Category:Girls of Room 28 (subject)

Brundibar

When in July 1943 rehearsals for the opera Brundibar began, girls of Room 28 were among them. Ela Stein (now Weissberger) played the cat, Maria Mühlstein often the sparrow and several times she played Pepicek's sister Aninka, on the side of her brother Eli. Handa Pollak (now Drori) played sometimes the dog and Anna Flachová (later Hanusová) sang in the choir of the school kids, and once she even played Aninka. All of the girls knew the opera by heart, and songs from Brundibár were often heard in Room 28.

Book : Girls of Room 28 (2004), by Hannelore Brenner

January 27th is Holocaust Memorial Day, an annual commemoration of those who were persecuted and systematically murdered under the Nazi regime, remembered on 27 January as it marks the liberation of the largest Nazi death camp, Auschwitz-Birkenau. The theme for the 2018 Holocaust Memorial Day is ‘The Power of Words,’ looking at how language can impact societies, both positively and negatively.

To write about the Holocaust from a girl’s eye view, my first thought was to reflect upon Kindertransport and the estimated 10,000 children that were saved between December 1938 and August 1939. Girl Museum has a fantastic exhibition, titled Madchen Der Kindertransport, that explores the experience of girls. As Kindertransport has already been explored at Girl Museum, I chose to focus on female friendship triumphing during this tumultuous time, especially focusing on the Theresienstadt “camp-ghetto.”

Hannelore Brenner wrote the stunning The Girls of Room 28: Friendship, Hope and Survival in Theresienstadt in 2009, meeting 10 survivors of the Holocaust who were young girls living in Girls Home L410, Room 28 in Theresienstadt between 1942 and 1944, and interviewed them about their experience. Written in chronological order over the period between 1942 and 1944  and using both oral history testimonies and the secret diaries that some of the girls kept during their time in Theresienstadt, The Girls of Room 28 gives a fascinating insight into the unique daily lives of these young girls living in Theresienstadt.

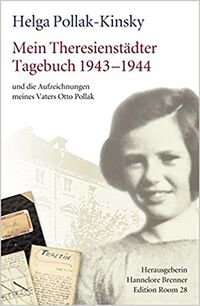

The 10 survivors Brenner met were between 12-14 years old during their time at Theresienstadt, so at the time of publication were mothers and grandmothers in their seventies. Of the approximately 50 girls that resided in the Girls Home in the Theresienstadt concentration camp between 1942 and 1944, only 15 survived. Of these were Eva Weiss Gross, Hanka Wertheimer Weingarten, Judith Schwarzbart Rosenzweig, Eva Winkler Sohar, Marta Frohlich Mikul, Vera Nath Kreiner, Ela Stein Weissberger, Miriam Rosenzweig Jung, Eva Eckstein Vit, Eva Mer, Handa Pollack Drori, Helga Pollak Kinsky, and Anna Hanusova-Flachova.

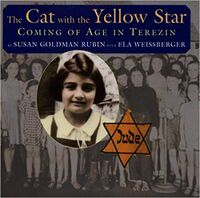

Theresienstadt “camp-ghetto” was located in German-occupied Czechoslovakia, between November 1941 and 1945. As Theresienstadt was, strictly speaking, not a concentration camp when compared to its counterparts, Theresienstadt served as an important propaganda function for the Germans. Portrayed as a ‚Äòsettlement‚Äô and even a ‚Äòspa town‚Äô in the infamous propaganda film, cultural and religious life was interrupted as it gave the impression of having better living conditions that were realistically the case. The 10 girls in The Girls of Room 28 were consequently involved in the children’s opera Brundib√°r. Composed by Hans Kr√°sa with a libretto by Adolf Hoffmeister, the opera was performed by the children living in Girls Home in Theresienstadt. Ela Stein writes about the experience of performing in Brundib√°r in her diary, ‚ÄòWhen my turn came, I shook with fright at the thought that I wouldn‚Äôt sing well enough. But then Rudi Freundenfeld said to me, ‚ÄúYou know what? You‚Äôll play a cat.‚Äù A cat in a children‚Äôs opera? That was something extraordinary‚Äô. Brenner touches upon this in The Girls of Room 28, where she says that ‚Äòwhile enduring unimaginable suffering, the children of Theresienstadt also studied, played, danced, sang, did gymnastics, created art, wrote poems, and appeared in theatrical performances‚Äô (p.14).

