Tova Friedman (F / Poland, 1938), Holocaust survivor

Tova Friedman / Tola Grossman (F / Poland, 1938), Holocaust survivor

- KEYWORDS : <Poland> <Tomaszów Mazowiecki Ghetto> <KZ Starachowice> <Auschwitz> <Liberation of Auschwitz>

- MEMOIRS : Kinderlager (1998), by Milton J. Nieuwsma

Biography

Tova Friedman was born September 7, 1938 in Gdynia, Poland, a suburb of Danzig. Her family came from Tomaszow Mazowiecki, Poland and returned there as soon as the war broke out.

Under Nazi occupation, the family was forced to live in the Tomaszów Mazowiecki Ghetto. The 15 thousand Jews were cramped into six 4-story buildings unable to leave without special permission. "We lived with our grandparents and other people in tight quarters with the children sleeping and eating under the table." Starvation, shootings and deportation soon decreased the population. Those that managed to survive were shipped off to Nazi labor camps. A handful were kept as the cleanup squad. "I held my mother’s hand as she and my father picked up the corpses and brought them to the communal grave."

The next destination was Starachowice where parents worked at an ammunition factory. "When the children’s selections came, I watched from my hiding place as all remaining children disappeared."

Eventually the family was sent to Auschwitz. They survived. "At 5-1/2 years old my head was shaven and I was tattooed. I survived hunger, disease and a trip to the gas chamber. My mother’s ingenuity saved me when instead of going on the death march we both hid ourselves with corpses and lived to experience the liberation of Auschwitz, by the Russians on January 27, 1945."

After the war, Tova and her mother reunited with her father (he also miraculously survived at Dachau). They emigrated to the United States in 1950. Tova grew up in Brooklyn. She received her Bachelors of Arts degree in psychology from Brooklyn College, a Master of Arts in Black literature from City College of New York and her Master of Arts in social work from Rutgers University. She taught at the Hebrew University in Jerusalem and was Director of Jewish Family Service of Somerset and Warren Counties for over 20 years, working there as a therapist.

Auschwitz picture

Tova appears in a famous photo shot after the liberation of the camp on January 27, 1945. The photo pictures: (1) Tova Friedman; (2) Sarah Ludwig; and (3) Michael Bornstein.

For a joke of fate, all the three children pictured in the photo lived in New Jersey, without knowing of each other. They finally reunited on June 4, 2017.

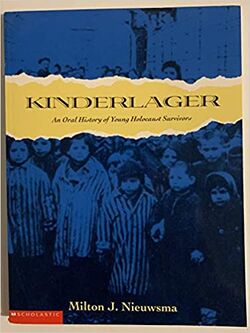

Book : Kinderlager (1998), by Milton J.Nieuwsma

A retelling of the experience of Tova Friedman, Frieda Tenenbaum, and Rachel Hyams, thrre of the youngest survivors from Auschwitz.

"As time begins to silence the first-person voices of older survivors, this account of the experiences of three young girls, one of them possibly the youngest survivor of the death camp of Auschwitz-Birkenau, comes as a powerful witness to the Holocaust. Tova Friedman, Frieda Tenenbaum, and Rachel Hyams all came from the same small town in Poland. After a series of ghettos and forced labor camps, all three girls were transported to Auschwitz with their mothers and for a time were together in the Kinderlager barracks-the children's section. By a twist of fate, when the final Nazi cry of "Alle Juden raus!" echoed through the camp, each of the girls was hidden by her mother instead of joining what was for many a death march. On January 27, 1945, the date of their liberation and, subsequently, the date celebrated by the three women as their "birthday, " Tova was six years old, Frieda was ten, and Rachel was seven. Nieuwsma, a journalist, assembles the sometimes brutal oral histories of these women from childhood through liberation and the aftermath of displaced persons camps, the often futile search for scraps of information about surviving family, and the difficult decision to emigrate. In the story of each woman's adult life, there is a resurgence of hidden memory and post-traumatic stress; Tova speaks of "existential loneliness" during every holiday, Rachel of her never-ending search for "missing pieces, " and Frieda recalls that "if you cried in the war you were dead...But I can do it now, and it's a precious thing." The photographs of these women with their children and grandchildren are a testament to their strength and to the capacity of the human spirit to survive. Their intensely moving stories are a remarkable gift of insight to the Holocaust years and its implications for all of us."--Publisher description.

