Difference between revisions of "Category:Qumran Studies--1950s"

| Line 18: | Line 18: | ||

In the meantime, in November 1951, Roland de Vaux and his team from the ASOR began a full excavation of [[Qumran]] and the surrounding area. The finding of identical jars in Cave 1 and at the site of [[Qumran]] suggested a close archaeological connection. In early 1952 a new cave (Cave 2) with new fragments was discovered by the Bedouin and on March 14 archaeologists first entered Cave 3. It became a race between the Bedouin and the archaeologists. In September-December 1952 Caves 4-5-6 were identified by the ASOR teams. Between 1953 and 1956, [[Roland de Vaux]] led four more archaeological expeditions in the area to uncover scrolls and artifacts. The last cave, Cave 11, was discovered in 1956 and yielded the last fragments to be found in the vicinity of Qumran. After 1956, no additional caves or scrolls were found in the area. | In the meantime, in November 1951, Roland de Vaux and his team from the ASOR began a full excavation of [[Qumran]] and the surrounding area. The finding of identical jars in Cave 1 and at the site of [[Qumran]] suggested a close archaeological connection. In early 1952 a new cave (Cave 2) with new fragments was discovered by the Bedouin and on March 14 archaeologists first entered Cave 3. It became a race between the Bedouin and the archaeologists. In September-December 1952 Caves 4-5-6 were identified by the ASOR teams. Between 1953 and 1956, [[Roland de Vaux]] led four more archaeological expeditions in the area to uncover scrolls and artifacts. The last cave, Cave 11, was discovered in 1956 and yielded the last fragments to be found in the vicinity of Qumran. After 1956, no additional caves or scrolls were found in the area. | ||

The majority of the newly-found fragments became property of the [[Palestine Archaeological Museum]] (now commonly known as the [[Rockefeller Museum]]) in East Jerusalem and were stored there since 1953. As the Museum became the center for the study of the manuscripts, Harding began to assembly an international team of specialists. Jozef Milik and Frank Cross were to first scholars to join the team in 1953. They were followed in 1954 by Patrick Skehan, John Strugnell, Dominique Barthelemy, Jean Starcky, Clause-Hunno Hunzinger, and John Marco Allegro. | |||

The | The team worked in very difficult conditions; with virtually no technological support, they could count only on their linguistic skill to solve the gigantic puzzle made of thousands of unidentified fragments. Under these circumstances it is amazing what they were able to accomplish. The scrolls however suffered deterioration and damage from their transportation and handling. The poor storage conditions at the "Scrollery" of the Museum and in the Ottoman Bank vault (where they were temporarily located from 1956 to the Spring of 1957 during the Suez Canal Crisis) made many of the fragments deteriorate to the point of becoming illegible. Fortunately, the Museum had all the material photographed by local Arab photographer [[Najib Albina]]. | ||

While the team of scholars and archaeologists worked in their secluded location in Palestine, the excitement for the discovery grew internationally far beyond the scholarly community. To the popularity of the scrolls and the creation of the "myth" of Qumran greatly contributed in 1955 the work of the American journalist [[Edmund Wilson]]. His book, translated into several languages, proved the appeal of the discovery also among non-specialists. | |||

In 1956 the decision was taken to open the [[Copper Scroll]] (found in 1952), by cutting it in small segments. The complex operation was carried out by Prof. James Baker at the University of Manchester. Shortly afterwards, the government of Jordan gave [[John Marco Allegro]] permission to search for the treasures described in the text, but with no results. | In 1956 the decision was taken to open the [[Copper Scroll]] (found in 1952), by cutting it in small segments. The complex operation was carried out by Prof. James Baker at the University of Manchester. Shortly afterwards, the government of Jordan gave [[John Marco Allegro]] permission to search for the treasures described in the text, but with no results. | ||

In 1957, Josef Milik offered | In 1957-58, Josef Milik and Frank Cross offered the first general assessments of ten years of research on the scrolls. The Essene connection was firmly established and the scholarly interest focused on the theological features of the Qumran community and the implications on Christian Origins. | ||

