Difference between revisions of "Gods & Demigods"

| (44 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

The existence of many Gods was assumed by most people in antiquity | The existence of many Gods was assumed by most people in antiquity | ||

==Gods and | ==Gods and Lords in the Greco-Roman World== | ||

What we now mean by “divine” was not what ancient people meant. We think that only God is "divine", while everybody else is not, but this is not what ancient people believed. | |||

In ancient polytheism "divinity" was not restricted to one God or a group of gods. It was first of all a matter of power. People believed that there were different degrees of divinity, from exalted humans to the supreme gods. | |||

In Greek-Roman Mythology there was a complex hierarchy of "divine beings." Everyone who had "super-human" powers was labeled "divine." | |||

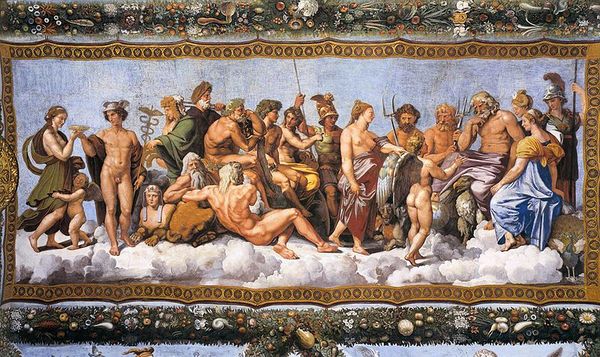

At the top of these truncated pyramid of divinity, there were the "gods" (THEOI), the highest twelve gods who were believed to live on Mount Olympus, lead by their king ''Zeus''. | |||

[[File:Council Gods Raphael.jpg|600px]] | [[File:Council Gods Raphael.jpg|600px]] | ||

See also [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Twelve_Olympians Twelve Olympians] | |||

See also [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Twelve_Olympians Twelve Olympians], namely, [[Zeus]], [[Hera]], [[Poseidon]], [[Demeter]], [[Athena]], [[Apollo]], [[Artemis]], [[Ares]], [[Aphrodite]], [[Hephaestus]], [[Hermes]] and either [[Hestia]], or [[Dionysus]]. | |||

Then there were many demigods (or "Lords" [KYRIOI]), the superheroes of antiquity. | |||

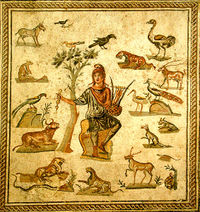

Usually, they were children of gods and humans, like [[Orpheus]], [[Perseus]] or [[Aesculapius]]: | |||

[[File:Orpheus.jpg|200px]] -- [[File:Perseus.jpg|200px]] -- [[File:Aesculapius.jpg|200px]] | |||

[[ | Or were "adopted" by a god as "sons of God" ([[Alexander the Great]], [[Augustus]], [[Nero]]) | ||

[[File:Alexander Great.jpg|200px]] - [[File:Emperor Augustus.jpg|200px]] - [[File:Emperor Nero.jpg|200px]] | |||

| Line 18: | Line 38: | ||

[[File:Xena.jpg|200px]] [[File:Hercules Disney.jpg|200px]] [[File: | [[File:Xena.jpg|200px]] [[File:Hercules Disney.jpg|200px]] [[File:Achilles Troy.jpg|200px]] | ||

[[File:Demigods Modern.jpg|600px]] | [[File:Demigods Modern.jpg|600px]] | ||

== | ==God and Lords in Judaism== | ||

Surprisingly, Jews did not differ substantially from their polytheistic neighbors in their understanding of the “divine.” Also for Jews the universe was populated by superhuman “divine” beings (angels), exalted humans and other manifestations of God. “Jews also believed that divinities could become human and humans could become divine.” The biggest difference was that the Jews conceived the truncated pyramid of polytheism as a perfect pyramid that had only one God at the top, their God, but still preserved the presence of numerous, “less divine” beings. | |||

For Jews (and early Christians) there is only one God (THEOS) in heaven. What make "God" unique is the fact that God in uncreated, and is the Father and Maker of Everything. Ancient Jews (and Christians) also believed, however, in a complex hierarchy of "divine" beings. | |||

[[File:God Father Cima.jpg|600px]] | [[File:God Father Cima.jpg|600px]] | ||

| Line 34: | Line 53: | ||

Below God are Angels | Below God are other "divine" beings, i.e. the Angels (LORDS). These less-divine, more-than-human beings could be still called “gods” by texts from the Second Temple period. They were "divine" but were created by the supreme God. | ||

