948

The Diary of Éva Heyman (1974) is the first English edition of a diary written by Holocaust victim Éva Heyman (1931-1944) in 1944 (age 13), while living in Hungary under Nazi rule. First published in Hungarian in 1948.

"The diary of Éva Heyman, born in 1931 in Nagyvárad, northern Transylvania (now Oradea, Romania), presented by her mother, Ágnes Zsolt. Her diary covers the period from 13 February (her 13th birthday) to 30 May 1944. At the time of the German occupation in March 1944, Éva was a student at the Jewish school. Her great-grandfather and a great-uncle had been Chief Rabbis of the Neolog Jewish community in the town in the 19th-20th centuries. Éva's parents had divorced, and her mother married the Hungarian Jewish writer Béla Zsolt, who lived in Budapest; Éva remained in Nagyvárad and was raised by her maternal grandparents, the Rácz family. In her diary, she gives a graphic description of the harsh events of the time, both in her home environment and in the city at large. When the ghetto was established in Nagyvárad, Éva's parents, who had been visiting in Nagyvárad, were also interned. They managed to escape from the ghetto to Budapest, where they were rescued on the Kasztner train. Éva, her grandparents, her biological father (Béla Heyman), his mother, as well as other family members were all deported to Auschwitz. Éva arrived in Auschwitz on 6 June, and was gassed on 17 October. Her mother presents here a very brief but heartrending description of Éva's experiences in Auschwitz. At the end, it was Mengele himself who sought her out and put her on the truck to be taken to the gas chamber. Her diary survived because she gave it to the family's cook who came to visit them in the ghetto on 30 May."--Publisher description.

Published in Jerusalem: Yad Vashem, 1974. Originally published in Budapest: Uj Idok Irodalmi Intézet R.T. (Singer és Wolfner), 1948.

Also published in Hebrew, Catalan, French and Italian.

1950s

1959

I Never Saw Another Butterfly: Children's Drawings and Poems from the Terezin Concentration Camp (1959) is the English ed. of an anthology of children's drawings made by children of the Terezin Concentration Camp in the years 1942-1943. Originally published in Czech (1959)

"A selection of children's poems and drawings reflecting their surroundings in Terezín Concentration Camp in Czechoslovakia from 1942 to 1944. Fifteen thousand children under the age of fifteen passed through the Terezin Concentration Camp. Fewer than 100 survived. In these poems and pictures drawn by the young inmates, we see the daily misery of these uprooted children, as well as their hopes and fears, their courage and optimism. 60 color illustrations."--Publisher description.

Published in Praha: Museo Statale Ceco, 1959). Originally published in Czech (Prague: Museo statale ceco, 1959). Reprinted in New York: McGraw-Hill, 1962, and 1978. 2nd enlarged ed. by the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum (New York : Schocken Books, 1993).

Also published in German (1959), French (1959), Hebrew (1963), and other languages

1960s

1960

The Diary of Dawid Rubinowicz (Edinburgh : W. Blackwood, 1981) is the first English edition of a diary written in Polish by Holocaust victim Dawid Rubinowicz (1927-1942) in 1940-42 (age 12-15), while living in Poland under Nazi rule. First published in Poland (Warszawa : Ksiazka i Wiedza, 1960).

"Dawid Rubinowicz began his diary in March 1940, after the Nazi invasion, and continued until at least June 1942. He left his diary, written in at least five copybooks, with his Polish neighbor and friend, Tadeusz Waciński. Later, the notebooks were passed on to Antoni Waciński, who kept them in his house for 15 years. A family that rented the house in the 1950s found the diary and read it aloud on the local radio. A few years later, journalist Maria Jarochowska arranged for it to be published for the first time. Excerpts from Dawid's diary also appear in several anthologies, including Salvaged Pages: Young Writers’ Diaries of the Holocaust, edited by Alexandra Zapruder and We Are Witnesses: Five Diaries of Teenagers Who Died in the Holocaust, edited by Jacob Boas."--Publisher description.

Also published in German, Hungarian, Hebrew, French, Dutch, Italian, Japanese, Slovak, Spanish, Swedish, Ukrainian, Norwegian, Danish, Russian, Yiddish.

