Difference between revisions of "Category:Enochic Studies--1600s"

| (26 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{| style="margin-top:10px; background:none;" | |||

| style="background:white; width:65%; border:1px solid #a7d7f9; vertical-align:top; color:#000; padding: 5px 10px 10px 8px; -moz-border-radius: 10px; -webkit-border-radius: 10px; border-radius:10px;" | | |||

[[File: | <!-- ===================== COLONNA DI SINISTRA ==================== --> | ||

{| cellpadding="2" cellspacing="5" style="width:100%; vertical-align:top; background:transparent;" | |||

{{WindowMain | |||

|title= [[Enochic Studies]] ([[1600s]]) | |||

|backgroundLogo= Bluebg_rounded_croped.png | |||

|logo= history.png | |||

|px= 38 | |||

|content= [[File:Enoch_Blake.jpg|500px|]] | |||

The page: '''Enochic Studies--1600s''', includes (in chronological order) scholarly and literary works in the field of [[Enochic Studies]], made in the [[1600s|17th century]], or between 1600 and 1699. | |||

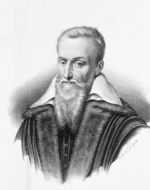

[[File:Joseph Justus Scaliger.jpg|thumb|150px|[[Joseph Justus Scaliger]]]] | |||

[[File:John_Milton.jpg|thumb|150px|[[John Milton]] dictating "Paradise Lost" to his daughters]] | |||

}} | |||

{{WindowMain | |||

|title= Highlights ([[1600s]]) | |||

|backgroundLogo= Bluebg_rounded_croped.png | |||

|logo = contents.png | |||

|px= 38 | |||

|content= | |||

* [[Thesaurus temporum (1606 Scaliger), book]] | |||

}} | |||

{{WindowMain | |||

|title= [[Interpreters]] ([[1600s]]) | |||

|backgroundLogo= Bluebg_rounded_croped.png | |||

|logo = contents.png | |||

|px= 38 | |||

|content= | |||

== | }} | ||

|} | |||

|<!-- SPAZI TRA LE COLONNE --> style="border:5px solid transparent;" | | |||

<!-- ===================== COLONNA DI DESTRA ==================== --> | |||

| style="width:35%; border:1px solid #a7d7f9; background:#f5faff; vertical-align:top; padding: 5px 10px 10px 8px; -moz-border-radius: 10px; -webkit-border-radius: 10px; border-radius:10px;"| | |||

{| id="mp-right" cellpadding="2" cellspacing="5" style="width:100%; vertical-align:top; background:#f5faff; background:transparent;" | |||

{{WindowMain | |||

|title= [[Timeline]] ([[1600s]]) | |||

|backgroundLogo= Bluebg_rounded_croped.png | |||

|logo= history.png | |||

|px= 38 | |||

|content= [[File:1600s.jpg|thumb|left|250px]] | |||

At the beginning of the 17th century, the | '''''[[Enochic Studies]]''''' : [[:Category:Enochic Studies--2020s|2020s]] -- [[:Category:Enochic Studies--2010s|2010s]] -- [[:Category:Enochic Studies--2000s|2000s]] -- [[:Category:Enochic Studies--1990s|1990s]] -- [[:Category:Enochic Studies--1980s|1980s]] -- [[:Category:Enochic Studies--1970s|1970s]] -- [[:Category:Enochic Studies--1960s|1960s]] -- [[:Category:Enochic Studies--1950s|1950s]] -- [[:Category:Enochic Studies--1940s|1940s]] -- [[:Category:Enochic Studies--1930s|1930s]] -- [[:Category:Enochic Studies--1920s|1920s]] -- [[:Category:Enochic Studies--1910s|1910s]] -- [[:Category:Enochic Studies--1900s|1900s]] -- [[:Category:Enochic Studies--1850s|1850s]] -- [[:Category:Enochic Studies--1800s|1800s]] -- [[:Category:Enochic Studies--1700s|1700s]] -- [[:Category:Enochic Studies--1600s|1600s]] -- [[:Category:Enochic Studies--1500s|1500s]] -- [[:Category:Enochic Studies--1450s|1450s]] -- [[Enochic Studies|Home]] | ||