Revision as of 00:29, 2 July 2014

Qumran Studies in the 1950s--Works and Authors

< 1940s -- 1950s -- 1960s -- 1970s -- 1980s -- 1990s -- 2000s -- 2010s -- ... >

Overview

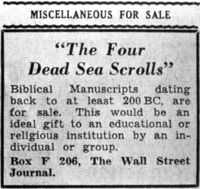

In 1950 Millar Burrows, with the assistance of John C. Trever and William H. Brownlee, published the complete Isaiah Scroll, the Habakkuk Commentary and the Community Rule from Cave 1, without revealing the exact origin and provenience of the manuscripts. The negotiations for the purchase of the manuscripts were still open and there were concerns about their unclear legal state. Eventually, the son of Eleazar Sukenik and Israeli archaeologist Yigael Yadin was able to purchase the four manuscripts from cave 1, advertised for sale by the Syrian Metropolitan Archbishop in a famous ad on the Wall Street Journal on June 1, 1954. The seven scrolls from Cave 1 were now reunited under the ownership of the new State of Israel.

In the meantime, in November 1951, Roland de Vaux and his team from the ASOR began a full excavation of Qumran and the surrounding area. The finding of identical jars in Cave 1 and at the site of Qumran suggested a close archaeological connection. In early 1952 a new cave (Cave 2) with new fragments was discovered by the Bedouin and on March 14 archaeologists first entered Cave 3. It became a race between the Bedouin and the archaeologists. In September-December 1952 Caves 4-5-6 were identified by the ASOR teams. Between 1953 and 1956, Roland de Vaux led four more archaeological expeditions in the area to uncover scrolls and artifacts. The last cave, Cave 11, was discovered in 1956 and yielded the last fragments to be found in the vicinity of Qumran. After 1956, no additional caves or scrolls were found in the area.

The majority of the newly-found fragments became property of the Palestine Archaeological Museum (now commonly known as the Rockefeller Museum) in East Jerusalem and were stored there since 1953. As the Museum became the center for the study of the manuscripts, Harding began to assembly an international team of specialists. Jozef Milik and Frank Cross were to first scholars to join the team in 1953. They were followed in 1954 by Patrick Skehan, John Strugnell, Dominique Barthelemy, Jean Starcky, Clause-Hunno Hunzinger, and John Marco Allegro.

The team worked in very difficult conditions; with virtually no technological support, they could count only on their linguistic skill to solve the gigantic puzzle made of thousands of unidentified fragments. Under these circumstances it is amazing what they were able to accomplish. The scrolls however suffered deterioration and damage from their transportation and handling. The poor storage conditions at the "Scrollery" of the Museum and in the Ottoman Bank vault (where they were temporarily located from 1956 to the Spring of 1957 during the Suez Canal Crisis) made many of the fragments deteriorate to the point of becoming illegible. Fortunately, the Museum had all the material photographed by local Arab photographer Najib Albina.

While the team of scholars and archaeologists worked in their secluded location in Palestine, the excitement for the discovery grew internationally far beyond the scholarly community. To the popularity of the scrolls and the creation of the "myth" of Qumran greatly contributed in 1955 the work of the American journalist Edmund Wilson. His book, translated into several languages, proved the appeal of the discovery also among non-specialists.

In 1956 the decision was taken to open the Copper Scroll (found in 1952), by cutting it in small segments. The complex operation was carried out by Prof. James Baker at the University of Manchester. Shortly afterwards, the government of Jordan gave John Marco Allegro permission to search for the treasures described in the text, but with no results.

In 1957-58, Josef Milik and Frank Cross offered the first general assessments of ten years of research on the scrolls. The Essene connection was firmly established and the scholarly interest focused on the theological features of the Qumran community and the implications on Christian Origins.

Pages in category "Qumran Studies--1950s"

The following 111 pages are in this category, out of 111 total.

1

- Observations sur le commentaire d'Habacuc découvert près de la Mer Morte (1950 Dupont-Sommer), book

- Hymns from the Judean Scrolls (1950 Wallenstein), book

- The Dead Sea Manual of Discipline (1951 Brownlee), book

- Deux manuscrits hébreux de la mer Morte (Two Hebrew Manuscripts from the Dead Sea / 1951 Del Medico), book

- The Hebrew Scrolls, from the Neighborhood of Jericho and the Dead Sea (1951 Driver), book

- Die hebräischen Handschriften aus der Höhle (The Hebrew Manuscripts from the Cave / 1951 Kahle), book

- Dead Sea Scrolls Fragment of the Book of Enoch (1951 Milik), essay

- La communauté de la nouvelle alliance (The Community of the New Covenant / 1951 Vermès), book

- Die Handschriftenfunde am Toten Meer (The Manuscript Discoveries at the Dead Sea / 1952-58 Bardtke), book

- The Qumrân (Dead Sea) Scrolls and Palaeography (1952 Birnbaum), book

- (+) The Dead Sea Scrolls: A Preliminary Survey = Aperçus préliminaire sur les manuscrits de la mer Morte (1952 @1950 Dupont-Sommer / Rowley), book (English ed.)