Dawid Rubinowicz (1927-1942) was born and raised in Krajno, Poland, the son of a poor Jewish diary farmer. Dawid and his entire family perished in the Nazi gas chambers at Treblinka. Dawid was only 15 when he died.

1965

Young Moshe's Diary: The Spiritual Torment of a Jewish Boy in Nazi Europe (1965) is the English ed. of a diary written by Holocaust victim Moshe Flinker (1926-1944) in the years 1942-1943 (age 15-17), when living in hiding in Brussels, Belgium with his family.

"Moshe Flinker died in Auschwitz but he left copy books describing his innermost thoughts during the fateful days prior to his deportation. His surviving sisters rescued his writings from the cellar of the house in which they had all hid. In his unnatural underground existence he did not fully realize the methodical extermination being perpetrated by the Nazis, but he came very near in a remarkable portrayal of the Jewish situation, which he recorded in January 1943."--Publisher description.

"Moshe Flinker was a sixteen-year-old Jewish boy whose family had fled from Holland to Belgium in an attempt to avoid deportation to the east. During this period of hiding and flight, Moshe was no longer able to go to school or to engage in the activities of normal life. In an attempt to stave off idleness, he decided to begin a diary. Moshe used his diary to record the experiences that his family faced in their struggle to endure Nazi persecution. He also wrestled continuously with the question of why this suffering plagued the Jewish people. On November 30, 1942 he wrote, “Now I return to the question mentioned above and its solution: what can God mean by all that is befalling us and by not preventing it from happening? This raises a further question, which must be settled before we can proceed further with the main problem. This second question is whether our distress is part of the anguish that has afflicted the Jewish people since the exile, or whether this is different than all that has occurred in the past. I incline to the second answer, for I find it very hard to believe that what we are going through today is only a mere link in a long chain of suffering.” Moshe was a deeply religious young man and he sought to understand his present circumstances in the light of biblical history. He looked for insight from the persecutions of the past and longed for God’s promised redemption of the Jewish people. He believed that this deliverance would come when the conditions were right, both in the severity of persecution and in the responses of the victims. Much of his diary was dedicated to this type of analysis. He concluded his November 30th entry with these words, “I should like to pray to the Lord of Israel that He may fulfill in the near future the prayer: ‘Return us unto thee, O Lord, and we shall return; renew our days as of old.’’--Holocaust Center of Florida.

Published in Jerusalem [Israel]: Yad Vashem, 1965. Originally published in Hebrew (Jerusalem [Israel]: Yad Vashem, 1958).

Also published in Russian, Dutch, German, French, Italian, and Yiddish.

Moshe Flinker (1926-1944) was born in The Hague on October 9, 1926, and was raised in an Orthodox Jewish home. After being subjected to increasingly restrictive anti-Jewish measures following the German occupation of the Netherlands in 1940, the Flinker family fled to Belgium in 1942. In Belgium, Moshe and his family were able to pass as non-Jews with the help of false identity papers and relative anonymity ... Moshe was a deeply religious young boy who grappled with the theological problems posed by the unprecedented persecution of the Jews. He was also a gifted linguist who knew and studied eight languages, including Arabic, which he saw as fundamental to his future life in Palestine ... In April 1944, after being betrayed by a known Belgian Jewish collaborator, Moshe, his mother, and his sisters Esther Malka and Leah, were arrested at their home and deported to Malines. His father, tipped off by a neighbor, prevented Moshe’s four other siblings from going home and arranged for them to find refuge in the Tieffenbrunner orphanage near Antwerp ... Two weeks later, Moshe’s father was caught and sent to Malines, where he found his family. They were all deported to Auschwitz-Birkenau in May 1944. Moshe’s mother, Mindel, was murdered on arrival. Esther Malka and Leah remained in the women’s camp ... Moshe and his father spent several months in Auschwitz-Birkenau before they were transferred to Echterdingen labor camp, where they both contracted typhus. From there, they were sent to Bergen Belsen, where they both succumbed to typhus in January 1945 ... Esther Malka and Leah survived Auschwitz-Birkenau and were reunited with their four siblings in Brussels after the liberation. They all emigrated to Israel.

1968

The Diary of the Vilna Ghetto (1973) is a diary written by Holocaust victim Yitskhok Rudashevski (1927-1943) in the years 1941-43 (age 14-16), when living in the Vilma Ghetto. Originally published in Hebrew in 1968.

