Category:Enochic Studies--Pre-Modern

Enochic Studies in Pre-Modern Times--Works and Authors

< Pre-Modern -- 1400s -- 1500s -- 1600s -- 1700s -- 1800s -- 1850s -- 1900s -- 1910s -- 1920s -- 1930s -- 1940s -- 1950s -- 1960s -- 1970s -- 1980s -- 1990s -- 2000s -- 2010s -- ... >

Overview

The Legacy of Second Temple Judaism

Enochic traditions were widespread in the Second Temple Judaism and played an important role in the many Jewish groups of the time, especially in apocalyptic circles, at Qumran and in the nascent Jesus movement.

With the end of the second Temple period, after the destruction of Jerusalem and the Bar Kokhba revolt, Enochic traditions survived and developed in late antiquity and the early Middle Ages in five major settings, that is, in the religious context of Judaism, Christianity, and Islam, and in the more secular contexts of ancient chronography and of the Hermetic philosophical tradition.

Enoch between Christianity and Rabbinic Judaism

- See also Enoch in Christianity, and Enoch in Judaism

"Because the early church arose in the circles of apocalyptic Judaism, the Enochic texts and traditions were known and significantly influenced early Christian thought" (Nickelsburg, 2001, p. 82-83). The status of "secret texts" may be responsible for the paucity of explicit quotations of Enoch the prophet as scripture; such quotations are limited to a few documents, notably, the Letter of Jude (14-15), the Letter of Barnabas and the Testaments of the Twelve Patriarchs. Yet the presence of Enochic is pervasive in the earliest Christian literature, and Enochic traditions seem to have played a central role in the formation of earliest Christian theology, especially concerning the doctrines of the origin of evil, demonology, and the Son-of-Man Christology.

The writings attributed to Enoch continued to enjoy a quasi-normative status in the first three centuries of Christianity (see Lawlor 1897; Vanderkam 1996; Nickelsburg 2001). Enochic traditions were referred to as authoritative, among others, by Justin Martyr (Second Apology 5:2; ca. 150 CE), Athenagoras (Plea for the Christians, 177 CE), Irenaeus, Clement of Alexandria and with particular enthusiasm, by Tertullian (De cult. Fem.; De idolatria; ca. 210 CE).

In the first half of the 3rd century Origen still referred to Enoch as a prophet and to the Enoch texts as scripture. From his writings however we learn that some within the Church now openly challenged the authenticity of Enochic texts.

From the mid-fourth century, the attitude among Christians became decidedly more guarded, as already attested in the 39th Paschal letter by Athanasius (367 CE): “Who has made the simple folk believe that books belong to Enoch, even though no scriptures existed before Moses?" (Brakke 2010). Skepticism and irony soon left room to open rejection and hostility. The Apostolic Constitutions (6:16, ca 380 CE) condemned the book of Enoch as “pernicious and repugnant to the truth.” Jerome referred three times to the book of Enoch as “apocryphal” (Comm.in Ep. Ad Tit. 1.2,ca. 387 CE; De viris illustribus 4, 393 CE; Brev. In Ps. 132:3, ca 400). Augustine also twice rejected the text as "apocryphal" (De civitate Dei 15:23, 18:38, ca.420 CE).

Two factors seem to have contributed mostly to the demise of Enoch:

(a) First, the silence (and hostility) of the early Rabbinic tradition against Enochic traditions. "The Enochic myth of angelic descent was divorced from the interpretation of Gen 6:1-4... [and] the authority of Enochic literature was invalidated " (Reed 2005, 234). In Gen. R. v. 24 Enoch is held to have been inconsistent in his piety and therefore to have been removed by God before his time in order to forestall further lapses. The miraculous character of his translation is denied, his death being attributed to the plague. The success of the rabbis in eradicating Enoch from their own tradition affected the Christian attitude toward Enoch. The Christian claim of being the fulfillment of the ancient religion of Israel could be diminished by an excessive emphasis on traditions that the “rival” Jews considered marginal and heretical.

(b) Second, Enochic traditions were heavily used in the “heretical” Christian movements of Judeo-Christians, Gnostics and Manicheans. The presence of Enochic traditions in the Judeo-Christian literature (esp. in the Christian Testaments of the Twelve Patriarchs and in the Pseudo-Clementine corpus, Homily 8:10-20) is conservative of the earliest Enochic roots of the Jesus movement. In Gnostic and Manichean circles instead the approach was more creative and Enochic traditions provided the foundations on which new theological ideas on the origin of evil were developed. The vitality demonstrated especially in Manichaeism likely contributed to the growing suspicion with which many “orthodox” Christians were now looking at Enochic traditions.

As a results of these tensions, between the 4th and 5th century, the book of Enoch passed out of circulation in the church in both the East and the West, with the Ethiopian church and the Slavonic Church remaining the two most conspicuous exceptions.