[[File:Angel Peace.jpg|300px]] [[File:Angel Michael Reni.jpg|250px]] | [[File:Angel Peace.jpg|300px]] [[File:Angel Michael Reni.jpg|250px]] | ||

| Line 40: | Line 59: | ||

and a few humans who have become angels, like [[Enoch]] and [[Elijah]]: | |||

[[File:Enoch Hoet.jpg|250px]] [[File:Elijah Ascent.jpg|290px]] | |||

or the Messiah anointed and adopted as the [[Son of God]]: | |||

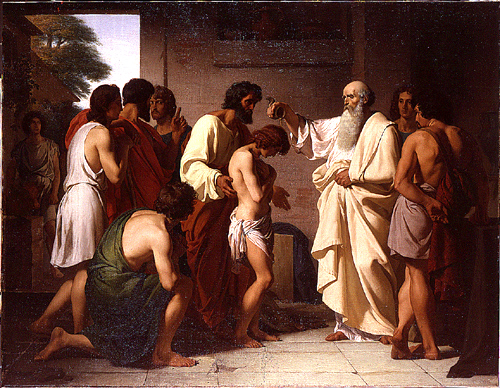

[[File:David Samuel Biennourry.jpg|550px]] | |||

[[Samuel Anoints David (1842 Biennourry), art]]]] | |||

==The "divine" Jesus== | |||

Where is the risen Jesus? As the Messiah, the Forgiver and the future Judge, he was understood as a "divine" being, but to which degree? | |||

[[File:Resurrection PieroFrancesca.jpg|400px]] | |||

Since a very early stage Christians attributed to Jesus some degree of "divinity" and venerated him as a divine agent. This does not mean however that Jesus was immediately given the same rank as [[God the Father]]. | |||

====Earliest traditions on Jesus the Prophet and the Messiah==== | |||

Many of Jesus’ sayings betray a clear prophetic self-consciousness by the teacher from Nazareth. Some of these sayings are recognized as perhaps the most authentic expression of the ipsissima verba of Jesus, such as when he expressed his disappointment to his hometown ("Prophets are not without honor, except in their hometown, and among their own kin, and in their own house,” Mc 6.4), or his prescient lament over Jerusalem ("Jerusalem, Jerusalem, the city that kills the prophets and stones those who are sent to you!,” Mt 23:37, Lk 13:34). | |||

There is no doubt, however, that the tendency of the Christian tradition (perhaps as early as the time of Jesus) was to give the teacher and prophet of Nazareth a very special relationship with God the Father and from the very beginning, superhuman features and functions. There never was something like a "Low Christology" in the early Jesus movement. In the very moment Jesus was claimed to be the messiah he was given a high "divine" status. | |||

The opinion of those who see in Jesus "one of the prophets," or the redivivus John Baptist or Elijah, is contrasted by the profession of faith of Peter: "You are the Messiah" (Mark 8:28-29). In essence, for the early Christians, Jesus was not simply a righteous prophet, but the Righteous One and as the eschatological Messiah, he was not just a son of God but the beloved Son of God. In the narratives of Jesus’ baptism and transfiguration, a voice from heaven proclaims, "This is my beloved Son in whom I am well pleased" (Mk 1:11 and 9:7). | |||

The association between the Messiah and "the son of God" was not a new Christian concept. It is a traditional idea that comes from the rituals of enthronement of the ancient King-Messiahs of the House of David (cf. 2 Samuel 7:14, 1 Cr 17:13; Ps 2:7; 110:3 [LXX]), to which the narratives of Jesus’ baptism and transfiguration are directly inspired. Paul also would use the same language of "adoption" in reference to Christ, who was "was descended from David according to the flesh" (Rom 1:3) and was "designated Son of God in power according to the spirit of holiness by his resurrection from the dead" (Rom 1:4). | |||

The theology of the Messiah [[Son of Davide]], however, does not seem to have been the central frame of reference for the understanding of Jesus the Messiah. The only case in which Jesus mentions the Messiah “son of David" is to deny the concept entirely. To the "[Pharisaic] scribes [who] say that the Messiah is the son of David", Jesus polemically replies that it cannot be because "David himself calls him 'Lord': How then can he be his son?" (Mark 12:35-37). The earliest Christian tradition assigned to Jesus only and exclusively sayings that related him to the “Son of Man,” the Danielic/Enochian pre-existing heavenly figure, whose name is “hidden” from the moment of creation to the time of the end, when he reveals himself as the Judge, and “comes in the glory of the Father with his angels" (Mark 8.38). With the coming of the Son of Man, the power of the 'strong man' of this world is put to end, for "someone stronger than he" has come (Luke 11:22), one that has the power to "tie him up" and "plunder his house" (Mark 3:27). It is to this figure of eschatological Judge that according to the Christian tradition [[John the Baptist]] also referred to in his preaching. | |||