Yitskhok Rudashevski wrote a diary from June 1941 to April 1943 which detailed his life and struggles living in the Vilna ghetto. His diary was discovered by his cousin Sore Voloshin, in 1944. His cousin Voloshin fought the German army and the Soviet Union, later returning to the hideout, and found Yitskhok's diary. The diary was published in 1973 in English translation by the Ghetto Fighters' House publisher in Israel.

"This is the diary of one of the "other Anne Franks," teen diarists of the Holocaust who are not nearly as famous as she. Yitskhok Rudashevski was fourteen when he began his diary in Vilna (Vilnius), Lithuania during the Nazi occupation. He was a gifted writer and wrote movingly of how his family and all the other Vilna Jews were confined to a ghetto and the ghetto kept shrinking and shrinking as the Nazis conducted "Aktions" and killed vast numbers of people, usually by machine-gunning them en masse at nearby Ponar. Rudashevski did not survive; he and his family went into hiding, but they were caught and almost all of them were executed. He was fifteen years old when he died. His account of the suffering of the Vilna Jews, and his own struggle to remain human amid the disaster, is well worth reading."--Publisher description.

Published in Tel Aviv [Israel]: Ghetto Fighters' House, 1973. Originally published in Hebrew (Tel Aviv: ha-Kibuts ha-meuhad, 1968).

Also published in French (2016), and Lithuanian/Yiddish (2018).

Yitskhok Rudashevski (1927-1943) was a young Jewish teenager who lived in the Vilna Ghetto in Lithuania during the 1940s. He was shot to death in the Ponary massacre on Oct 1, 1943 during the liquidation of September–October 1943.

1990s

1991

I'm Not Even a Grown-Up: The Diary of Jerzy Feliks Urman (London: Menard Press, 1991) is the English edition of a diary written by Holocaust victim Jerzy Feliks Urman (1932-1943) in 1943 (age 11), when living in hiding with his family in West Ukraine. 2nd ed. Bristol: Shearsman Books, 2016.

"I'M NOT EVEN A GROWN-UP: THE DIARY OF JERZY FELIKS URMAN is edited and translated by Anthony Rudolf, whose second cousin Jerzy committed suicide in West Ukraine in 1943. The editor's introduction and notes attempt to portray the cataclysmic background and foreground to the dramatic and hopeless situation Jerzy found himself in. Rudolf includes a memoir written by Jerzy's mother, Sophie Urman who with her husband survived the war. Rudolf argues that in in circumstances where armed resistance was for the most part impossible or counterproductive, the child's death can be seen as an act of resistance of the noblest and most tragic kind. The diary has joined a growing literature of similar works written in hiding."--Publisher description.

Jerzy Feliks Urman (1932-1943) committed suicide in fear of being captured.

1993

Ruthka: A Diary of War (Brooklyn, NY: Remember, 1993.) is the English edition of a diary written in Polish by Holocaust victim Ruthka Lieblich (1926-1942) at age 13 to 16, when living in a Polish village under Nazi occupation.

""This is the journal of Ruthka Lieblich, a Polish Jew from World War II. She wrote in her diary from age 13 to age 16, at which time she was deported to Auschwitz and gassed. A gentile friend kept the diary after the war and it wound up being published. Ruthka had obvious literary talent and wrote short stories and poetry. She wrote her diary in Polish and occasionally in Hebrew, and she tried her hand at English too. At the beginning of the book there's a translator's preface, an editor's preface and an introduction to add context to the story. You learn about some of the people Ruthka mentions in her diary, and about the fate of her hometown, which was situated not far from Auschwitz. Of the 300 Jewish people living in the village of Andrichow, only 25 survived the war. Two of Ruthka's cousins survived; the rest of her family was killed. At the end of the book there are some letters Ruthka wrote to her friends, as well as her surviving cousins' descriptions of her. She apparently had a chance to go into hiding, but she refused because she didn't want to be separated from her family. Although the subheading is "A Diary of War," I think that's a misnomer. You can almost forget that Ruthka is writing all this in Nazi Europe. She only occasionally mentions the war and Hitler and the persecution of the Jews. Instead, Ruthka concentrates on her relationships with her friends, reflections on what it means to be a Jew, her desire to move to Palestine, and questions about God. She became more intensely religious as the diary went on, although she seems to have remained an "assimilated" (rather than Orthodox or Hassidic) Jew. I think Ruthka's diary has earned its place among the other young people's Holocaust diaries. It would probably be a good companion to the diary of Moshe Flinker, another very religious Jew in Nazi Europe."--Publisher description.

