Difference between revisions of "Category:Samaritan Schism (event)"

| (2 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 4: | Line 4: | ||

The '''Samaritan Schism''' refers to the religious separation between the [[Samaritans]] and the [[Judeans]] at the very end of the 5th century BCE. | The '''Samaritan Schism''' refers to the religious separation between the [[Samaritans]] and the [[Judeans]] at the very end of the 5th century BCE during the [[Persian Period]] under the rule of the [[Sanballats]]. | ||

* This page is edited by [[Gabriele Boccaccini]], University of Michigan | * This page is edited by [[Gabriele Boccaccini]], University of Michigan | ||

| Line 13: | Line 13: | ||

The roots of the conflict between Judah and Samaria go back to the monarchic period. At stake was the hegemony in the region--a situation that repeated after the Babylonian exile. In spite of their common religious roots, the Samaritans found themselves in the front line against any attempt at restoring an autonomous political or religious power in Judah, which would have diminished the hegemony they had gained in the region. Eventually, they could not stop the exiles' plan of reconstruction of the Jerusalem Temple, nor effectively challenge the Zadokite refusal to share the control of the rebuilt sanctuary with any local priesthood. The support the returnees received from the Persian administration under [[Darius I]] was a decisive factor in the setback. The political and economical power in the region, however, remained largely in the hands of the Samaritans. | The roots of the conflict between Judah and Samaria go back to the monarchic period. At stake was the hegemony in the region--a situation that repeated after the Babylonian exile. In spite of their common religious roots, the Samaritans found themselves in the front line against any attempt at restoring an autonomous political or religious power in Judah, which would have diminished the hegemony they had gained in the region. Eventually, they could not stop the exiles' plan of reconstruction of the Jerusalem Temple, nor effectively challenge the Zadokite refusal to share the control of the rebuilt sanctuary with any local priesthood. The support the returnees received from the Persian administration under [[Darius I]] was a decisive factor in the setback. The political and economical power in the region, however, remained largely in the hands of the Samaritans. | ||

The change in religious policy by [[Darius I]]' son, [[Xerses I]], revealed how precarious the situation of the returned exiles was. With a poor economy and without the military protection of walls Jerusalem was defenseless, and the Temple heavily depended on the support of outsiders. As governors of Samaria, the Sanballats regained some yards in Jerusalem with a covert and judicious policy of patronage. Had their influence not been strong in Jerusalem, they would never have succeeded in infiltrating even the Zadokite family structure of power through intermarriage. The lamentations of Malachi reflect the growing concerns of the Zadokite party over the objective weakness of the Temple administration (1:6--2:9) and the priesthood's tendency to compromise and establish economical and familiar links with "foreign people" (2:10-12). Without a decisive change in the balance of power in the region, the outcome would probably have been some political and religious accommodation between the Sanballats and the Zadokites. | The change in religious policy by [[Darius I]]' son, [[Xerses I]], revealed how precarious the situation of the returned exiles was. With a poor economy and without the military protection of walls Jerusalem was defenseless, and the Temple heavily depended on the support of outsiders. As governors of Samaria, the [[Sanballats]] regained some yards in Jerusalem with a covert and judicious policy of patronage. Had their influence not been strong in Jerusalem, they would never have succeeded in infiltrating even the Zadokite family structure of power through intermarriage. The lamentations of Malachi reflect the growing concerns of the Zadokite party over the objective weakness of the Temple administration (1:6--2:9) and the priesthood's tendency to compromise and establish economical and familiar links with "foreign people" (2:10-12). Without a decisive change in the balance of power in the region, the outcome would probably have been some political and religious accommodation between the Sanballats and the Zadokites. | ||

The Babylonian diaspora ran to the rescue, and thanks to personal connections with the Persian court and the new king, [[Artaxerses I]], [[Nehemiah]] was able to reverse the situation. It is pretty obvious that Sanballat was upset at seeing Jerusalem gaining political, economical and military autonomy, and frustrated at his failure to sabotage Nehemiah's plan. The walls of Jerusalem were a barrier against any hope of compromise with the Jerusalem priesthood. Now, it was just a matter of time before the political struggle turned into a religious schism. | The Babylonian diaspora ran to the rescue, and thanks to personal connections with the Persian court and the new king, [[Artaxerses I]], [[Nehemiah]] was able to reverse the situation. It is pretty obvious that Sanballat was upset at seeing Jerusalem gaining political, economical and military autonomy, and frustrated at his failure to sabotage Nehemiah's plan. The walls of Jerusalem were a barrier against any hope of compromise with the Jerusalem priesthood. Now, it was just a matter of time before the political struggle turned into a religious schism. | ||

