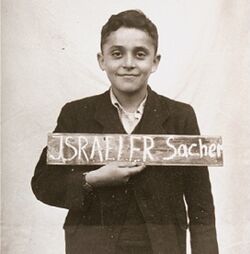

Sacher Israeler (M / Poland, 1931), Holocaust survivor

Sacher Israeler (M / Poland, 1931), Holocaust survivor

- KEYWORDS : <Poland> <Tarnow Ghetto> <Plaszow> and other camps -- Liberated at Flossenburg

Biography

Born in Krakow, Poland, on January 19, 1931, Steve (formerly Sacher) Israeler was the youngest of six children. His father, David, had a textile business on the main street of the city’s Jewish quarter, and his mother, Regina (Ryfka) (née Wolf), was a housewife. His older siblings were Miriam, Rose, Janka, Helen, and Walter (Zev).

As a child, Steve studied at a Polish school. He was just about to enter the third grade when Germany invaded Poland in September 1939. His father shaved his beard in order to avoid being stopped on the street. His business was eventually confiscated, and his supplies were sent to Germany. Upon learning that Krakow was to be made Judenfrei, the Israeler family moved to nearby Tarnow, where Regina’s sister lived. Eventually the Nazis undertook an Aktion, during which they shot people in the street. Steve’s parents and two older sisters were among those killed.

After the Aktion, Steve, his brother, and his remaining sisters were put in the Tarnow ghetto. Steve worked in a woodworking factory while his siblings worked in a factory outside the ghetto making uniforms and leather accessories. When the liquidation of the ghetto began, Jews were sent to Sobibor and other places. “I kept on surviving,” Steve says. At one point, the infamous SS officer Amon Göth selected Steve for deportation because of his youth and small size. Steve told him that he should be allowed to remain in the ghetto because was a good worker; Göth allowed him to stay. Later, when there were only about 300 Jews left in the ghetto, the German commander lost his horse driver. Steve told him that he was a horse driver and was again spared deportation.

When there were only about 150 Jews left in the ghetto, they were taken to Plaszow. Steve knew there would be additional roundups because so many children were there and because the camp was filled with filth and lice. He volunteered to go to Mielec, where he was put to work in an old airplanefactory. There were about 3,000 Jews there from other ghettos and camps as well as Polish Jewish POWs.

From Mielec, the Germans took Steve and other prisoners to Wieliczka, near Krakow. There, they were put on trains. He remembers at one point being stopped at Auschwitz for a day or two, but he and his fellow prisoners did not get off the train there. On August 4, 1944, they arrived at the camp Flossenbürg. They were the first Jews to arrive there. Steve once again worked in a factory, this time making parts for airplanes.

About a week before the Flossenbürg was liberated in April 1945, the guards marched prisoners out of the camp. Steve was among those placed on a train. After the train moved a few kilometers, American planes flew over and fired at the train, hitting the engine and some of the prisoners. After the attack had ended, the guards brought a new engine. The train continued for a few kilometers until the Americans attacked again, hitting the engine and more prisoners. After this cycle had continued for four days, the remaining prisoners, of whom Steve was one of the youngest, began marching toward Dachau.

After seven days of marching, on April 23, 1945, the prisoners noticed that the guards had left them. They decided to go in to town to see what was happening. They saw a German officer who wanted to surrender, so they took him prisoner. They then saw tanks with white stars. Thinking they were Soviet soldiers, Steve began shouting at them in Russian. When the soldiers threw packages of food to the newly freed prisoners, Steve warned his friends not to eat because they might get sick after having gone hungry for so long. One soldier came out of a jeep and began speaking in Yiddish. The former prisoners learned that he was a young Jewish man from New York City. The soldier began to cry, and then so did the other men. Fearing a German counterattack, the soldier warned them to go back.

Steve had a slight wound and was taken to an American field hospital. He spent the next few months with the 90th Infantry Division and then went to the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration home Kloster Indersdorf. In January 2016, Steve was at the United Nations to see an exhibition about Kloster Indersdorf. There, he met a former member of the 90th Infantry who was 91 years old.

After a very short time at Kloster Indersdorf, Steve learned that his cousins and aunts had survived the war. He joined them, and the family eventually made its way to Paris. Because he was with family and not in a displaced persons center, Steve had difficulty at first to obtain a visa to theUnited States. In 1947, he received a visa for Canada. He went to Montreal and then Toronto, where he had a cousin. On September 4, 1949, he moved to NewYork, where he has lived ever since. He worked for his family’s import business and is now retired.