Ruthka Lieblich (1926-1942)

1995 (a)

We Are Witnesses: Five Diaries of Teenagers Who Died in the Holocaust (New York, NY: Henry Holt, 1995) is a collection of a diaries written by children during the Holocaust, edited by Jacob Boas.

"The end of the world will soon be here" / David Rubinowicz -- "Long live youth!" / Yitzhak Rudashevski -- "My name is Harry" / Moshe Flinker -- "I want to live!" / Éva Heyman -- "I must uphold my ideals" / Anne Frank.

"The five diarists in this book did not survive the war. But their words did. Each diary reveals one voice, one teenager coping with the impossible. We see David Rubinowicz struggling against fear and terror. Yitzhak Rudashevski shows us how Jews clung to culture, to learning, and to hope, until there was no hope at all. Moshe Ze'ev Flinker is the voice of religion, constantly seeking answers from God for relentless tragedy. Eva Heyman demonstrates the unquenchable hunger for life that sustained her until the very last moment. And finally, Anne Frank reveals the largest truth they all left for us: Hitler could kill millions, but he could not destroy the human spirit. These stark accounts of how five young people faced the worst of human evil are a testament, and an inspiration, to the best of the human soul."--Publisher description.

1995 (b)

Children in the Holocaust and World War II: Their Secret Diaries (New York, NY: Pocket Books, 1995) is a collection of twenty-three diaries written by children during the Holocaust, edited by Laurel Holliday.

Janine Phillips : Poland, 10 years old -- Ephraim Shtenkler : Poland, 11 years old -- Dirk Van der Heide (pseudonym) : Holland, 12 years old -- Werner Galnik : Germany, 12 years old -- Janina Heshele : Poland, 12 years old -- Helga Weissova-Hoskova : Czechoslovakia, 12 years old -- Dawid Rubinowicz : Poland, 12 years old -- Helga Kinsky-Pollack : Austria, 13 years old -- Eva Heyman : Hungary, 13 years old -- Tamarah Lazerson : Lithuania, 13 years old -- Yitskhok Rudashevski : Lithuania, 14 years old -- Macha Rolnikas : Lithuania, 14 years old -- Charlotte Veresova : Czechoslovakia, 14 years old -- Mary Berg (pseudonym) : Poland, 15 years old -- Ina Konstantinova : Russia, 16 years old -- Moshe Flinker : Belgium, 16 years old -- Joan Wyndham : England, 16 years old -- Hannah Senesh : Hungary and Israel, 17 years old -- Sarah Fishkin : Poland, 17 years old -- Kim Malthe-Bruun : Denmark, 18 years old -- Colin Perry : England, 18 years old -- The unknown brother and sister of Lodz Ghetto : Poland, unknown age and 12 years old.

"An anthology of twenty-three diaries written during the Holocaust by children, some of whom were later murdered by the Nazis ... Children in the Holocaust and World War II is an extraordinary, unprecedented anthology of diaries written by children all across Nazi-occupied Europe and in England ... Twenty-three young people, ages ten through eighteen, recount in vivid detail the horrors they lived through. As powerful as The Diary of Anne Frank and Zlata's Diary, children's experiences are written with an unguarded eloquence that belies their years ... Some of the diarists include: a Hungarian girl, selected by Mengele to be put in a line of prisoners who were tortured and murdered; a Danish Christian boy executed by the Nazis for his partisan work; and a twelve-year-old Dutch boy who lived through the Blitzkrieg in Rotterdam. And many others. These heartbreaking stories paint a harrowing picture of a genocide that will never be forgotten, and a war that shaped many generations to follow."--Publisher description.