| Line 19: | Line 19: | ||

At the end of the second mission of Nehemiah, the Zadokite party was strong enough to sever any residual tie with the Sanballats. The incident involved a distinguished member of the Zadokite family. "One of sons of [[Jehoiada]], son of the high priest [[Eliahib]], was the son-in-law of Sanballat the Horonite; and I chased him away" (Neh 13:28; cf. Josephus, Ant 11:302-312). | At the end of the second mission of Nehemiah, the Zadokite party was strong enough to sever any residual tie with the Sanballats. The incident involved a distinguished member of the Zadokite family. "One of sons of [[Jehoiada]], son of the high priest [[Eliahib]], was the son-in-law of Sanballat the Horonite; and I chased him away" (Neh 13:28; cf. Josephus, Ant 11:302-312). | ||

Josephus adds to the story many interesting details, including the names of Manasseh (ben Joiada) and Nicaso (bat Sanballat) as the banned couple. However, the chronological and genealogical framework he provides differs significantly, the episode being dated almost one century later. This does not imply an improbable repetition of events. Josephus also knew from his source that the incident occurred "under Darius" (Ant 11:311) and involved a Sanballat. He ignored, however, that the Sanballats were an ancient dynasty, with several individuals bearing the same name, not a single individual. The only Sanballat Josephus knew was the "one who was sent by Darius, the last king (of Persia), into Samaria" (Ant 11:302). It was therefore obvious for Josephus to believe that the Darius mentioned in his source was [[Darius III]], not the successor of [[Artaxerses I]], [[Darius II]]. He adjusted the historical and genealogical framework of the episode accordingly. | Josephus adds to the story many interesting details, including the names of Manasseh (ben Joiada) and Nicaso (bat Sanballat) as the banned couple. However, the chronological and genealogical framework he provides differs significantly, the episode being dated almost one century later. This does not imply an improbable repetition of events. Josephus also knew from his source that the incident occurred "under Darius" (Ant 11:311) and involved a [[Sanballat]]. He ignored, however, that the [[Sanballats]] were an ancient dynasty, with several individuals bearing the same name, not a single individual. The only [[Sanballat]] Josephus knew was the "one who was sent by Darius, the last king (of Persia), into Samaria" (Ant 11:302). It was therefore obvious for Josephus to believe that the Darius mentioned in his source was [[Darius III]], not the successor of [[Artaxerses I]], [[Darius II]]. He adjusted the historical and genealogical framework of the episode accordingly. | ||

As the marriage between members of influential families was a public and calculated political act, so was the request of divorce. The Zadokite leadership signaled to the world their freedom from the patronage of the Sanballats. As a good politician, Sanballat made the best of his defeat. According to Josephus, he promised his son-in-law "not only to preserve to him the honor of the priesthood but to procure for him the power and dignity of a high priest... and that he would build him a temple like that at Jerusalem upon Mount Gerizim" (Ant 11:310). Since the Deutenonomist legislation required only one sanctuary but did not specified its location, a member of the dominant priestly family (the [[House of Zadok]]) was just the one who was needed to give equal legitimacy to a religious schism and to a rival temple, and to create embarrassment to their adversaries by means of the similarities between the two traditions. Significantly, the source of Josephus speaks only of Sanballat's "promise" of a temple and provides no description of its actual construction; archaeological evidence shows it probably happened only "about the end of the fourth century BCE". | As the marriage between members of influential families was a public and calculated political act, so was the request of divorce. The Zadokite leadership signaled to the world their freedom from the patronage of the Sanballats. As a good politician, Sanballat made the best of his defeat. According to Josephus, he promised his son-in-law "not only to preserve to him the honor of the priesthood but to procure for him the power and dignity of a high priest... and that he would build him a temple like that at Jerusalem upon Mount Gerizim" (Ant 11:310). Since the Deutenonomist legislation required only one sanctuary but did not specified its location, a member of the dominant priestly family (the [[House of Zadok]]) was just the one who was needed to give equal legitimacy to a religious schism and to a rival temple, and to create embarrassment to their adversaries by means of the similarities between the two traditions. Significantly, the source of Josephus speaks only of Sanballat's "promise" of a temple and provides no description of its actual construction; archaeological evidence shows it probably happened only "about the end of the fourth century BCE". | ||

Latest revision as of 08:29, 20 January 2016

The Samaritan Schism refers to the religious separation between the Samaritans and the Judeans at the very end of the 5th century BCE during the Persian Period under the rule of the Sanballats.