The Case of the Ethiopian and the Slavonic Church

When Christianity spread in Ethiopia in the mid-fourth century, the authority of 1 Enoch was recognized by the Ethiopian church and in the following centuries the text (along with the other "biblical" texts) was translated into Ethiopic. At the time of the establishment of the Ethiopian Church 1 Enoch still enjoyed vast popularity in Egypt; hence its presence in Ethiopia is not surprising. What was unique, was the lasting success of the book. Several factors contributed to the survival of 1 Enoch in Ethiopia. First, the text well adapted to the new environment, where it played an important role in the absorption and "christianization" of ancient pagan beliefs about the presence of angels and demons. Second, the Ethiopian Church interacted with a local form of Judaism which was not governed by the "rabbinic" rules that elsewhere shaped the formation of the "Hebrew Bible." Finally, the controversies against Gnostics and Manichaeans never dominated the theological debate in Ethiopia, nor did the imperial agenda in a region that was outside the boundaries of the Roman Empire.

There were indeed discussions in Ethiopia also about the authority of the text, yet it continued to be copied and preserved over the centuries, until its canonicity was definitively established in the 15th century as a result of the reform of Emperor Zar'a Ya'qob, who reigned from 1434 to 1468 and made the book of Enoch a centerpiece in his apologetical interaction with Judaism. The earliest mss of 1 Enoch date from that period.

The influence of Enochic traditions is noticeable in the major products of Ethiopian theology, from the Kebra Nagast ("The Glory of the King") to the Mashafa Mestira Samay wameder ("The Book of the Mysteries of Heaven and Earth") and the "Mashfa Seneksar ("The Book of Saints"). The 15th-century homelitical work Mashafa Milad ("The Book of Nativity") also contains extensive extracts from 1 Enoch, particularly the Parables; see Kurt Wendt, Das Mashafa Milad (Liber Nativitatis) and Mashafa Sellase (Liber Trinitatis) des Kaisers Zar'a Ya'qob (Louvain: Secretariat du Corpus SCO, 1962, 1963).

Enochic traditions in the Slavonic Church present a similar case. 2 Enoch was probably composed in Greek (or perhaps freely translated from some Hebrew Urtext), and from the Greek was translated in Slavonic after the 9th century. The Slavonic Church preserved it along with the other "biblical" texts, which also included several apocalyptic texts of Second Temple Judaism, notably, the Apocalypse of Abraham, 3 Baruch, and the Ladder of Jacob. For some centuries, until the end of the 15th century, 2 Enoch enjoyed in the Slavonic Church an ill-defined semi-canonical status, similar to that of 1 Enoch in the early Ethiopian Church. The document was included in the Palaea Interpretata, a 13th-century Slavonic collection containing fragments of biblical texts (from Genesis to Kings) together with apocryphal, exegetical, cosmographical, and anti-Judaic polemic texts.

The reasons for the preservation of 2 Enoch in the Slavonic Church are not clear, due also to the lack of documentation. It is possible that the strength of dualistic tendencies contributed to the success of the document. At the end, 2 Enoch failed to gain full canonical status when the first complete ms of the Slavonic Bible was completed (the Gennadi Bible, Генна́диевская Би́блия, 1499), followed by the first printed edition in 1581 (the Ostrog Bible, Острожская Библия, 1581). However, excerpts from 2 Enoch were still included in the very popular and influential Great Menaion Reader (Великие Четьи-Минеи, 1541; 2nd ed. 1552), the official Russian Orthodox menologium compiled under the supervision of Metropolitan Macarius of Moscow.

The Ethiopian and the Slavonic Church offer two examples of preservation of ancient Enochic material according to a similar trajectory that however ended up with opposite results in the 15th century. In Ethiopia the reform of Emperor Zar'a Ya'qob resulted into a strengthening of the “canonical” status of 1 Enoch, while in the Slavonic Church the publication of the Bible marginalized 2 Enoch, relegating the document to a non-canonical status.

The Hermetic tradition

The connection between Enoch and Hermeticism goes back to the beginnings of the movement in Hellenistic times and significantly contributed to the preservation and transmission of Enochic traditions, from late antiquity to modern times. As a pre-deluge patriarch Enoch was seen as a witness and representative of the primeval religion and wisdom of humankind.

According to the Pseudo-Eupolemos, Enoch had to be identified was the Titan Atlas who was said by the Greeks to "have discovered astrology" (the fragment is recorded in Eusebius' Praeparatio Evangelica 9.17.9: "The Greeks say that Atlas discovered astrology. Enoch and Atlas are the same")

In the 3rd-4th century, Hermetic author Zosimos of Panopolis presented the art of alchemy as the core of ancient pre-deluge science (Fraser 2004). It was one of the secret knowledges taught by the fallen angels and inscribed after the Flood in the Book of Chemes. The assonance with the name of Ham, the son of Noah and descendent of Enoch, betrays the Jewish-Hellenistic origin of these traditions.