'''''[[Timeline]]''''' : [[2020s]] -- [[2010s]] -- [[2000s]] -- [[1990s]] -- [[1980s]] -- [[1970s]] -- [[1960s]] -- [[1950s]] -- [[1940s]] -- [[1930s]] -- [[1920s]] -- [[1910s]] -- [[1900s]] -- [[1850s]] -- [[1800s]] -- [[1700s]] -- [[1600s]] -- [[1500s]] -- [[1450s]] -- [[Medieval]] -- [[Timeline|Home]] | |||

}} | |||

{{WindowMain | |||

|title= [[Languages]] | |||

|backgroundLogo= Bluebg_rounded_croped.png | |||

|logo= contents.png | |||

|px= 38 | |||

|content= [[File:Languages.jpg|thumb|left|250px]] | |||

'''[[Enochic Studies]]''' : [[:Category:Enochic Studies--English|English]] -- [[:Category:Enochic Studies--French|French]] -- [[:Category:Enochic Studies--German|German]] -- [[:Category:Enochic Studies--Italian|Italian]] -- [[:Category:Enochic Studies--Latin|Latin]] -- [[:Category:Enochic Studies--Spanish|Spanish]] -/- [[Enochic Studies|Other]] | |||

}} | |||

|} | |||

|} | |||

== History of Research ([[1600s]]) -- Notes == | |||

[[File:Peiresc.jpg|thumb|150px|[[Nicolas-Claude Fabri de Peiresc]]]] | |||

[[File:Hiob_Ludolf.jpg|thumb|150px|[[Hiob Ludolf]]]] | |||

At the beginning of the 17th century, scholars shifted their attention from esoteric sources to the Christian chronographical tradition, which until that moment had been largely neglected. In 1601 Italian-French-Dutch scholar Joseph Justus Scaliger located a 11th-century ms of the work of Syncellus in the former library of Catherine de Medici. The Enoch fragments contained in the text were collected by his friend Isaac Casaubon in 1602 at the National Library in Paris, and published by Scaliger in 1606. They were discussed by [[Johannes Drusius]] in 1612 and by [[Jacques Bolduc]] (''De ecclesia ante legem'') in 1626, and translated into English by [[Samuel Purchas]] in 1613. In 1652 [[Jacques Goar]] published the editio princeps of Syncellus' Chronography (Greek text & Latin translation). | |||

As attested also by the completion of numerous dissertations in French and German universities, the [[Enoch Fragments of Syncellus]] quickly became the major focus of scholarly research on Enoch. They were included in works by [[Athanasius Kircher]] (''Oedipus Aegyptiacus'', 1652-54), [[Thomas Bangius]] (1657), [[Johann Heinrich Heidegger]] (1667-81), and [[Gottfried Vockerodt]] (''De societatibus et re literaria ante diluvium'', 1687), and discussed in works by [[Johannes Heinrich Ursinus]] (''De Zoroasre Bactiano, Hermetes Trismegisto, Sanchoniathone Phoenicio'', 1661) and [[Joachimus Joannes Maderus]] (''De Scriptis et Bibliothecis Antediluvianis'', 1666). The fragments also drew new attention on the citations contained in the [[Testaments of the Twelve Patriarchs]] (of which [[Johannes Ernestus Grabe]] published in 1698 the editio princeps of the Greek text). | |||