- This page is edited by Gabriele Boccaccini, University of Michigan

Overview

The roots of the conflict between Judah and Samaria go back to the monarchic period. At stake was the hegemony in the region--a situation that repeated after the Babylonian exile. In spite of their common religious roots, the Samaritans found themselves in the front line against any attempt at restoring an autonomous political or religious power in Judah, which would have diminished the hegemony they had gained in the region. Eventually, they could not stop the exiles' plan of reconstruction of the Jerusalem Temple, nor effectively challenge the Zadokite refusal to share the control of the rebuilt sanctuary with any local priesthood. The support the returnees received from the Persian administration under Darius I was a decisive factor in the setback. The political and economical power in the region, however, remained largely in the hands of the Samaritans.

The change in religious policy by Darius I' son, Xerses I, revealed how precarious the situation of the returned exiles was. With a poor economy and without the military protection of walls Jerusalem was defenseless, and the Temple heavily depended on the support of outsiders. As governors of Samaria, the Sanballats regained some yards in Jerusalem with a covert and judicious policy of patronage. Had their influence not been strong in Jerusalem, they would never have succeeded in infiltrating even the Zadokite family structure of power through intermarriage. The lamentations of Malachi reflect the growing concerns of the Zadokite party over the objective weakness of the Temple administration (1:6--2:9) and the priesthood's tendency to compromise and establish economical and familiar links with "foreign people" (2:10-12). Without a decisive change in the balance of power in the region, the outcome would probably have been some political and religious accommodation between the Sanballats and the Zadokites.

The Babylonian diaspora ran to the rescue, and thanks to personal connections with the Persian court and the new king, Artaxerses I, Nehemiah was able to reverse the situation. It is pretty obvious that Sanballat was upset at seeing Jerusalem gaining political, economical and military autonomy, and frustrated at his failure to sabotage Nehemiah's plan. The walls of Jerusalem were a barrier against any hope of compromise with the Jerusalem priesthood. Now, it was just a matter of time before the political struggle turned into a religious schism.

At the end of the second mission of Nehemiah, the Zadokite party was strong enough to sever any residual tie with the Sanballats. The incident involved a distinguished member of the Zadokite family. "One of sons of Jehoiada, son of the high priest Eliahib, was the son-in-law of Sanballat the Horonite; and I chased him away" (Neh 13:28; cf. Josephus, Ant 11:302-312).

Josephus adds to the story many interesting details, including the names of Manasseh (ben Joiada) and Nicaso (bat Sanballat) as the banned couple. However, the chronological and genealogical framework he provides differs significantly, the episode being dated almost one century later. This does not imply an improbable repetition of events. Josephus also knew from his source that the incident occurred "under Darius" (Ant 11:311) and involved a Sanballat. He ignored, however, that the Sanballats were an ancient dynasty, with several individuals bearing the same name, not a single individual. The only Sanballat Josephus knew was the "one who was sent by Darius, the last king (of Persia), into Samaria" (Ant 11:302). It was therefore obvious for Josephus to believe that the Darius mentioned in his source was Darius III, not the successor of Artaxerses I, Darius II. He adjusted the historical and genealogical framework of the episode accordingly.