1995 (c)

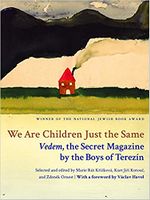

We Are Children Just the Same: Vedem, the Secret Magazine by the Boys of Terezín (Philadelphia : Jewish Publication Society, 1995) is the English ed. of an anthology of articles published by children of the Terezin Concentration Camp in the years 1942-1943. Edited by Marie Rút Krízková, et al. 2nd rev. ed. : Lincoln : University of Nebraska Press, 2012.

"Terezín survivor George (Jirí) Brady recalls: “In the tragic struggle for survival, the Nazi-imposed Terezín ‘self-administration’ tried to help the imprisoned children. They were placed in buildings where living conditions were better than in the many barracks that were inside the fortress. . . . I was one of these children. And by pure luck I found myself among the boys who were led by Valtr Eisinger. In a small room overcrowded with three-tiered bunks, he created a new, fascinating world for us behind the ghetto walls. The boys developed talents they never dreamed they had, and it was there too that the illegal children’s magazine on which this book is based was founded." ... From 1942 to 1944, a group of thirteen- to fifteen-year-old Jewish boys secretly produced a weekly magazine called Vedem (In the Lead) at the model concentration camp, Theresienstadt (“Terezín” in Czech). The writers, artists, and editors put together the issues and copied them by hand behind the blackout shades of their cellblock, which they affectionately called the “Republic of Shkid.” Although the material was saved by one of the handful of boys who survived the Holocaust, it was suppressed for fifty years in Czechoslovakia until 1995, when these works were published simultaneously in English, Czech, and German ... Vedem provides a poignant glimpse into the world of boys torn from their comfortable childhoods and separated from their families, ultimately to perish in the Nazi death machine. The second edition (2012) includes a new preface and epilogue."--Publisher description.

1996

The Diary of Dawid Sierakowiak: Five Notebooks from the Lódz Ghetto (New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 1996) is the English edition of a diary written by Holocaust victim Dawid Sierakowiak (1924-1943) in the years 1939-43, while living with his family in the Lódz Ghetto.

""In the evening I had to prepare food and cook supper, which exhausted me totally. In politics there's absolutely nothing new. Again, out of impatience I feel myself beginning to fall into melancholy. There is really no way out of this for us." This is Dawid Sierakowiak's final diary entry. Soon after writing it, the young author died of tuberculosis, exhaustion, and starvation--the Holocaust syndrome known as "ghetto disease." After the liberation of the /Lod'z Ghetto, his notebooks were found stacked on a cookstove, ready to be burned for heat. Young Sierakowiak was one of more than 60,000 Jews who perished in that notorious urban slave camp, a man-made hell which was the longest surviving concentration of Jews in Nazi Europe ... The diary comprises a remarkable legacy left to humanity by its teenage author. It is one of the most fastidiously detailed accounts ever rendered of modern life in human bondage. Off mountain climbing and studying in southern Poland during the summer of 1939, Dawid begins his diary with a heady enthusiasm to experience life, learn languages, and read great literature. He returns home under the quickly gathering clouds of war. Abruptly /Lod'z is occupied by the Nazis, and the Sierakowiak family is among the city's 200,000 Jews who are soon forced into a sealed ghetto, completely cut off from the outside world. With intimate, undefended prose, the diary's young author begins to describe the relentless horror of their predicament: his daily struggle to obtain food to survive; trying to make reason out of a world gone mad; coping with the plagues of death and deportation. Repeatedly he rallies himself against fear and pessimism, fighting the cold, disease, and exhaustion which finally consume him. Physical pain and emotional woe hold him constantly at the edge of endurance. Hunger tears Dawid's family apart, turning his father into a thief who steals bread from his wife and children ... The wonder of the diary is that every bit of hardship yields wisdom from Dawid's remarkable intellect. Reading it, you become a prisoner with him in the ghetto, and with discomfiting intimacy you begin to experience the incredible process by which the vast majority of the Jews of Europe were annihilated in World War II. Significantly, the youth has no doubt about the consequence of deportation out of the ghetto: "Deportation into lard," he calls it. A committed communist and the unit leader of an underground organization, he crusades for more food for the ghetto's school children. But when invited to pledge his life to a suicide resistance squad, he writes that he cannot become a "professional revolutionary." He owes his strength and life to the care of his family."--Publisher description.

2000s

2002

Salvaged Pages: Young Writers' Diaries of the Holocaust (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2002) is a collection of a diaries written by children during the Holocaust, edited by Alexandra Zapruder.