Rumors about the existence of a complete copy of the Book of Enoch in Ethiopic strengthened. In 1610 the Spanish Dominican [[Luis de Urreta]] claimed to have found the title in a list of works presented to [[Guglielmo Sirleto]], the Librarian of the Vatican, by Antonio Greco and Lorenzo Cremonese, who in the second half of the sixteenth century had been sent to Ethiopia by Pope Gregory XIII as part of a delegation. Urreta's position was popularized in the works of authors such as [[Samuel Purchas]] (Purchas His Pilgrimes, 1613), [[Nicolao Godinho]] (De Abassinorum rebus, 1615), [[George Sandys]] (A Relation of A Journey, 1615), and [[Peter Heylyn]] (Microcosmos, 1625). | Rumors about the existence of a complete copy of the Book of Enoch in Ethiopic strengthened. In 1610 the Spanish Dominican [[Luis de Urreta]] claimed to have found the title in a list of works presented to [[Guglielmo Sirleto]], the Librarian of the Vatican, by Antonio Greco and Lorenzo Cremonese, who in the second half of the sixteenth century had been sent to Ethiopia by Pope Gregory XIII as part of a delegation. Urreta's position was popularized in the works of authors such as [[Samuel Purchas]] (Purchas His Pilgrimes, 1613), [[Nicolao Godinho]] (De Abassinorum rebus, 1615), [[George Sandys]] (A Relation of A Journey, 1615), and [[Peter Heylyn]] (Microcosmos, 1625). | ||

Following these reports, the French intellectual and collector [[Nicolas-Claude Fabri de Peiresc]] (1580-1637) made strong efforts to recover the Ethiopic book of Enoch. He thought he had reached its goal when a ms arrived from Egypt in 1636 thanks to the mediation of Capuchin [[Gilles de Loches]] (Aegidius Lochiensis) and [[Agathange de Vendôme]]. The ms however remained unpublished and untranslated. The publication of [[Pierre Gassendi]]'s biography of Pereisc in 1641 (ET 1657 by [[William Rand]]) fostered for decades the illusion that a copy of the lost book of Enoch actually existed in Europe. The explicit reference to "Mazhapha Einok, or, the Prophecy of Enoch, which Ægidius Lochiensis, a learned Eastern Traveller, told Peireschius that he had found in an old Library at Alexandria containing eight thousand volumes" was included in 1675 in [[Thomas Browne]]'s catalogue of "remarkable books, antiquities, pictures and rarities of several kinds, scarce or never seen by any man now living" (Musaeum Clausum; or, Bibliotheca abscondita). Hopes to recover the lost book of Enoch suffered a major blow in 1681 when Ethiopist [[Hiob Ludolf]] finally had to chance to examine the ms purchased by Peiresc and demonstrated that it did not contain the prophecies of Enoch but was a copy of an ancient theological treatise with mere allusions to the book of Enoch. | Following these reports, the French intellectual and collector [[Nicolas-Claude Fabri de Peiresc]] (1580-1637) made strong efforts to recover the Ethiopic book of Enoch. He thought he had reached its goal when a ms arrived from Egypt in 1636 thanks to the mediation of Capuchin [[Gilles de Loches]] (Aegidius Lochiensis) and [[Agathange de Vendôme]]. The ms however remained unpublished and untranslated. The publication of [[Pierre Gassendi]]'s biography of Pereisc in 1641 (ET 1657 by [[William Rand]]) fostered for decades the illusion that a copy of the lost book of Enoch actually existed in Europe. The explicit reference to "Mazhapha Einok, or, the Prophecy of Enoch, which Ægidius Lochiensis, a learned Eastern Traveller, told Peireschius that he had found in an old Library at Alexandria containing eight thousand volumes" was included in 1675 in [[Thomas Browne]]'s catalogue of "remarkable books, antiquities, pictures and rarities of several kinds, scarce or never seen by any man now living" (Musaeum Clausum; or, Bibliotheca abscondita). Hopes to recover the lost book of Enoch suffered a major blow in 1681 when Ethiopist [[Hiob Ludolf]] finally had to chance to examine the ms purchased by Peiresc and demonstrated that it did not contain the prophecies of Enoch but was a copy of an ancient theological treatise with mere allusions to the book of Enoch--the treatise De mysteriis coeli & terrae, & de la S.S. Trinitate ("The Book of the Mysteries of Heaven and Earth") by Abba Bahaila Michaelem. | ||