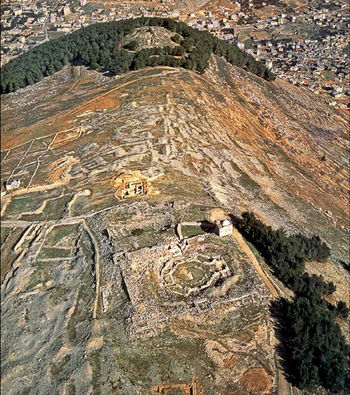

As the marriage between members of influential families was a public and calculated political act, so was the request of divorce. The Zadokite leadership signaled to the world their freedom from the patronage of the Sanballats. As a good politician, Sanballat made the best of his defeat. According to Josephus, he promised his son-in-law "not only to preserve to him the honor of the priesthood but to procure for him the power and dignity of a high priest... and that he would build him a temple like that at Jerusalem upon Mount Gerizim" (Ant 11:310). Since the Deutenonomist legislation required only one sanctuary but did not specified its location, a member of the dominant priestly family (the House of Zadok) was just the one who was needed to give equal legitimacy to a religious schism and to a rival temple, and to create embarrassment to their adversaries by means of the similarities between the two traditions. Significantly, the source of Josephus speaks only of Sanballat's "promise" of a temple and provides no description of its actual construction; archaeological evidence shows it probably happened only "about the end of the fourth century BCE".

Although the boundaries of separation between the two communities remained somehow uncertain for a long time, the wound in the Israelite body would never be healed. The destruction of the Samaritan Temple on Mount Gerizim by John Hyrcanus in 128 BCE only ratified the impossibility of reconciliation. The Samaritan Schism would never be recomposed, and members of the House of Zadok would continue to serve as High Priest in Samaria, from father to son, for centuries to come, ironically much longer than their relatives in Jerusalem. While the last Zadokite High Priest served in the Jerusalem Temple at the beginning of the 2nd century BCE, according to Samaritan tradition the Samaritan branch of the House of Zadok lasted until 1624 when the High Priest Shelemiah ben Pinhas died without male succession and the Samaritan High Priesthood was taken by Aaronite descendants. Today, the Samaritans still survive as a separate branch of Israelite religion.

The Samaritan Schism, in ancient sources

Book of Nehemiah

Neh 13:28 (NRSV) -- And one of the sons of Jehoiada, son of the high priest Eliashib, was the son-in-law of Sanballat the Horonite; I chased him away from me.

Josephus, Antiquities

Ant XI 7,2 -- 2. Now when John had departed this life, his son Jaddua succeeded in the high priesthood. He had a brother, whose name was Manasseh. Now there was one Sanballat, who was sent by Darius, the last king [of Persia], into Samaria. He was a Cutheam by birth; of which stock were the Samaritans also. This man knew that the city Jerusalem was a famous city, and that their kings had given a great deal of trouble to the Assyrians, and the people of Celesyria; so that he willingly gave his daughter, whose name was Nicaso, in marriage to Manasseh, as thinking this alliance by marriage would be a pledge and security that the nation of the Jews should continue their good-will to him.

Ant XI 8,2 -- 2. But the elders of Jerusalem being very uneasy that the brother of Jaddua the high priest, though married to a foreigner, should be a partner with him in the high priesthood, quarreled with him; for they esteemed this man’s marriage a step to such as should be desirous of transgressing about the marriage of [strange] wives, and that this would be the beginning of a mutual society with foreigners, although the offense of some about marriages, and their having married wives that were not of their own country, had been an occasion of their former captivity, and of the miseries they then underwent; so they commanded Manasseh to divorce his wife, or not to approach the altar, the high priest himself joining with the people in their indignation against his brother, and driving him away from the altar. Whereupon Manasseh came to his father-in-law, Sanballat, and told him, that although he loved his daughter Nicaso, yet was he not willing to be deprived of his sacerdotal dignity on her account, which was the principal dignity in their nation, and always continued in the same family. And then Sanballat promised him not only to preserve to him the honor of his priesthood, but to procure for him the power and dignity of a high priest, and would make him governor of all the places he himself now ruled, if he would keep his daughter for his wife. He also told him further, that he would build him a temple like that at Jerusalem, upon Mount Gerizzini, which is the highest of all the mountains that are in Samaria; and he promised that he would do this with the approbation of Darius the king. Manasseh was elevated with these promises, and staid with Sanballat, upon a supposal that he should gain a high priesthood, as bestowed on him by Darius, for it happened that Sanballat was then in years. But there was now a great disturbance among the people of Jerusalem, because many of those priests and Levites were entangled in such matches; for they all revolted to Manasseh, and Sanballat afforded them money, and divided among them land for tillage, and habitations also, and all this in order every way to gratify his son-in-law.

The Samaritan Schism in scholarship

External links

Pages in category "Samaritan Schism (event)"

The following 4 pages are in this category, out of 4 total.