What struck me when reading The Girls of Room 28 is the friendship that the girls established, and how this friendship emotionally carried them through their years in the camp. Marianne Rosenzweig, Theresienstadt survivor, writes “I consider the time I spent in Room 28 the best time in Theresienstadt. Although we were young, and although hunger, cold and fear defined our lives, we remained honest and decent and always had high moral values. And we developed very deep friendships of that sort that would have scarcely been possible under normal circumstances” (p.12).

Hannelore Brenner‚Äôs The Girls of Room 28: Friendship, Hope and Survival in Theresienstadt is a striking tale of friendship and hope being an important factor of emotionally surviving the adversity of the Theresienstadt “camp-ghetto.” It is clear to see why The Girls of Room 28 was praised as being a ‚Äòbeautiful evocation of heartwarming friendship in the darkest of times.‚Äô Using oral history testimonies of the 10 survivors was a powerful personification and individuality of an unimaginable experience for a ¬†young girl to endure. As Girl Museum works to spotlight the unique histories of young girls as an ‚Äòinformation platform for socio-cultural dialogue about girls around the world in the past and present‚Äô, it was enlightening to read and review Hannelore Brenner‚Äôs The Girls of Room 28: Friendship, Hope and Survival in Theresienstadt

Girls of Room 28

Victims

- Hana Epstein (1930-1944)

- Eva Fischl (1930-1944)

- Irena Grunfeld (1930-1944)

- Ruth Gutmann (1930-1944)

- Marta Kende (1930-1944)

- Anna Lindt (1930-1944)

- Hana Lissai (1930-1944)

- Olga Lowy (1930-1944)

- Zdenka Lowy (1930-1944)

- Ruth Meisl (1929-1944)

- Helena Mendl (1930-1944)

- Maria Mühlstein (1932-1944), Holocaust victim.

- Bohumila Polacek (1930-1944)

- Ruth Popper (1930-1944)

- Ruth Schachter (1930-1944)

- Pavla Seiner (1930-1944)

- Alice Sittig (1930-1944)

- Jirinka Steiner (1930-1944)

- Erika Stranska (1930-1944)

- Emma Taub (1930-1944)

Survivors

Featured in Brenner's book are: Eva Weiss Gross, Hanka Wertheimer Weingarten, Judith Schwarzbart Rosenzweig, Eva Winkler Sohar, Marta Frohlich Mikul, Vera Nath Kreiner, Ela Stein Weissberger, Miriam Rosenzweig Jung, Eva Eckstein Vit, Eva Mer, Handa Pollack Drori, Helga Pollak Kinsky, and Anna Hanusova-Flachova.

- Marianne Meyer / Marianne Deutsch (1930-2014)

- # Anna Hanusova / Anna Flachova (F / Czechia, 1930-2014)

- # Marta Mikulová / Marta Fröhlich (1928-2010) Mikul

- Eva Heller (1930)

- Eva Kohn (1930)

- # Evelina Merova / Eva Landova (1930) (Mer)