- De handschriften van de Dode Zee (Dead Sea Scrolls / 1952 Edelkoort), book

- Handskrifterna från Qumran I-III = The Dead Sea Scrolls I-III (1952 Reicke), book

- The Zadokite Fragments and the Dead Sea Scrolls (1952 Rowley), book

- The Zadokite Fragments (1952 Zeitlin), book

- Sacrifice and Worship among the Jewish Sectarians of the Dead Sea (Qumran) Scrolls (1953 Baumgarten), book

- Serekh ha-yahad / Regula unionis seu manuale disciplinae (1953 Boccaccio, Berardi), book

- Nouveau aperçus sur les manuscrits de la mer Morte (The Jewish Sect of Qumran and the Essenes / 1953 Dupont-Sommer), book

- Studien zum Habakuk-Kommentar vom Toten Meer (Studies on Pesher Habakkuk from the Dead Sea / 1953 Elliger), book

- Les manuscrits du désert de Juda (The Manuscripts of the Desert of Judah / 1953 Vermès), book

- The Jewish Sect of Qumran and the Essenes = Nouveau aperçus sur les manuscrits de la mer Morte (1954 Dupont-Sommer / Barnett), book (English ed.)

- Le maître de justice d'après les documents de la mer Morte (The Teacher of Righteousness according to the Dead Sea Scrolls / 1954 Michel), book

- Die Söhne des Lichtes (The Sons of Light / 1954 Molin), book

- The Zadokite Documents (1954 Rabin), book

- (++) Qumran Cave I (DJD 1 / 1955 Barthélemy, Milik), book

- Interpretatio Habacuc (1955 Boccaccio, Berardi), book

- Discoveries in the Judaean Desert (1955-2011 Clarendon), book series

- I manoscritti ebraici del deserto di Giuda (1955 Moscati), book

- Der Schatz von Jericho (The Treasure of Jericho / 1955 Schlisske), book

- Les manuscrits hebreux du désert de Juda (The Hebrew Manuscripts of the Desert of Judah / 1955 Vincent), book

- The Dead Sea Scrolls (1956 Allegro), book

- Second Thoughts on the Dead Sea Scrolls (1956 Bruce), book

- The Teacher of Righteousness in the Qumran Texts (1956 Bruce), book

- Die Schriftrollen vom Toten Meer = Dead Sea Scrolls (1956 Burrows / Cornelius), book (German ed.)

- (+) The Meaning of the Dead Sea Scrolls (1956 Davies), non-fiction

- Einleitung in das Alte Testament unter Einschluss der Apokryphen und Pseudepigraphen, 2nd ed. (1956 Eissfeldt), book

- (+) The Qumran Community: Its History and Scrolls (1956 Fritsch), book

- Los descubrimientos de Qumrán (The Qumran Discoveries / 1956 González Lamadrid), book

- Dødehavsrullene (Dead Sea Scrolls / 1956 Kapelrud), book

- The Dead Sea Scrolls and the Bible (1956 Murphy), book

- Håndskriftfundene i Juda ørken: Dødehavsteksterne (The Manuscript Findings in the Desert of Judah: The Dead Sea Scrolls / 1956 Nielsen), book

- Zur theologischen Terminologie der Qumran-Texte (The Theological Terminology of Qumran Texts / 1956 Nötscher), book

- Handskrifterna från Qumran IV-V = The Dead Sea Scrolls IV-V (1956 Ringgren), book

- (+) Discovery in the Judean Desert (1956 Vermès), book

- Die Handschriftenfunde beim Toten Meer und ihre Bedeutung für die Erforschung der Heiligen Schrift (The Manuscript Discoveries at the Dead Sea and Their Importance for the Study of the Holy Scriptures / 1956 Wildberger), book

- De boekrollen van de Dode Zee = The Scrolls from the Dead Sea (1956 @1955 Wilson / Herschberg), non-fiction (Dutch ed.)