The earliest Christian tradition, therefore, read and interpreted the experience of Jesus the Messiah by borrowing its categories from the [[Book of Daniel]] and the [[Book of Parables]]. It added two new elements. First, God's mercy required that before revealing himself as the eschatological Judge, the Son of Man had to come as the Forgiver. Second, this [[Son of Man]], manifested as the Forgiver and destined to to be the final judge has a name and an identity; he is [[Jesus of Nazareth]] who was given "authority on earth to forgive sins" (Mk 2:1-12, cf. Mt 9:1-8, Luke 5:17-26) and will come back as the Judge with the angels of heaven (Mk 14:61-62). | |||

====Paul's christology==== | |||

Paul opens his letters with a binitarian address to [[God the Father]] [theos]] and Jesus Christ the Son [kyrios]. | |||

Paul was very careful never to attribute to the “kyrios” Jesus the title of “theos” (God), which was unique to the Father. | |||

:"We know that no idol in the world really exists, and that "there is no God but one. Indeed, even though there are so-called gods in heaven or on earth—as in fact there are many theoi and kyrioi—yet for us there is only one theos, the Father, from whom are all things and for whom we exist, and one kyrios, Jesus Christ, through whom are all things and through whom we exist "(1 Cor 8:5-6). | |||

Only the Father is the Creator, while the Lord is the instrument of creation. | |||

The absence of the term Son of Man in Paul does not have to be interpreted as a rejection of the concept of the [[Son of Man]]. On the contrary, the christology of Paul does not radically depart from the Enochic pattern. There are indeed "Two Powers in Heaven" with clearly distinctive roles. Like the Enochic “Son of Man,” the Pauline Son-kyrios belongs to the heavenly sphere, and is separated from and subordinate to the Father-theos. | |||

On earth Jesus completed his mission of forgiveness through his self-sacrifice and death. He was the "paschal lamb" (1Cor 5:6), who died for our sins. | |||

At the end of time Jesus will return as the Judge in the Last Judgment; "for the Lord himself, with a cry of command, with the archangel's call and with the sound of God's trumpet, will descend from heaven" (1 Thess 4:16). | |||

Jesus however is "subjected" to the Father; he "belongs" to God. "As you belong to Christ, so Christ belongs to God" (1Cor 3:23). "Christ is the head of every man, and the husband is the head of his wife, and God is the head of Christ" (1Cor 11:3). At the end, after completing his final mission, "the Son, too, will be subjected to the One who put all things in subjection under him, so that God may be all in all" (1Cor 15:28). | |||

If Paul does not use the term “Son of Man” (even in contexts such as 1 Thess 4:16-17, where the reference to Daniel 7 would have made it obvious), it is because the title would have interfered with the parallelism he establishes between Adam and the new Adam, by suggesting the subordination of Jesus ben Adam to the first Adam. As the obedient son, Christ is compared to the disobedient son, Adam, with whom he shares the nature and dignity as the other “son of God.” Both were created in the image and likeness of God, taking upon himself the "form" of God; Adam and Jesus, however, are separated by a different fate, that is, one of guilt and transgression in the case of Adam, and the other of obedience and glory in the case of the new Adam. The kenosis of Adam is punishment caused by his disobedience, while in Jesus the kenosis is a voluntary choice for accomplishing his mission of forgiveness and is followed by his elevation and glorification (Phil 2:5-11). The veneration of Jesus, often mistaken as evidence of Jesus’ divine status, is the veneration due to the Son of Man at the time once his name is manifested. | |||

At the end, the term "God" (THEOS) would be applied to Jesus for the first time only at the end of the first century in the [[Gospel of John]]. The discussion about the relationship between Jesus, God the Father and the other "divine" beings would remain at the center of the Christian theological debate for centuries. | |||

==Pagan and Christian iconography of the Gods== | |||

Ancient Jews (and Christians) strongly opposed any form of [[idolatry|idol worship]]. Some Jews totally rejected the use of any kind of image. Many Jews, however, understood the power of images and thought that the best way to reject idolatry was not to suppress pagan representations but to use them for they own religious purposes. | |||