Memory of Nations

Evelina Merová was born on Christmas in 1930. The original name of her father was Löwy but he changed it to Landa. Evelina Merová was henceforth generally known to people as Eva Landová. In 1939 - it was by the time she attended the second year of an elementary school called “U Studánky” - she was made to realize her Jewish roots for the first time. It was in connection with the Nazi occupation of Czechoslovakia. Her life gradually began to change. Laws discriminating Jews were introduced in the country and Evelina could no longer go to school or play on a playground. The family was moved to a flat where they lived together with three other Jewish families. She personally perceived as her first great loss, when her canary was taken away from her as it was illegal for Jews to possess pets. On June 28, 1942, they had to get on a transport to the Theresienstadt ghetto. In Theresienstadt, she was placed on the so-called Kinderheim L 410, in room Nr. 28. In December 1943, she went straight from hospital (she was recovering from encephalitis) on another transport, this time to Auschwitz. Her transport was one of three, which were special in a way. The Jews from these three transports weren’t subjected to the notorious “selection” that used to take place right at the unloading ramp in Auschwitz. Instead, they were sent directly to the “family camp” B-II-b. The records of the inmates from these transports said that they were to remain in Auschwitz for 6 months and afterwards would receive “SB” or “Sonderbehandlung” (special treatment), which meant that they would be gassed. Evelina’s father died of tuberculosis in Auschwitz. Evelin and her mother passed Mengele’s selection and were sent to forced labor. They wouldn’t come back to Auschwitz. They also had to dig trenches. In November 1944, her mother died of starvation and exhaustion and Evelina was left alone. By the time of her mother’s death, she had no boots and her feet were strongly frostbitten. Therefore, she was supposed to be sent to the gas chamber but after a long and strenuous death march, they found out that the railway station no longer exists and therefore they returned back to the camp. Evelina was tied to the bed and she was running the risk of a feet amputation. By the end of January 1945 the German commanders hurriedly left the camp and they tried to murder the inmates with phenol shots and rifle-butt blows to the head. However, a portion of the inmates survived. The women were found by the soldiers of the advancing Red Army and they were taken to the Soviet field hospitals. They boarded a train which took them to the town of Syzraň in the Kujbyševo district. On that train, Evelina met a Jewish child doctor by the name of Mero, who adopted her. Evelina spent the following part of her life in Leningrad (today’s Saint Petersburg), where she graduated in German studies, married and gave birth to two children. In 1985, her husband died and after she retired in 1995, she finally returned to her former home, something she had yearned for many years. Her son, who emigrated from the Soviet Union, presently lives in Frankfurt am Main and her daughter in Saint Petersburg.

- # Vera Kreiner / Vera Nath (1930)

See The book

- # Hana Drori / Handa Pollak (1931)

Memory of the Nations

Hana Drori, née Pollaková, was born on 4 November 1931 in Prague into a Jewish family. She grew up in Olbramovice where her father’s family owned a farm. Following her parents’ divorce Hana stayed with her father in Olbramovice while her mother lived in Prague. In 1939 the family farm was confiscated and Hana followed her father to Prague. In October 1941 her mother was deported to the Lodz ghetto; in December 1941 her father went to the Terezín ghetto. Hana followed him there in July 1942. She lived in children’s home No. L410 in care of governesses. Hana’s father had married one of the governesses - Ella so-called Tella. In the fall of 1944 her father was deported to Auschwitz. Hana’s and Tella’s turn came in October 1944. After a week in Auchschwitz-Birkenau both were selected for work in the camp Oederan in Germany. From October 1944 until spring 1945 they worked in an ammunition factory. At the turn of March and April the camp was evacuated and Hana ended up in Terezín again where she lived to see liberation. In May 1945 she returned to Prague only to find out her father died shortly before the end of the war and that she was one of the few survivors from the broader family. She lived in Prague with her father’s wife Ella Pollaková, studying at a grammar school. In 1949 she joined a Zionist group and moved to Israel. There, she settled down in HaHoterim kibbutz, worked in agriculture and started a family. In the 1970s and 1980s she and her husband lived in Africe. Hana Drori lives in Israel and makes regular visits to the Czech Republic.

- # Helga Pollak-Kinsky (F / Austria, Czechia 1930)

- # Miriam Jung / Miriam Rosenzweig (1929-2012)

- # Judith Rosenzweig / Judith Schwarzbart (1930-2019), Holocaust survivor.

- # Ela Weissberger / Ela Stein (1930-2018), Holocaust survivor.

- Eva Stern (1930)

- # Hanka Weingarten / Hanka Wertheimer (F / Czechia, 1929-2018), Holocaust survivor.

- # Eva Zohar / Eva Winkler (1930-2014) (Sohar?)

- < # Eva Eckstein Eva Vit >

Pages in category "Girls of Room 28 (subject)"

The following 5 pages are in this category, out of 5 total.

1

- Hanka Weingarten / Chana Wertheimer (F / Czechia, 1929-2018), Holocaust survivor

- Anna Hanusova / Anna Flach (F / Czechia, 1930-2014), Holocaust survivor

- Helga Pollak-Kinsky (F / Austria, 1930), Holocaust survivor

- Ela Weissberger / Ela Stein (F / Czechia, 1930-2018), Holocaust survivor

- Maria Mühlstein (F / Czechia, 1932-1944), Holocaust victim