Martin Spett (M / Poland, 1928-2019), Holocaust survivor

Martin Spett (M / Poland, 1928-2019), Holocaust survivor

Rosa Spett (F / Poland, 1932), Holocaust survivor

- KEYWORDS : <Poland> <Tarnow Ghetto> <Bergen-Belsen> <Magdeburg Train>

- MEMOIRS : Reflections of the Soul (2002)

Biography

Martin (2 Dec 1929) and Rosa (29 Sep 1932) Spett were born in Tarnow, Poland. After surviving the Tarnow Ghetto, they were deported to Bergen-Belsen. They were liberated on Apr 13, 1945 on board of the Magdeburg Train near Farsleben. Martin wrote a book of memoirs.

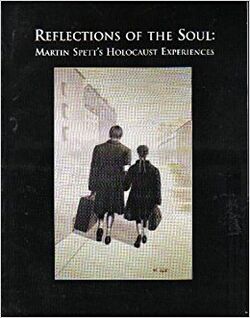

Book : Reflections of the Soul (2002)

- Martin Spett, Reflections of the Soul: Martin Spett's Holocaust Experiences, ed. Jeff Horn (Manhattan College Holocaust Resource Center, 2002)

USHMM ID Card

Known as Monek, Martin was the elder of two children raised by Jewish parents in the large town of Tarnow. His mother was an American citizen who had been raised in Poland. His father worked at the city's tax office. As a child, Martin liked to collect stamps and catch lizards. His parents wanted him to be a pharmacist, but he wanted to be an artist when he grew up.

1933-39: When the Germans occupied Tarnow in September 1939 after war began, Martin was 10 years old. The soldiers, in beautiful uniforms, were polite. But then they started forcing Jews to clean the streets of horse manure with their bare hands. Going to see his rabbi for a Sabbath lesson, Martin found Germans kicking him around in his prayer shawl. In Hebrew, he yelled to Martin, "Run!" Turning to escape, he heard a shot fired. Rabbi Wrubel was dead.

1940-44: In 1940 Martin and his family were forced out of their apartment. After the Germans began rounding up Jews for deportation, his father and uncle dug two ditches underneath the floorboards at his uncle's lumberyard. The day before the next deportation they hid beneath the floorboards. Lying on their backs in the dark for four days, they heard shouting, shooting and dogs barking. During the roundup they heard two Poles above them trying to catch Jews. One peed on them without knowing they were there. When it was finally quiet, they emerged.

Martin was deported to the Bergen-Belsen camp and was freed from an evacuation train by American troops on April 13, 1945. He immigrated to the United States in 1947.

USHMM Oral Interview

Martin Spett, born on December 2, 1928 in Tarnów, Poland, describes his childhood; the German occupation of Tarnów in 1939; his family losing their apartment in 1940; hiding in an attic when the first massacre of Jews occurred; having to finally register as a Jew in May 1943 and go to Bergen-Belsen, where he was allegedly to be part of an exchange for German prisoners of war; being liberated on April 13, 1945 by Allied troops during his transport to Theresienstadt; spending some time in Belgium after the war; and immigrating to the United States in 1947.

The Riverdale Press (3 november 2019)

Martin Spett, who shined the light of truth on the Holocaust, dies at 90.

Martin Spett promised his father he would never discuss the Holocaust. It’s a promise that led off Spett’s 2002 book “Reflections of the Soul,” and the same promise Rabbi Barry Dov Katz shared to begin his eulogy of Martin Spett, a locally renowned Holocaust survivor who died Oct. 20 at 90.

“His father told Martin that the stories of those years were too dark, too gruesome for people to believe,” Katz told the family and friends who gathered at Conservative Synagogue Adath Israel of Riverdale last week to remember Spett.

“He wanted his son to start a new life, one filled with light.”

Spett did exactly that. Once his family escaped the Polish ghetto and the horrors of the German concentration camp Bergen-Belsen, Spett found the light that evaded him his entire childhood. He got married, raised a family, became a leather craftsman, and did everything he could to put the atrocities of World War II behind him.

But in 1980, a university professor published a book claiming the Holocaust was a myth.

“Martin knew that he could not remain silent,” Katz said in his eulogy. “He needed to respond to the darkness of Holocaust denial with the light of truth about what happened to him and his family.”