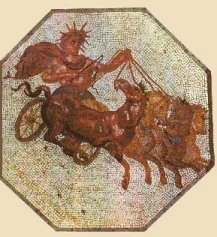

In ancient Jewish-Hellenistic synagogues, the pagan representation of the [[Zodiac]] with at center the chariot of [[Apollo]] was commonly used as a symbol of the unity and order of the universe: | |||

[[File:Hellenistic-Jewish Studies.jpg|700px]] | |||

Early Christians inherited from Hellenistic Jews the same attitude. They strongly rejected any form of [[idolatry|idol worship]]; see already [[Paul]]. And yet they used pagan images to deliver their own message. | |||

The ancient representations of pagan "demigods" (like [[Orpheus]]) or mediator "gods" (like [[Hermes]]) provided the first models to the early Christian iconography of [[Jesus]]. | |||

[[File:Orpheus.jpg|200px|A pagan representation of Orpheus]] | |||

[[File:Jesus Orpheus Ravenna.jpg|300px|Christ as Orpheus (Ravenna, Italy: Mausoleum of Gallia Placida, 5th cent.)]] | |||

[[File:Jesus Orpheus Rome.jpg|350px|Christ as Orpheus (Rome: Catacombs of Peter and Marcellus, 4th cent.)]] | |||

[[File:Jesus Hermes.jpg|400px]] | |||

[[File:Apollo Chariot.jpg|300px]] [[File:Jesus Apollo.jpg|300px]] | |||

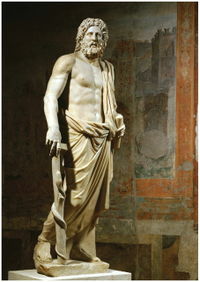

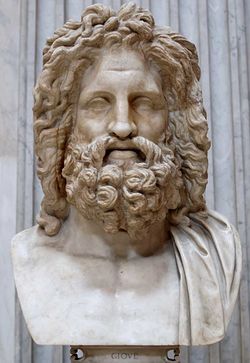

[[Zeus]] became [[God the Father]]: | |||

[[File:Zeus bust.jpg|250px]] [[File:God Masolino.jpg|400px]] | |||

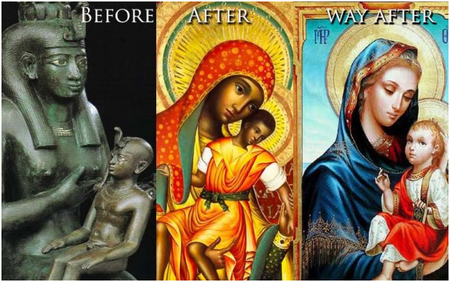

The model for the representations of the [[Madonna and Child the was provided by the ancient iconography of the Egyptian goddess Isis: | |||

[[File:Isis Mary.png|450px]] | |||

Traditional images of gods (here [[Apollo]] carrying the baby [[Dionysus]]) were also used in the description of Saints: | |||

[[File: | [[File:Hermes Dionysius.jpg|180px|Hermes and Infant Dionysius]] | ||

[[File:Jesus Dionysius.jpg|210px|St. Christofer and Infant Jesus]] | |||

See [[1 Corinthians]] and then the [[Letter to the Hebrews]] | |||

Latest revision as of 09:02, 29 January 2018

The existence of many Gods was assumed by most people in antiquity

Gods and Lords in the Greco-Roman World

What we now mean by “divine” was not what ancient people meant. We think that only God is "divine", while everybody else is not, but this is not what ancient people believed.

In ancient polytheism "divinity" was not restricted to one God or a group of gods. It was first of all a matter of power. People believed that there were different degrees of divinity, from exalted humans to the supreme gods.

In Greek-Roman Mythology there was a complex hierarchy of "divine beings." Everyone who had "super-human" powers was labeled "divine."

At the top of these truncated pyramid of divinity, there were the "gods" (THEOI), the highest twelve gods who were believed to live on Mount Olympus, lead by their king Zeus.

See also Twelve Olympians, namely, Zeus, Hera, Poseidon, Demeter, Athena, Apollo, Artemis, Ares, Aphrodite, Hephaestus, Hermes and either Hestia, or Dionysus.

Then there were many demigods (or "Lords" [KYRIOI]), the superheroes of antiquity.