Klaus Langer (Essen, Germany) -- Elisabeth Kaufmann (Paris, France) -- Peter Feigl (France) -- Moshe Flinker (Brussels, Belgium) -- Otto Wolf (Olomouc, Czechoslovakia) -- Petr Ginz and Eva Ginzova (Terezin Ghetto) -- Yitskhok Rudashevski (Vilna Ghetto) -- Anonymous girl (Lodz Ghetto) -- Miriam Korber (Transnistria) -- Dawid Rubinowicz (Krajno, Poland) -- Elsa Binder (Stanislawow, Poland) -- Ilya Gerber (Kovno Ghetto) -- Anonymous boy (Lodz Ghetto) -- Alice Ehrmann (Terezin Ghetto).

"Presents excerpts from the Holocaust diaries of fifteen young people, ranging in age from twelve to twenty-two, each with an introductory essay that looks at the writer, and the historical context of the diary, with a study of the text and its relevance in the context of Holocaust history or literature. Includes a list of over fifty additional known diaries written by young people during the period."--Publisher description.

Klaus (later Jacob) Langer was born on April 12, 1924, in the city of Gleiwitz in Upper Silesia, which at that time was part of Germany. Klaus, his parents, Erich and Rose, and his grandmother Mina settled in Essen, Germany, in 1936. Klaus was a member of a Zionist youth group and, at times, his membership was a source of conflict with his parents who felt socially, culturally, and nationally German. After Kristallnacht the Langer family desperately attempted to emigrate from Germany, but with each attempt they were met with internal and external obstacles. Klaus escaped Germany on September 2, 1939, eventually settling in Palestine. His parents and grandmother perished in the Holocaust.

Elisabeth Kaufmann was born in 1924 in Vienna. The family fled to France in 1938. when the Nazis invaded France, they had to flee again. Eventually the family moved in 1942 to the United States on one of the last passenger boats to cross the Atlantic during the war.

Peter Ernst Feigl was born on March 1, 1929 in Berlin, Germany. The family moved to Prague, Czech Republic, where they stayed for one year before moving to Vienna, Austria in 1937; fleeing to Brussels, Belgium after the 1938 Anschluss. After his father was arrested he moved with his mother and sister to Paris, France but then traveling to Bordeaux because of the intense Paris bombings. They faced a short internment in Gurs due to his German nationality. He lived in hiding, with false ID until he crossed the border into Switzerland on May 20, 1944 and went into an internment camp. Both his parents perished in Auschwitz. In 1946, immigrating to the United States, where he became a successful businessman.

2005

I'm Still Here: Real Diaries of Young People Who Lived during the Holocaust (2005) is a documentary presenting a collection of a diaries written by children during the Holocaust, edited by Alexandra Zapruder, directed by Lauren Lazin.

Opening -- Diary of Klaus Langer -- Diary of Peter Felgl -- Diary of Elisabeth Kaufmann -- Diary of Dawid Rubinowicz -- Diary of Yitskhok Rudashevski -- Diary of Ilya Gerber -- Diary of Petr and Eva Ginz -- Hitler speech -- Diary of an anonymous girl -- Diary of Miriam Korber -- Diary of Elsa Binder.

"Brings to life the diaries of young people who witnessed first-hand the horrors of the Holocaust. Through an emotional montage of sound and image, the film salutes this group of brave, young writers who refused to quietly disappear. The stories of the young Holocaust victims come to life by weaving together personal photos, handwritten pages and drawings from the diaries, and archival films. Original footage shot in Vilnius, Lithuania, in the remnants of the old Jewish ghetto."--Publisher description.

Published in New York, NY: MTV Networks (distributed by Sisu Home Entertainment), 2008). Available on YouTube (48m).

2006

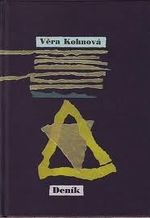

The Diary of Vera Kohnová / Deník Vera Kohnová / Das Tagebuch der Vera Kohnová (Stredokluky : Published by Zdenek Susa, Vimperk [CZ] : Printed by Akcent, 2006) is the trilingual edition (Czech-English-German) of a diary written by Holocaust victim Vera Kohnová (1929-1942) in 1941 (age 12), while living in Czechia under Nazi occupation.