In 1659 [[Méric Casaubon]] dismissed [[John Dee]]'s magic treatise as a work of sorcery, yet Enoch remained a popular figure in esoteric and literary circles, as the model (and the object) of mystical revelations. In 1665 an anonymous pamphlet was published in England, claiming to contain the revelation of the prophecies of Enoch. In 1667 [[John Milton]]'s visionary poem Paradise Lost gave a prominent role to Enoch and the myth of the Fallen Angels; Milton made extensive use of the [[Enoch Fragments of Syncellus]], but also of popular esoteric speculations on Enoch. In 1694 [[Jane Lead]] published a book detailing her mystical experiences of conversation with the angels under the title, "The Enochian Walks with God." | In 1659 [[Méric Casaubon]] dismissed [[John Dee]]'s magic treatise as a work of sorcery, yet Enoch remained a popular figure in esoteric and literary circles, as the model (and the object) of mystical revelations. In 1665 an anonymous pamphlet was published in England, claiming to contain the revelation of the prophecies of Enoch. In 1667 [[John Milton]]'s visionary poem Paradise Lost gave a prominent role to Enoch and the myth of the Fallen Angels; Milton made extensive use of the [[Enoch Fragments of Syncellus]], but also of popular esoteric speculations on Enoch. In 1682 the Capuchin Dionysius von Luxemburg in his ''Leben Antichristi'' reiterated the medieval belief in the coming of Enoch and Elijah at the end of times. In 1694 [[Jane Lead]] published a book detailing her mystical experiences of conversation with the angels under the title, "The Enochian Walks with God." | ||

For his antiquity the character of Enoch continued to be associated (or even identified) with other mythical figures of ancient wisdom. Kircher viewed him as the founder of Egyptian Wisdom and once again, identified him with Hermes Trismegistus. At the end of the 17th century, the Jesuit [[Joachim Bouvet]] (1656–1732), a leader of the Figurist movement of Jesuit missionaries in China, claimed that Enoch and Fu Xi, the supposed author of the I Ching (or Classic of Changes), as well as Zoroaster and Hermes Trismegistus, were really the same person. | For his antiquity the character of Enoch continued to be associated (or even identified) with other mythical figures of ancient wisdom. Kircher viewed him as the founder of Egyptian Wisdom and once again, identified him with Hermes Trismegistus. At the end of the 17th century, the Jesuit [[Joachim Bouvet]] (1656–1732), a leader of the Figurist movement of Jesuit missionaries in China, claimed that Enoch and Fu Xi, the supposed author of the I Ching (or Classic of Changes), as well as Zoroaster and Hermes Trismegistus, were really one and the same person. | ||

@2014 Gabriele Boccaccini, University of Michigan | @2014 Gabriele Boccaccini, University of Michigan | ||

| Line 32: | Line 89: | ||

File:Athanasius Kircher.jpg|Athanasius Kircher | File:Athanasius Kircher.jpg|Athanasius Kircher | ||

File:Thomas Browne.jpg|Thomas Browne | File:Thomas Browne.jpg|Thomas Browne | ||

</gallery> | </gallery> | ||

Latest revision as of 14:36, 19 December 2019

|

The page: Enochic Studies--1600s, includes (in chronological order) scholarly and literary works in the field of Enochic Studies, made in the 17th century, or between 1600 and 1699.  John Milton dictating "Paradise Lost" to his daughters

|

Enochic Studies : 2020s -- 2010s -- 2000s -- 1990s -- 1980s -- 1970s -- 1960s -- 1950s -- 1940s -- 1930s -- 1920s -- 1910s -- 1900s -- 1850s -- 1800s -- 1700s -- 1600s -- 1500s -- 1450s -- Home Timeline : 2020s -- 2010s -- 2000s -- 1990s -- 1980s -- 1970s -- 1960s -- 1950s -- 1940s -- 1930s -- 1920s -- 1910s -- 1900s -- 1850s -- 1800s -- 1700s -- 1600s -- 1500s -- 1450s -- Medieval -- Home