Usually, they were children of gods and humans, like Orpheus, Perseus or Aesculapius:

Or were "adopted" by a god as "sons of God" (Alexander the Great, Augustus, Nero)

In recent times the demigods have become popular iv TV series and videogames:

God and Lords in Judaism

Surprisingly, Jews did not differ substantially from their polytheistic neighbors in their understanding of the “divine.” Also for Jews the universe was populated by superhuman “divine” beings (angels), exalted humans and other manifestations of God. “Jews also believed that divinities could become human and humans could become divine.” The biggest difference was that the Jews conceived the truncated pyramid of polytheism as a perfect pyramid that had only one God at the top, their God, but still preserved the presence of numerous, “less divine” beings.

For Jews (and early Christians) there is only one God (THEOS) in heaven. What make "God" unique is the fact that God in uncreated, and is the Father and Maker of Everything. Ancient Jews (and Christians) also believed, however, in a complex hierarchy of "divine" beings.

Below God are other "divine" beings, i.e. the Angels (LORDS). These less-divine, more-than-human beings could be still called “gods” by texts from the Second Temple period. They were "divine" but were created by the supreme God.

and a few humans who have become angels, like Enoch and Elijah:

or the Messiah anointed and adopted as the Son of God:

Samuel Anoints David (1842 Biennourry), art]]

The "divine" Jesus

Where is the risen Jesus? As the Messiah, the Forgiver and the future Judge, he was understood as a "divine" being, but to which degree?

Since a very early stage Christians attributed to Jesus some degree of "divinity" and venerated him as a divine agent. This does not mean however that Jesus was immediately given the same rank as God the Father.

Earliest traditions on Jesus the Prophet and the Messiah

Many of Jesus’ sayings betray a clear prophetic self-consciousness by the teacher from Nazareth. Some of these sayings are recognized as perhaps the most authentic expression of the ipsissima verba of Jesus, such as when he expressed his disappointment to his hometown ("Prophets are not without honor, except in their hometown, and among their own kin, and in their own house,” Mc 6.4), or his prescient lament over Jerusalem ("Jerusalem, Jerusalem, the city that kills the prophets and stones those who are sent to you!,” Mt 23:37, Lk 13:34).

There is no doubt, however, that the tendency of the Christian tradition (perhaps as early as the time of Jesus) was to give the teacher and prophet of Nazareth a very special relationship with God the Father and from the very beginning, superhuman features and functions. There never was something like a "Low Christology" in the early Jesus movement. In the very moment Jesus was claimed to be the messiah he was given a high "divine" status.

The opinion of those who see in Jesus "one of the prophets," or the redivivus John Baptist or Elijah, is contrasted by the profession of faith of Peter: "You are the Messiah" (Mark 8:28-29). In essence, for the early Christians, Jesus was not simply a righteous prophet, but the Righteous One and as the eschatological Messiah, he was not just a son of God but the beloved Son of God. In the narratives of Jesus’ baptism and transfiguration, a voice from heaven proclaims, "This is my beloved Son in whom I am well pleased" (Mk 1:11 and 9:7).

The association between the Messiah and "the son of God" was not a new Christian concept. It is a traditional idea that comes from the rituals of enthronement of the ancient King-Messiahs of the House of David (cf. 2 Samuel 7:14, 1 Cr 17:13; Ps 2:7; 110:3 [LXX]), to which the narratives of Jesus’ baptism and transfiguration are directly inspired. Paul also would use the same language of "adoption" in reference to Christ, who was "was descended from David according to the flesh" (Rom 1:3) and was "designated Son of God in power according to the spirit of holiness by his resurrection from the dead" (Rom 1:4).

The theology of the Messiah Son of Davide, however, does not seem to have been the central frame of reference for the understanding of Jesus the Messiah. The only case in which Jesus mentions the Messiah “son of David" is to deny the concept entirely. To the "[Pharisaic] scribes [who] say that the Messiah is the son of David", Jesus polemically replies that it cannot be because "David himself calls him 'Lord': How then can he be his son?" (Mark 12:35-37). The earliest Christian tradition assigned to Jesus only and exclusively sayings that related him to the “Son of Man,” the Danielic/Enochian pre-existing heavenly figure, whose name is “hidden” from the moment of creation to the time of the end, when he reveals himself as the Judge, and “comes in the glory of the Father with his angels" (Mark 8.38). With the coming of the Son of Man, the power of the 'strong man' of this world is put to end, for "someone stronger than he" has come (Luke 11:22), one that has the power to "tie him up" and "plunder his house" (Mark 3:27). It is to this figure of eschatological Judge that according to the Christian tradition John the Baptist also referred to in his preaching.