The truth is not an easy one to witness, let alone live. Yet Spett did exactly that until Allied forces rescued him and hundreds of others from a train many of the Jews packed on board believed were taking them to their deaths. He wrote books, he sat for interviews, he would tell his story to anyone who would listen.

In fact, that’s how Martha Frazer met him. In the 1990s, the then social worker was teaching Hebrew school at CSAIR, and felt it was important these sixth- and seventh-graders had a chance to interact with a living witness to the Holocaust. Spett wasn’t the only survivor of that dark time attending the synagogue, but his approach to telling the story was quite unique.

Walking through the mind

“I took a group of children to Martin’s apartment to do an interview with him,” Frazer said. “But he used more than words. He had painted his memories of the Holocaust, and many of those paintings were there in his apartment. My son Ben, who was about 11 at the time, never forgot Martin because of those paintings.”

That interaction would create a lifelong commitment for Frazer telling first-hand stories about the Holocaust. She would ultimately work with director Steven Spielberg’s Shoah Visual History Foundation, which he founded soon after the release of his critically acclaimed film “Schindler’s List” that was tasked with interviewing 50,000 Holocaust survivors.

She also found herself working closely with Manhattan College, which around the same time established the school’s Holocaust, Genocide & Interfaith Education Center under history professor Frederick Schweitzer.

Mehnaz Afridi took over as the center’s director in 2011, and one of the first things she did was take the time to meet Martin Spett.

“He took me for coffee at the Riverdale Diner, and he just wanted to know who I was,” Afridi said. “We talked about his story, and he talked to me about his painting and how important it was for him, to use that medium to express what happened.

“I remember his intensity looking into my eyes, sharing his story blow-by-blow to me. I think we were there for three hours.”

Yet, Spett was a popular speaker about the Holocaust not just because of the story he had to tell, Afridi added, but the fact that he did it with such positivity.

“He would be smiling when he talked to you,” she said. “I would see my students’ faces light up. They were kind of living this moment with him.”

Finding the light

Spett would serve on the board up until a few years ago after his wife, Joan, passed and his own health started to falter, Afridi said. Yet, he would always be calling, asking how things were going, and what he could do.

In fact, many of Spett’s paintings are part of an exhibit on display at Manhattan College’s Holocaust Center, Afridi said.

Spett is survived by a son and daughter, Ari and Lana, as well as his grandchildren. He had learned how to craft leather in Brussels after the war, Rabbi Katz said, and would find his way to New York’s Garment District, becoming known for his work restoring fine leather goods from some of the biggest brand names on the market.

The living witnesses to the Holocaust is an exclusive club no one wanted to join, but it’s also shrinking as time passes. Martin Wolpoff, who was quite active in CSAIR’s men’s club with Spett, fears that the impact of the Holocaust will eventually become lost on future generations.

“I’m concerned that memories of the Holocaust is not going to continue without these voices,” he said. “I’m concerned additionally with the growth of anti-Semitism here in the city, and in the world in general.”

That’s why it’s important to keep stories like Spett’s alive, Afridi said. And it doesn’t hurt to have different ways of expressing those stories, like with Spett’s paintings.

“Seeing his paintings are like walking through somebody’s mind,” Afridi said. “They can’t describe it in words, but they can show it to you.”

Spett could use the pen just as much as he could the paintbrush. Katz shared Spett’s own words from his memoir on the legacy he hopes to instill.

“I believe that we must fight the arrogant and unbounded philosophy of hatred that emerged most virulently in Germany during this era,” Spett wrote. “We must respond to any form of racial verbal abuse or physical manifestations of bigotry.

“People who seek to dehumanize others who are different from them, or who wish to find scapegoats for their own failings and frailties, are everywhere. They must be opposed to prevent them from festering as they did in Germany.”

It was the light Spett had found that he hoped the rest of the world would discover.

“Martin lived his whole life trying to understand the darkness of people’s souls, even as he found ways to embrace life, to be joyful and to bring light into the world,” Katz said.

“I hope that Martin knows peace and blessing. I hope that he knows how remarkable it was for a boy whose formal schooling ended in sixth grade, who witnessed the darkest period of the modern era, to emerge as a formidable and trailblazing educator, an important member of this community, a loving husband, and father, and grandfather.

“I hope he knows light.”