|

History of Research (1600s) -- Notes

At the beginning of the 17th century, scholars shifted their attention from esoteric sources to the Christian chronographical tradition, which until that moment had been largely neglected. In 1601 Italian-French-Dutch scholar Joseph Justus Scaliger located a 11th-century ms of the work of Syncellus in the former library of Catherine de Medici. The Enoch fragments contained in the text were collected by his friend Isaac Casaubon in 1602 at the National Library in Paris, and published by Scaliger in 1606. They were discussed by Johannes Drusius in 1612 and by Jacques Bolduc (De ecclesia ante legem) in 1626, and translated into English by Samuel Purchas in 1613. In 1652 Jacques Goar published the editio princeps of Syncellus' Chronography (Greek text & Latin translation).

As attested also by the completion of numerous dissertations in French and German universities, the Enoch Fragments of Syncellus quickly became the major focus of scholarly research on Enoch. They were included in works by Athanasius Kircher (Oedipus Aegyptiacus, 1652-54), Thomas Bangius (1657), Johann Heinrich Heidegger (1667-81), and Gottfried Vockerodt (De societatibus et re literaria ante diluvium, 1687), and discussed in works by Johannes Heinrich Ursinus (De Zoroasre Bactiano, Hermetes Trismegisto, Sanchoniathone Phoenicio, 1661) and Joachimus Joannes Maderus (De Scriptis et Bibliothecis Antediluvianis, 1666). The fragments also drew new attention on the citations contained in the Testaments of the Twelve Patriarchs (of which Johannes Ernestus Grabe published in 1698 the editio princeps of the Greek text).

Rumors about the existence of a complete copy of the Book of Enoch in Ethiopic strengthened. In 1610 the Spanish Dominican Luis de Urreta claimed to have found the title in a list of works presented to Guglielmo Sirleto, the Librarian of the Vatican, by Antonio Greco and Lorenzo Cremonese, who in the second half of the sixteenth century had been sent to Ethiopia by Pope Gregory XIII as part of a delegation. Urreta's position was popularized in the works of authors such as Samuel Purchas (Purchas His Pilgrimes, 1613), Nicolao Godinho (De Abassinorum rebus, 1615), George Sandys (A Relation of A Journey, 1615), and Peter Heylyn (Microcosmos, 1625).

Following these reports, the French intellectual and collector Nicolas-Claude Fabri de Peiresc (1580-1637) made strong efforts to recover the Ethiopic book of Enoch. He thought he had reached its goal when a ms arrived from Egypt in 1636 thanks to the mediation of Capuchin Gilles de Loches (Aegidius Lochiensis) and Agathange de Vendôme. The ms however remained unpublished and untranslated. The publication of Pierre Gassendi's biography of Pereisc in 1641 (ET 1657 by William Rand) fostered for decades the illusion that a copy of the lost book of Enoch actually existed in Europe. The explicit reference to "Mazhapha Einok, or, the Prophecy of Enoch, which Ægidius Lochiensis, a learned Eastern Traveller, told Peireschius that he had found in an old Library at Alexandria containing eight thousand volumes" was included in 1675 in Thomas Browne's catalogue of "remarkable books, antiquities, pictures and rarities of several kinds, scarce or never seen by any man now living" (Musaeum Clausum; or, Bibliotheca abscondita). Hopes to recover the lost book of Enoch suffered a major blow in 1681 when Ethiopist Hiob Ludolf finally had to chance to examine the ms purchased by Peiresc and demonstrated that it did not contain the prophecies of Enoch but was a copy of an ancient theological treatise with mere allusions to the book of Enoch--the treatise De mysteriis coeli & terrae, & de la S.S. Trinitate ("The Book of the Mysteries of Heaven and Earth") by Abba Bahaila Michaelem.

