Sylvia Rozines

Sylvia Rozines / Sylvia Perlmutter (F / Poland, 1935).

- KEYWORDS : <Lodz Ghetto> <Liberation of Lodz> -- <France> <United States>

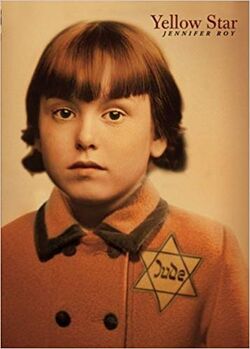

- MEMOIRS : Yellow Star (2006)

Biography

Sylvia Perlmutter was born in 1935 in Lodz, Poland. Under Nazi occupation, the family was forced to live in the Lodz ghetto. When the Jewish children of Lodz were sent to die at Chelmno, Syvia's family smuggled the children from cellar to cellar. When the ghetto was liquidated the entire family went into hiding. On January 19, 1945, Sylvia, her sister, and her parents were liberated from the Lodz ghetto by the Soviets. Syvia, her older sister Dora, and her younger cousin Isaac were three of only twelve children who survived in the ghetto. After the war, the family moved to France and then to the United States. More than 50 years after the events described in the book, Perlmutter Rozines began telling her story to family members.

Book : Yellow Star (2006)

- Sylvia Rozines and niece Jennifer Roy, Yellow Star (Tarrytown, NY : Marshall Cavendish, 2006).

"In 1945 the war ended. The Germans surrendered, and the ghetto was liberated. Out of over a quarter of a million people, about 800 walked out of the ghetto. Of those who survived, only twelve were children. I was one of the twelve." For more than fifty years after the war, Syvia, like many Holocaust survivors, did not talk about her experiences in the Lodz ghetto in Poland. She buried her past in order to move forward. But finally she decided it was time to share her story, and so she told it to her niece, who has re-told it here using free verse inspired by her aunt. This is the true story of Syvia Perlmutter—a story of courage, heartbreak, and finally survival despite the terrible circumstances in which she grew up. A timeline, historical notes, and an author's note are included."--Publisher description.

"More than 50 years after the events described in the book, Perlmutter Rozines began telling her story to family members, starting with her son, Roy's cousin Greg, who told Roy's sister Julia, who told Roy. Roy tape recorded the conversations between herself and Perlmutter Rozines, and used those conversations as the basis for the book ... Yellow Star is written in free verse, after Roy struggled with how to authentically express Perlmutter Rozines' experiences to children in a way that did not seem stiff or detached. The story is told in the first person, as if the child were telling the story herself".

Profile: USHMM

Sylvia Rozines was born Syvia Perlmuter on January 20, 1935, in Lodz, Poland. Her father, Isaac, was a salesman, and her mother, Haya, cared for Sylvia and her elder sister, Dora, who was seven years older.

World War II began when Germany invaded Poland on September 1, 1939. Within only seven days, German troops entered and occupied Lodz. The Germans soon enacted antisemitic laws, including those that required all members of the Jewish community to wear the Star of David on the front and back of their clothing. In February 1940, 160,000 Jews were forced to move into the Lodz ghetto. The ghetto was surrounded a barbed-wire fence which separated it from the rest of the city. Food was scarce, and diseases, like typhus, spread throughout the ghetto. Residents of the ghetto were required to work for the Germans. Isaac delivered flour while Haya and Dora worked in a clothing factory, one of ninety-six factories in the ghetto. Sylvia, along with all other Jewish children, was no longer allowed to attend school.

In January 1942, deportations began from the Lodz ghetto to the Chelmno killing center. In the Gehsperre or “general curfew” deportation of September 1942, the Germans searched for and rounded up the children who remained in the ghetto. When the Germans began searching for children street by street, Isaac found hiding places for himself and Sylvia. Isaac often had to secure a new hiding place every day, and on one occasion, they hid in the city cemetery until Dora was able to tell them it was safe. It was dangerous for Sylvia to go outside alone, so when she was not hiding with her father, she spent most of her time with two other Jewish girls who lived in her apartment building. Since most of their toys had been traded for supplies and food, they invented new games and played with dolls made from old sheets to occupy their time.

In August 1944, the Germans began the liquidation of the Lodz ghetto. The remaining 75,000 Jewish residents of Lodz were told to pack their belongings and report to the train station. The majority of the residents were deported to Auschwitz-Birkenau. A small group of adults were selected to stay to clean the ghetto, Isaac, Haya, and Dora were among them. Isaac was able to sneak Sylvia into a cellar when the guards were not watching. Eleven other children were hidden with Sylvia in the cellar while the adults lived in two factory buildings nearby. In the winter of 1944, German guards discovered the children in the cellar, dragged them outside, and allowed them to live with the adults.

On January 19, 1945, the day before Sylvia’s tenth birthday, 800 Jews, including Isaac, Haya, Dora, and Sylvia, were liberated from the Lodz ghetto by the Soviet army. Realizing antisemitism was still rampant in Poland, the Perlmuter family relocated to a displaced persons camp in Germany. From there, they made their way to Paris, where Haya’s brother was living. Sylvia spent her teenage years in Paris until she immigrated to the United States in 1957.