In 1941, at the age of twelve, a Czech Jewish girl, Vera Kohnová, began keeping a diary. She wrote in it for five months, during which time the situation of her family and other Jews in Plzeň gradually worsened. She didn't describe the fate of Jews of the time but wrote mainly about her personal feelings. The last entry in her diary is, "We are here just tomorrow and after tomorrow, who knows what will be then. Bye-bye, my diary!". Although she and her family did not survive, her diary was hidden by Marie Kalivodová and Miroslav Matouš for 65 years.

Vera Kohnová (1929-1942) was born in Plzeň in 1929, into the family of Otakar Kohn, a secretary for the Teller company. As Czech Jews they were persecuted during the Nazi occupation. On 22 January 1942, the family was put on transport "S" to Theresienstadt. The last record of Věra Kohnová comes from 11 March 1942, when she left Theresienstadt on a transport for another Nazi camp in Izbica—a transfer station to the extermination camps.

2007

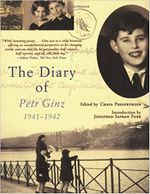

The Diary of Petr Ginz (New York, NY: Atlantic Monthly Press, 2007) is the English edition of a diary written by Holocaust victim Petr Ginz (1928-1944) in 1941-1942 (age 12-14), while living in Prague under Nazi rule, before being deported to Theresienstadt and Auschwitz.

"Lost for sixty years in a Prague attic, the secret diary of a fourteen-year-old prodigy who later died at Auschwitz describes with keen insight into Jewish life the increasing horror of his situation but also reveals a brilliant, droll teenager with a hunger for life."--Publisher description.

Petr Ginz (1928-1944) was, in spite of his young age, one of the most active intellectuals in Theresienstadt and the editor of the journal Vedem. He perished in Auschwitz. His diary was continued by his sister who remained in Theresienstadt until liberation.

2008

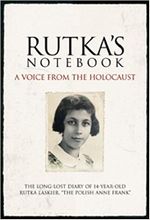

Rutka's Notebook: A Voice from the Holocaust (New York, NY: Time Books, 2008) is the English edition of a diary written by Holocaust victim Rutka Laskier (1929-1943) in January-April 1943 (age 13-14), while living in Poland under Nazi rule.

"More than sixty years after her 1943 death in Auschwitz, the words of fourteen-year-old Rutka Laskier, a young Jewish girl from Bedzin, Poland, offer a poignant study of the everyday lives of Polish Jews caught up in the Holocaust."--Publisher description.

Rutka Laskier (1929-1943)

2010s

2013

Helga's Diary: A Young Girl's Account of Life in a Concentration Camp (New York, NY: W.W. Norton & Company, 2013) is a diary written by Holocaust survivor Helga Weiss (Helga Hošková-Weissová; b.1929), while living in the Theresienstadt ghetto.

"In 1939, Helga Weiss was a young Jewish schoolgirl in Prague. As she endured the first waves of the Nazi invasion, she began to document her experiences in a diary. During her internment at the concentration camp of Terezín, Helga’s uncle hid her diary in a brick wall. Of the 15,000 children brought to Terezín and deported to Auschwitz, there were only one hundred survivors. Helga was one of them. Miraculously, she was able to recover her diary from its hiding place after the war. These pages reveal Helga’s powerful story through her own words and illustrations."--Publisher description.

Helga Weiss (Helga Hošková-Weissová; b.1929)

2014

Rywka's Diary: The Writings of a Jewish Girl from the Lodz Ghetto (San Francisco: Jewish Family and Children's Services, 2014) is the English edition of a diary written in Polish by Holocaust victim Rywka Lipszyc (1929-1945) in the years 1943-44 (age 14), while living in the Lodz Ghetto. New York, NY: Harper, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers, 2015.