- Die Schriftrollen vom Toten Meer = The Scrolls from the Dead Sea (1956 @1955 Wilson / Ewers), non-fiction (German ed.)

- Los rollos del Mar Muerto = The Scrolls from the Dead Sea (1956 @1955 Wilson / Speratti Piñero), non-fiction (Spanish ed.)

- Skriftrullerne fra Det døde Hav = The Scrolls from the Dead Sea (1956 Wilson), non-fiction (Danish ed.)

- The Dead Sea Scrolls and Modern Scholarship (1956 Zeitlin), book

- Die Botschaft vom Toten Meer = The Dead Sea Scrolls (1957 Allegro / Hilsbecher), book (German ed.)

- Los manuscritos del Mar Muerto = The Dead Sea Scrolls (1957 Allegro / Fuentes Benot), book (Spanish ed.)

- 死海の書 = The Dead Sea Scrolls (1957 Allegro / Kitazawa), book (Japanese ed.)

- Spätjüdisch-häretischer und frühchristlicher Radikalismus: Jesus von Nazareth und die essenische Qumransekte (1957 Braun), book

- Bibliographie zu den Handschriften vom Toten Meer (Bibliography of the Dead Sea Scrolls / 1957 Burchard), book

- Les manuscrits de la Mer Morte = Dead Sea Scrolls (1956 Burrows / Glotz, Franck), book (French ed.)

- Prima di Cristo: la scoperta dei rotoli del Mar Morto (1957 Burrows / Dell'Oro), book (Italian ed.)

- Skriftfynden vid Döda Havet = Dead Sea Scrolls (1957 Burrows / Ringgren), book (Swedish ed.)

- Le Docteur de Justice et Jésus-Christ (Christ and the Teacher of Righteousness / 1957 Carmignac), book

- Dieci anni di scoperte nel deserto di Giuda = Dix ans de découvertes dans le Désert de Juda (1957 @1957 / Milik / Rinaldi), book (Italian ed.)

- (+) Vondsten in de woestijn van Juda (The Excavations at Qumran / 1957 Ploeg), book

- Qumran Studies (1957 Rabin), book

- Jesus und die Wüstengemeinde am Toten Meer (Jesus and the Wilderness Community at Qumran / 1957 Stauffer), book

- Les manuscrits de la Mer Morte (The Dead Sea Scrolls / 1957 Strasbourg), edited volume

- The Manual of Discipline (1957 Wernberg-Møller), book

- Die Messianischen Vorstellungen der Gemeinde von Qumrân (The Messianic Ideas of the Qumran Community / 1957 Woude), book

- (+) The Message of the Scrolls (1957 Yadin), book

- Los rollos del Mar Muerto = The Message of the Scrolls (1959 @1957 Yadin / Trabb), book (Spanish ed.)

- I rotoli del Mar Morto = The Dead Sea Scrolls (1958 Allegro), book (Italian ed.)

- Os manuscritos do Mar Morto = The Dead Sea Scrolls (1958 Allegro / Costa), book (Portuguese ed.)

- The People of the Dead Sea Scrolls (1958 Allegro), book

- Los rollos del Mar Muerto = Dead Sea Scrolls (1958 Burrows / Speratti Piñero), book (Spanish ed.)

- (+) The Dead Sea Scrolls and Primitive Christianity = Les manuscrits de la Mer Morte et les origines du christianisme / 1958 @1957 Daniélou), book (English ed.)

- Qumran und der Ursprung des Christentums = Les manuscrits de la Mer Morte et les origines du christianisme (The Dead Sea Scrolls and Primitive Christianity / 1958 Daniélou / Schilling), book (German ed.)

- Bibliography of the Dead Sea Scrolls, 1948-1957 (1958 LaSor), book

- Valor escriturario de los hallazgos en el mar Muerto (Scriptural Value of the Findings at the Dead Sea / 1958 Millàs i Vallicrosa), book

- (+) The Excavations at Qumran = Vondsten in de woestijn van Juda (1958 @1957 Ploeg / Smyth), book (English ed.)