Sylvia married David Rozines, a Holocaust survivor from Poland, in 1959, and they settled in Albany, New York. They had a son and two grandchildren. Sylvia worked in the New York school system for 24 years. Following David’s death, Sylvia relocated to the Washington, DC, area and is a volunteer at the Museum.

The Town Courier, Gaithersburg (6 July 2018)

History came calling to the Kentlands Clubhouse on June 14 when Holocaust survivor Sylvia Perlmutter Rozines lent a voice to her story vividly captured in the book “Yellow Star,” written by her niece, Jennifer Roy.

Born in 1935, Rozines was four-and-a-half years old when the Germans invaded her birthplace of Lodz, Poland on Sept. 1, 1939. Lodz was the second largest Jewish community in prewar Poland, and an important center for industry. Six years later, on Jan. 19, 1945, Rozines was on the cusp of her 10th birthday when the Soviets liberated the Lodz ghetto. More than 160,000 Jews had been isolated in the city’s northeastern section; only about 800 remained. “Of the 800, a handful of children survived, and I was one,” Rozines said.

With courage and grace, she shared a montage of memories sequencing her life as a young child in the German-occupied ghetto. “It was a happy time before the war, we had a good life. My mother was a great cook and we had beautiful clothes and toys, so this is why we had so many things to sell for money and food.”

“Life was very sad (in the ghetto),” said Rozines. “Even the birds didn’t come because there was no food on the ground, nothing to eat.” The effects of starvation, disease and overcrowding are reflected in “Yellow Star” where apartments cramped with multiple families are described as “boxes of grief and fear,” and Rozines, a growing girl, ponders, “I have my eighth birthday while in hiding and then my ninth. Time goes on, and so do we.” Rozines said people still hoped, “It’s not going to last long. The will of living was how to survive.”

“When the Germans took the children away with the propaganda that they were going to camps, many parents gave the children because they couldn’t watch them starve,” said Rozines. Rations such as “a little soup, which was mostly water, and a piece of bread” were given to workers and “sometimes, by the time your turn came, the food was gone.” In the wintertime it was very tough. … They stopped giving us coal, so we used some furniture at the end in the oven” for fuel.

“Life was very hard. Young boys ages 12 or 13 had the job to pick up the bodies. I saw many bad things like the mothers giving up the children.” Parents were told they could keep one child and were ordered to decide which, boy or girl, would be given away. “My father hid the boy behind the armoire and told him to stay there. Then my father imitated a German and ordered everybody to come out. The boy remained in place. This family survived.”

“I had a very courageous father,” said Rozines. “I’m sitting here because my father saved my life many, many times.” Isaac Perlmutter sought a variety of hiding places to protect his family because “the Germans used to find the places,” said Rozines. Near their apartment’s backyard was a cemetery where her father dug a hole and hid her covered with grass for 24 hours. She said she started to cry, “‘I don’t want to die.’ I lived in fear all the time wondering ‘when are they going to come and grab me?’”

When the Germans decided to liquidate the ghetto, Rozines said everyone was told they could take one bottle of water and one belonging. “So, they chose 800 people. The leader was a very horrible man. He did the selection of who would stay and who would go. We didn’t know anything, but my father had a premonition at the last minute about going to the train. He had investigated a cellar, a place to hide.” She and others hid in the cellar for “a period of time.” After the ghetto was liberated, her father “paid someone to get us across the border into Germany” and Roy writes, they “remained in a detainment camp for a few months … received permission to go to Paris, France … where Sylvia spent her teenage years.” Rozines came to America in 1957.

A fence crowned with barbed wire cordoned off the ghetto. Rozines smiled as she recalled the stark contrast on the other side of the fence of geraniums at an apartment window. “I said to myself, ‘One day, when I’m liberated, I’m going to have flowers, if I survive.’” To this day, on Mother’s Day every year, her son brings her a pot of geraniums.

During the question and answer period, resident Jacob Opper stood up and said, “Sylvia, your story is mine.” Opper was six years old when he and his family fled Poland and were ultimately deported to Siberia when they refused to become Russian citizens. “We knew we could never leave Russia if we became citizens.”

Attendee Mina Parsont said, “I was one of the hidden children too.” It was many years before she could talk about her experiences because nightmares would come, but she said it is important to speak “because in order to understand history you have to know not only the present, but also the past and never forget.” Kentlands resident Mel Swerdloff reflected, “Everybody’s story is different, but they’re all the same—they all survived.”

“When I came to America, I put away my story like you put something in a drawer and you lock it,” said Rozines. She considered herself shy until her husband passed away in 1999. “I found myself by myself, and I had to take care of myself, and little by little I came out.” She started volunteering and speaking at the Holocaust Museum in D.C. A profound excerpt from “Yellow Star” reads, “I have always been shy and quiet, unlike other children … perhaps this is one reason I am still here in the ghetto. I know how to be invisible.”