"The newly discovered diary of a Polish teenager in the Lodz ghetto during World War II—originally published by Jewish Family & Children’s Services of San Francisco, now available in a revised, illustrated, and beautifully designed trade edition ... After more than seventy years in obscurity, the diary of a teenage girl during the Holocaust has been revealed for the first time. Rywka’s Diary is at once an astonishing historical document and a moving tribute to the many ordinary people whose lives were forever altered by the Holocaust. At its heart, it is the diary of a girl named Rywka Lipszyc who detailed the brutal conditions that Jews in the Lodz ghetto, the second largest in Poland, endured under the Nazis: poverty, hunger and malnutrition, religious oppression, and, in Rywka’s case, the death of her parents and siblings. Handwritten in a school notebook between October 1943 and April 1944, the diary ends literally in mid-sentence. What became of Rywka is a mystery. A Red Army doctor found her notebook in Auschwitz after its liberation in 1945 and took it back with her to the Soviet Union ... Rywka’s Diary is also a moving coming-of-age story, in which a young woman expresses her curiosity about the world and her place in it and reflects on her relationship with God—a remarkable affirmation of her commitment to Judaism and her faith in humanity. Interwoven into this carefully translated diary are photographs, news clippings, maps, and commentary from Holocaust scholars and the girl’s surviving relatives, which provide an in-depth picture of both the conditions of Rywka's life and the mysterious end to her diary ... Moving and illuminating, told by a brave young girl whose strong and charismatic voice speaks for millions, Rywka’s Diary is an extraordinary addition to the history of the Holocaust and World War II."--Publisher description.

Also published in Polish, Spanish, Catalan, Slovak, Czech, French, German, and Hebrew.

Rywka Lipszyc (1929-1945) was a Jewish girl living in the Łódź Ghetto during the Holocaust. Her diary, composed of 112 pages, was written between 3 October 1943 and 12 April 1944 in the Polish language. The exact circumstances of her death are unknown. She survived deportation to Auschwitz-Birkenau concentration camp followed by a transfer to Gross-Rosen and forced labor at its subcamp in Christianstadt. She also survived a death march to Bergen-Belsen, and lived to see her liberation there in April 1945. Too ill to be evacuated, she was transferred to a hospital at Niendorf, where the record of her life ended.

Pages in category "Holocaust Children's Diaries (subject)"

The following 30 pages are in this category, out of 30 total.

1

- Sarah Fishkin (F / Belarus, 1924-1942), Holocaust victim

- Ilya Gerber (F / Lithuania, 1924-1943), Holocaust victim

- Dawid Sierakowiak (M / Poland, 1924-1943), Holocaust victim

- Renia Spiegel (F / Poland, 1924-1942), Holocaust victim

- Moshe Flinker (M / Netherlands, 1926-1944), Holocaust victim

- Clara Kramer (F / Poland, 1927-2018), Holocaust survivor

- Dawid Rubinowicz (Poland, 1927-1942), Holocaust victim

- Yitskhok Rudashevski (M / Lithuania, 1927-1943), Holocaust victim

- Jutta Szmirgeld / Jutta Bergman (Germany, Poland, 1927)

- Otto Wolf (M / Czechia, 1927-1945), Holocaust victim

- Lilly Cohn / Lillyan Rosenberg (F / Germany, 1928), Holocaust survivor

- Vera Diament / Vera Gissing (F / Czechia, 1928), Holocaust survivor

- Leo Silberman (M / Poland, 1928-2015), Holocaust survivor

- Susi Hilsenrath

- Vera Kohnova (F / Czechia, 1929-1942), Holocaust victim

- Rutka Laskier (F / Poland, 1929-1943), Holocaust victim

- Rywka Lipszyc (F / Poland, 1929-1945), Holocaust victim

- Helga Weiss / Helga Hošková-Weissová (F / Czechia, 1929), Holocaust survivor

- Michal Kraus (M / Czechia, 1930), Holocaust survivor

- Éva Heyman (F / Hungary, 1931-1944), Holocaust victim

- Jerzy Feliks Urman (Poland, 1932-1943), Holocaust victim

- I Never Saw Another Butterfly: Children's Drawings and Poems from the Terezin Concentration Camp (1959 @1959 Volavková), anthology

- Ruthka: A Diary of War (1993 Lieblich), book

- Children in the Holocaust and World War II: Their Secret Diaries (1995 Holliday), anthology

- We Are Children Just the Same: Vedem, the Secret Magazine by the Boys of Terezín (1995 Krízková), anthology

- The Diary of Dawid Sierakowiak: Five Notebooks from the Lódz Ghetto (1996 Sierakowiak), book