- Revue de Qumrân (1958-), journal

- La Bibbia e le scoperte moderne (1958 Ricciotti), book

- The Historical Background of the Dead Sea Scrolls (1958 Roth), book

- Die Gemeinde vom Toten Meer (The Dead Sea Community / 1958 Schubert), book

- Manuskrypty z Qumran a chrzescijanstwo (Manuscripts from Qumran and Christianity / 1958 Strakowski), book

- The Copper Scrolls (1958 Weinreb), novel

- Dödahavsrullarna = The Dead Sea Scrolls (1959 Allegro / Davidson), book (Swedish ed.)

- Regula Congregationis (1959 Boccaccio, Berardi), book

- The Novice of Qumran (1959 Brogan), novel

- The Text of Habakkuk in the Ancient Commentary from Qumran (1959 Brownlee), book

- Nya upptäckter om Dödahavsrullarna = More Light on the Dead Sea Scrolls (1959 Burrows / Ringgren), book (Swedish ed.)

- Los manuscritos del Mar Muerto y los orígenes del cristianismo (1959 Daniélou / Ferrari, Mejía) = Les manuscrits de la Mer Morte et les origines du christianisme (The Dead Sea Scrolls and Primitive Christianity / 1957 Daniélou), book (Argentine ed.)

- L'enigma dei manoscritti del Mar Morto = L'énigme des manuscrits de la Mer Morte (1959 @1957 Del Medico / Cantini), book (Italian ed.)

- Les écrits esséniens découverts près de la mer Morte (The Essene Writings from Qumran / 1959 Dupont-Sommer), book

- Hebräer, Essener, Christen (1959 Kosmala), book

- הלשון והרקע הלשוני של מגילת ישעיהו השלמה ממגילות ים המלח (The Language and Linguistic Background of the Isaiah Scroll / 1959 Kutscher), book

- Кумранские рукописи и их историческое значение (The Dead Sea Scrolls and Their Historical Significance / 1959 Livshits), book

- (+) Ten Years of Discoveries in the Wilderness of Judaea = Dix ans de découvertes dans le Désert de Juda / 1959 Milik / Strugnell), book (English ed.)

- Dødehavsteksterne (Dead Sea Scrolls / 1959 Nielsen, Otzen), book

- Inni di ringraziamento (Thanksgiving Hymns / 1959 Piattelli), book

- Funde in der Wüste Juda = Vondsten in de woestijn van Juda (The Excavations at Qumran / 1959 @1957 Ploeg / Schom), book (German ed.)

- Le rouleau de la guerre (The War Scroll / 1959 Ploeg), book

- The Dead Sea Community = Die Gemeinde vom Toten Meer (1959 Schubert / Doberstein), book (English ed.)

- Les esséniens (The Essenes / 1959 Sérouya), book

~

- Millar Burrows (1889-1980), American scholar

- André Dupont-Sommer (1900-1983), French scholar

- Jean Daniélou (1905-1974), scholar

- Jean-Dominique Barthélemy (1921-2002), scholar

- Józef T. Milik (1922-2006), Polish-French scholar

- Sabatino Moscati (M / Italy, 1923-1997), scholar

- Kurt Schubert (1923-2007), scholar

- Joseph M. Baumgarten (1928-2008), scholar

Media in category "Qumran Studies--1950s"

The following 17 files are in this category, out of 17 total.

- 1950 * Burrows.jpg 371 × 499; 24 KB

- 1950 * Dupont-Sommer.jpg 300 × 392; 44 KB

- 1955 * Burrows.jpg 677 × 1,000; 94 KB

- 1955 * Wilson.jpg 396 × 500; 44 KB

- 1956 * Gaster.jpg 336 × 499; 33 KB

- 1956 Graystone.jpg 692 × 1,000; 97 KB

- 1956 LaSor.jpg 707 × 1,000; 74 KB

- 1957 Allegro.jpg 700 × 1,000; 56 KB

- 1957 Danielou.jpg 686 × 1,000; 88 KB

- 1957 Howlett.jpg 1,018 × 1,500; 279 KB

- 1957 * Milik.jpg 347 × 499; 23 KB

- 1957-E * Stendahl.jpg 704 × 1,000; 64 KB

- 1958 * Burrows.jpg 337 × 499; 28 KB

- 1958 * Cross.jpg 300 × 458; 34 KB

- 1958 Robinson.jpg 300 × 300; 16 KB

- 1958-T Wilson it.jpg 800 × 1,139; 115 KB

- 1959-E Ploeg.jpg 1,384 × 2,000; 316 KB