ABC News (27 January 2020)

Tova Friedman said she credits her survival on her mother, who opted to never lie to her about the Holocaust and what the Nazis were doing to the Jewish people.

"(My mother) also helped save my mind, not only my life, my mind. Because when she spoke to me ... when she explained what was going on, I understood it. At the age of 4 and 5 ... I didn't know what death was but I sort of knew that you don't come back from whatever death is. ... My mind wasn't as panicked as it could have been," she said.

Friedman's family was forced to move to a ghetto with other Jewish families, later ending up in a labor camp, where her parents hid her in a crawlspace at their home to prevent her from being taken away by the Nazis with other children. From there, she'd see the children from her town separated from their parents and shipped to certain death.

"Every time they moved you to a new place, they would clean up the old place so that nobody could say, ‘Look what you’re doing!’ In fact, at one time, when the Red Cross came to another place, everything was cleaned up," she said.

But as the persecution of Jews accelerated, Friedman and her parents were taken to Auschwitz in a cattle car train.

"You couldn’t lie down. You slept standing," she said. "(My mother) just had her hand around me. … The noise was impossible, the screaming of the people, crying."

When they arrived at Auschwitz, she was told to undress and her hair was cut, as she said she watched women being taken to the crematorium. Later, she was tattooed and sent to a children's barracks. Her new name: 27633 A. She was 5 and a half years old.

She turned 6 at the camp, and recalled realizing it was her birthday when her mother smuggled a piece of bread. The little packet read: "Happy sixth birthday."

The gift came at a cost though -- her mother was severely beaten and Friedman never got to eat that bread.

"I went to the crematorium. ... I knew that I was going. You know why? Because the barrack next to me had gone a few days earlier. I didn't know where they were really going, but it was empty. The barrack was empty. And this, and we were one of the last barracks left," she told Muir.

Her mother, from whom she'd been separated, saw her.

"I hear my name. And I said to myself, 'Who knows my name? This is my name. Must be my mother.' So I hear a voice. I didn't even recognize the voice, but I hear somebody say, 'Where are you going?' And I said, 'To the crematorium.' And they started screaming. And I remember turning to the little girl next to me and I said, 'Why are they screaming? Every Jewish child goes there, so now we're going there,'" Friedman said. "I was a year old when the war broke out. I didn't know anything else."

After getting undressed, she waited but the shower she had been told about never came.

"Hours later, they told us to get dressed," Friedman said. "Coming back was freezing. It was so cold. And I hear my mother's voice again, my name. She says, 'What happened?' And I remember saying it in a very loud voice, 'They couldn't do it this time. They'll do it next time.'"

As the Russians closed in on Auschwitz, Friedman remembered, her mother chose to hide and possibly die instead of joining the Nazi march. The two hid among the dead in the women’s hospital.

"I don’t know how long it took but I heard Germans coming in. … They were running away but they were shooting people who were almost dying anyhow. … I always heard those German boots. Sometimes I have nightmares about those boots," she said.

She waited among the dead, under a blanket, until her mother returned for her. In the meantime, the Germans took tens of thousands of Jewish people with them on a death march to other camps.

"They're gone," she said her mother told her.

Later, the Russians arrived. Friedman, now 81, said she has celebrated Jan. 27, 1945 as her second birthday ever since. Out of the 5,000 children in her town, she said, she was one of five to survive.

In a film recorded by the Russians days after the liberation, children including Friedman and Bornstein, can be seen pulling up their sleeves to reveal the numbers the Nazis had tattooed on them. They showed Muir that image, now in the Museum of Jewish Heritage: A Living Memorial to the Holocaust, in New York City.

"They were telling us, they gave us, like, an order to 'Show us the number. Show us so we could show the world,'" Friedman said. "They liberated us and then they fed us. And, we got some clothing. And, we could sleep in -- regular sleep without fear. And, a week later... they took this picture."