The earliest Christian tradition, therefore, read and interpreted the experience of Jesus the Messiah by borrowing its categories from the Book of Daniel and the Book of Parables. It added two new elements. First, God's mercy required that before revealing himself as the eschatological Judge, the Son of Man had to come as the Forgiver. Second, this Son of Man, manifested as the Forgiver and destined to to be the final judge has a name and an identity; he is Jesus of Nazareth who was given "authority on earth to forgive sins" (Mk 2:1-12, cf. Mt 9:1-8, Luke 5:17-26) and will come back as the Judge with the angels of heaven (Mk 14:61-62).

Paul's christology

Paul opens his letters with a binitarian address to God the Father [theos]] and Jesus Christ the Son [kyrios].

Paul was very careful never to attribute to the “kyrios” Jesus the title of “theos” (God), which was unique to the Father.

- "We know that no idol in the world really exists, and that "there is no God but one. Indeed, even though there are so-called gods in heaven or on earth—as in fact there are many theoi and kyrioi—yet for us there is only one theos, the Father, from whom are all things and for whom we exist, and one kyrios, Jesus Christ, through whom are all things and through whom we exist "(1 Cor 8:5-6).

Only the Father is the Creator, while the Lord is the instrument of creation.

The absence of the term Son of Man in Paul does not have to be interpreted as a rejection of the concept of the Son of Man. On the contrary, the christology of Paul does not radically depart from the Enochic pattern. There are indeed "Two Powers in Heaven" with clearly distinctive roles. Like the Enochic “Son of Man,” the Pauline Son-kyrios belongs to the heavenly sphere, and is separated from and subordinate to the Father-theos.

On earth Jesus completed his mission of forgiveness through his self-sacrifice and death. He was the "paschal lamb" (1Cor 5:6), who died for our sins.

At the end of time Jesus will return as the Judge in the Last Judgment; "for the Lord himself, with a cry of command, with the archangel's call and with the sound of God's trumpet, will descend from heaven" (1 Thess 4:16).

Jesus however is "subjected" to the Father; he "belongs" to God. "As you belong to Christ, so Christ belongs to God" (1Cor 3:23). "Christ is the head of every man, and the husband is the head of his wife, and God is the head of Christ" (1Cor 11:3). At the end, after completing his final mission, "the Son, too, will be subjected to the One who put all things in subjection under him, so that God may be all in all" (1Cor 15:28).

If Paul does not use the term “Son of Man” (even in contexts such as 1 Thess 4:16-17, where the reference to Daniel 7 would have made it obvious), it is because the title would have interfered with the parallelism he establishes between Adam and the new Adam, by suggesting the subordination of Jesus ben Adam to the first Adam. As the obedient son, Christ is compared to the disobedient son, Adam, with whom he shares the nature and dignity as the other “son of God.” Both were created in the image and likeness of God, taking upon himself the "form" of God; Adam and Jesus, however, are separated by a different fate, that is, one of guilt and transgression in the case of Adam, and the other of obedience and glory in the case of the new Adam. The kenosis of Adam is punishment caused by his disobedience, while in Jesus the kenosis is a voluntary choice for accomplishing his mission of forgiveness and is followed by his elevation and glorification (Phil 2:5-11). The veneration of Jesus, often mistaken as evidence of Jesus’ divine status, is the veneration due to the Son of Man at the time once his name is manifested.

At the end, the term "God" (THEOS) would be applied to Jesus for the first time only at the end of the first century in the Gospel of John. The discussion about the relationship between Jesus, God the Father and the other "divine" beings would remain at the center of the Christian theological debate for centuries.

Pagan and Christian iconography of the Gods

Ancient Jews (and Christians) strongly opposed any form of idol worship. Some Jews totally rejected the use of any kind of image. Many Jews, however, understood the power of images and thought that the best way to reject idolatry was not to suppress pagan representations but to use them for they own religious purposes.

In ancient Jewish-Hellenistic synagogues, the pagan representation of the Zodiac with at center the chariot of Apollo was commonly used as a symbol of the unity and order of the universe:

Early Christians inherited from Hellenistic Jews the same attitude. They strongly rejected any form of idol worship; see already Paul. And yet they used pagan images to deliver their own message.

The ancient representations of pagan "demigods" (like Orpheus) or mediator "gods" (like Hermes) provided the first models to the early Christian iconography of Jesus.

Zeus became God the Father:

The model for the representations of the [[Madonna and Child the was provided by the ancient iconography of the Egyptian goddess Isis:

Traditional images of gods (here Apollo carrying the baby Dionysus) were also used in the description of Saints:

See 1 Corinthians and then the Letter to the Hebrews