In 1659 Méric Casaubon dismissed John Dee's magic treatise as a work of sorcery, yet Enoch remained a popular figure in esoteric and literary circles, as the model (and the object) of mystical revelations. In 1665 an anonymous pamphlet was published in England, claiming to contain the revelation of the prophecies of Enoch. In 1667 John Milton's visionary poem Paradise Lost gave a prominent role to Enoch and the myth of the Fallen Angels; Milton made extensive use of the Enoch Fragments of Syncellus, but also of popular esoteric speculations on Enoch. In 1682 the Capuchin Dionysius von Luxemburg in his Leben Antichristi reiterated the medieval belief in the coming of Enoch and Elijah at the end of times. In 1694 Jane Lead published a book detailing her mystical experiences of conversation with the angels under the title, "The Enochian Walks with God."

For his antiquity the character of Enoch continued to be associated (or even identified) with other mythical figures of ancient wisdom. Kircher viewed him as the founder of Egyptian Wisdom and once again, identified him with Hermes Trismegistus. At the end of the 17th century, the Jesuit Joachim Bouvet (1656–1732), a leader of the Figurist movement of Jesuit missionaries in China, claimed that Enoch and Fu Xi, the supposed author of the I Ching (or Classic of Changes), as well as Zoroaster and Hermes Trismegistus, were really one and the same person.

@2014 Gabriele Boccaccini, University of Michigan

Pages in category "Enochic Studies--1600s"

The following 32 pages are in this category, out of 32 total.

1

- Thesaurus temporum (1606 Scaliger), book

- Historia ecclesiastica... de la Etiopia (1610 Urreta), book

- Henoch; sive, De patriarcha Henoch (1612 Drusius), book

- Purchas His Pilgrimage (1613 Purchas), book

- De Abassinorum rebus (1615 Godinho), book

- A Relation of a Journey Begun An. Dom. 1610 (1615 Sandys), book

- Microcosmus (1621 Heylyn), book

- De ecclesia ante legem (The Church before the Law / 1626 Bolduc), book

- Exegesis prophetiae Henochi, Iudae v. 14. 15 de Christi ad iudicium adventu glorioso (1627 Schaller / Dorsch), dissertation

- Viri illustris Nicolai Claudij Fabricij de Peiresc (Life of the Renowned Nicolaus Claudius Fabricius of Peiresk / 1641 Gassendi), book

- Typus adscensionis dominicae illustrissimus, hoc est, de Henochi immutatione et in Coelos translatione disputatio (1647 Müller / Henrici), dissertation

- Georgii Monachi Chronographia, et Nicephori Patriarchae Breviarivm Chronographicvm (1652 Goar), book

- Oedipus Aegyptiacus (1652-54 Kircher), book

- Caelum Orientis et prisei mundi (1657 Bangius), book

- The Mirrour of True Nobility & Gentility = Viri illustris Nicolai Claudij Fabricij de Peiresc (1657 @1641 Gassendi / Rand), book (English ed.)

- A True & Faithful Relation of What Passed for Many Years between Dr. John Dee and Some Spirits (1659 Casaubon), book

- De adventu Domini glorioso ad supremum iudicium meditatio: super dictum prophetico-apostolicum patriarchae Henochi ex epist. Judae com. XIV. XV. (1660 Leibnitz / Geier), dissertation

- Bibliotheca Historiae Sacrae Veteris Testamenti (1662-64 Schotanus), book

- The Revelation of God & His Glory (1665 R.B.), book

- Paradise Lost (1667 Milton), poetry

- De Historia Sacra Patriarcharum (1667-81 Heidegger), book

- Henoch (1670 Hülsemann / Pfeiffer), dissertation

- Historia Aethiopica (1681 Ludolf), book

- Leben Antichristi (1682 Dionysius von Luxemburg), vision

- Musaeum Clausum; or, Bibliotheca abscondita (Sealead Museum; or, The Hidden Library / 1684 Browne), book

- De societatibus et re literaria ante diluvium (1687 Vockerodt), book

- De libro Henochi prophetico (1694 Kleinpaul / Albinus), dissertation

- The Enochian Walks with God (1694 Lead), vision

- Spicilegium SS. patrum, ut et hæreticorum, seculi post Christum natum I. II. & III. (1698 Grabe), book