Difference between revisions of "Gods & Demigods"

| Line 64: | Line 64: | ||

or the Messiah anointed and adopted as the [[Son of God]]: | or the Messiah anointed and adopted as the [[Son of God]]: | ||

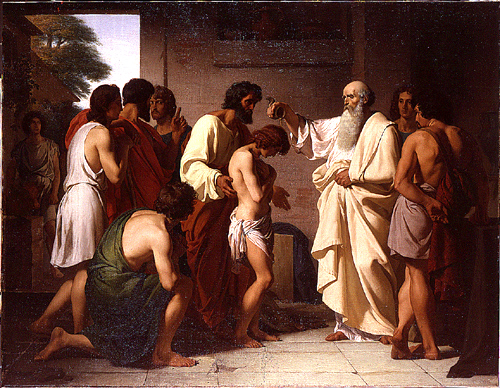

[[File:David Samuel Biennourry.jpg| | [[File:David Samuel Biennourry.jpg|600px]] | ||

[[Samuel Anoints David (1842 Biennourry), art]]]] | [[Samuel Anoints David (1842 Biennourry), art]]]] | ||

Revision as of 13:40, 2 February 2016

The existence of many Gods was assumed by most people in antiquity

Gods and Lords in the Greco-Roman World

In ancient polytheism "divinity" was not restricted to one God or a group of gods. People believed that there were different degrees of divinity.

In Greek-Roman Mythology there was a complex hierarchy of "divine beings." Everyone who had "super-human" powers was labeled "divine."

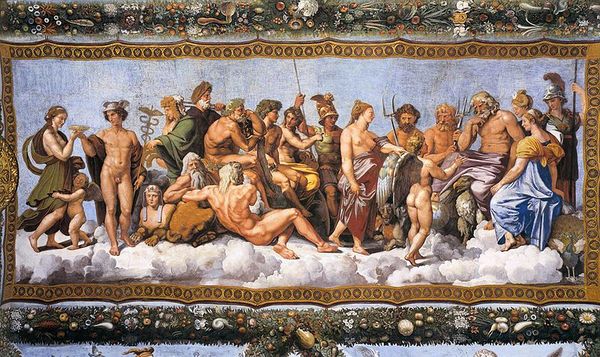

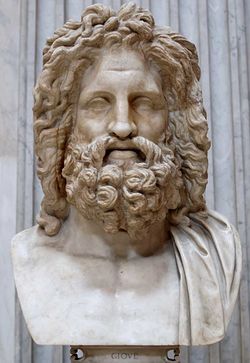

At the top there were the "gods" (THEOI), the highest twelve gods who were believed to live on Mount Olympus, lead by their king Zeus.

See also Twelve Olympians, namely, Zeus, Hera, Poseidon, Demeter, Athena, Apollo, Artemis, Ares, Aphrodite, Hephaestus, Hermes and either Hestia, or Dionysus.

Then there were many demigods (or "Lords" [KYRIOI]), the superheroes of antiquity.

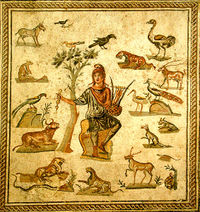

Usually, they were children of gods and humans, like Orpheus, Perseus or Aesculapius:

Or were "adopted" by a god as "sons of God" (Alexander the Great, Augustus, Nero)

In recent times the demigods have become popular iv TV series and videogames:

God and Lords in Judaism

For Jews (and early Christians) there is only one God (THEOS) in heaven: the Father and Maker of Everything. They also believed, however, in a complex hierarchy of "divine" beings.

Below God are other "divine" beings, i.e. the Angels (LORDS) :

and a few humans who have become angels, like Enoch and Elijah:

or the Messiah anointed and adopted as the Son of God:

Samuel Anoints David (1842 Biennourry), art]]

The "divine" Jesus

Where is the risen Jesus? As the Messiah, the Forgiver and the future Judge, he was understood as a "divine" being, but to which degree?

The first Christians, like Paul, never called Jesus "God" (or THEOS). They preferred to use the term "KYRIOS" (or "son of God").

" We know that no idol in the world really exists, and that "there is no God but one. 5 Indeed, even though there may be so-called gods in heaven or on earth--as in fact there are many gods and many lords-- 6 yet for us there is one God, the Father, from whom are all things and for whom we exist, and one Lord, Jesus Christ, through whom are all things and through whom we exist. (1 Corinthians 8:4-6).

At the end, the term "God" (THEOS) would be applied to Jesus for the first time only at the end of the first century in the Gospel of John. The discussion about the relationship between Jesus, God the Father and the other "divine" beings would remain at the center of the Christian theological debate for centuries.

Pagan and Christian iconography of the Gods

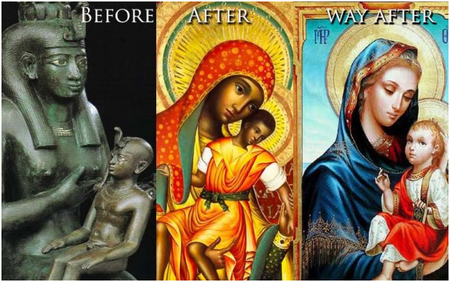

Ancient Jews (and Christians) strongly opposed any form of idol worship. Some Jews totally rejected the use of any kind of image. Many Jews, however, understood the power of images and thought that the best way to reject idolatry was not to suppress pagan representations but to use them for they own religious purposes.

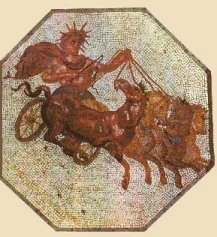

In ancient Jewish-Hellenistic synagogues, the pagan representation of the Zodiac with at center the chariot of Apollo was commonly used as a symbol of the unity and order of the universe:

Early Christians inherited from Hellenistic Jews the same attitude. They strongly rejected any form of idol worship; see already Paul. And yet they used pagan images to deliver their own message.

The ancient representations of pagan "demigods" (like Orpheus) or mediator "gods" (like Hermes) provided the first models to the early Christian iconography of Jesus.

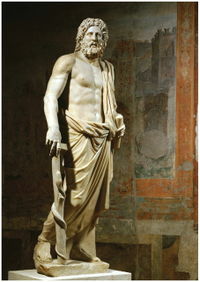

Zeus became God the Father:

The model for the representations of the [[Madonna and Child the was provided by the ancient iconography of the Egyptian goddess Isis:

Traditional images of gods (here Apollo carrying the baby Dionysus) were also used in the description of Saints:

See 1 Corinthians and then the Letter to the Hebrews