Zosimus' marriage of Enochic traditions with the mythic account of the origins of alchemy prepared the path for the identification of Enoch with the Egyptian god of knowledge wisdom and writing, "the three times great" Thoth, whom the Greeks viewed as the divine equivalent of their own "thrice-great" Hermes (cf. Plato, Phaedrus 274d, and Philebus 18b-d).

In the 13th century, the Franciscan monk Roger Bacon reported that some identified Enoch with "the great Hermogenes, whom the Greeks much commend and laud," attributing to him "all secret and celestial science" (Bacon, Secretum secretorum et notulis). In similar terms, the Syrian chronographer Bar Hebraeus recorded the ancient Greeks' belief that Henoch-Hermes "made manifest before every man the knowledge of books and the art of writing" and invented "the science of the constellations and the course of the stars" (Bar Hebraeus, Historia compendiosa Dynastiarum).

The Return of Enoch in Jewish tradition

- See also Enoch in Judaism

As the classical Rabbinic era came to an end, we see an impressive reemergence of Enochic traditions. "These traditions exhibit no discernable connection with early Enochic pseudepigrapha: they appear to have arisen independently from the exegesis of Gen 5 and/or from the development of other traditions about Enoch" (Reed 2005, 234). According to Targ. Pseudo-Jonathan (Gen. v. 24) Enoch was a pious worshiper of the true God, and was removed from among the dwellers on earth to heaven, receiving the names (and offices) of Meṭaṭron and "Safra Rabba" (Great Scribe).

Enochic traditions played a very important role especially in the Sefer Hekaloth (or 3 Enoch, probably composed in the 8th cent. CE), where the emphasis was now on Enoch’s metamorphosis into the archangel Metatron. “Despite the remarkable points of contact between (this) work and earlier Enochic literature, there is little to suggest that that earlier literature would have been available”; an examination of the material seems rather to indicate that the author had “a considerable body of material from the Second Temple period available, some in written form, some in oral form” (Himmelfarb 2014).

References to Enoch are then found in Kabbalist literature--in Sefer ha-Zohar by Moses de Leon and in Perush 'al ha-Torah by Menahem Recanati (13th century). Even in this case, we cannot talk of a direct relations with the ancient writings attributed to Enoch. The Zokar speaks indeed of a "Book of Enoch" on several occasions, but it is a book "preserved in heaven, which no eye can see" (I 37b).

Enoch in the Early Islamic tradition

- See also Enoch in Islam

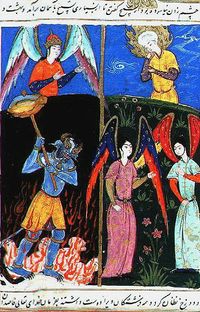

There is an ancient tradition in Islam that identifies Enoch with the quite mysterious figure of the prophet Idris (Erder 1990). Idris is mentioned twice in the Qu'ran: (a) in sura xix. 57 as a "man of truth and a prophet," who lived in the generations of Adam, and was "raised to a high place"; and (b) in sura xxi. 85 as a model of "patience." Nothing in the text actually suggests that Idris was another name (or title) for Enoch. Such an identification however was soon developed in Islamic tradition. The quite obscure reference to the "elevation" of Idris was taken as a reference to the "ascent" of the patriarch to heaven.

The identification of Idris with Enoch allowed Islamic interpreters to use Jewish traditions in the construction of the composite figure of Idris-Enoch (Alexander 2000). At the turn of the 10th century Muhammad ibn Jarir al-Tabari's History (I 166-179) and Al-Masuri's Meadows of Gold provide evidence of the antiquity of these traditions. According to Tabari, "some of the Jews say that Enoch, that is Idris, was born to Jared. God made him a prophet after 622 years of Adam's life had passed. Thirty scriptures were revealed to him. He was the first to write after Adam, to exert himself in the path of God, to cut and sew clothes, and the first to enslave some of Cain's descendants. He inherited from his father Jared that which his forefathers had bequeathed upon him, and had bequeathed to one another. All of this he did during the lifetime of Adam."

Since Enoch was identified with Hermes, the figure of Idris also was assimilated to the Hermetic tradition. By the time of Abdallah ibn Omar al-Baidawi in the 13th cent. the character of Idris/Enoch had taken many of the features already attributed to Enoch in Hermeticism and in the Christian chronographic tradition (Bar Hebraeus). According to the Arab geographer Ibn Battuta (14th cent.), Hermes was also known by the name of Khanukh [Enoch], that is, Idris; it was Enoch-Hermes-Idris who introduced the science of astronomy, foretold the deluge, and built the pyramids, "in which he depicted all the practical arts and their tools, and made diagrams of the sciences."

The Chronographical tradition

The rejection of 1 Enoch from the Christian canon of the major Christian Churches and the loss of the entire text of 1 Enoch did not imply a complete disappearance of Enochic traditions in Christianity.

First of all, the figure of Enoch remained part of the received "canonical" scriptures. Traditions related to Enoch were also mentioned in non-canonical texts preserved by the Church, notably, the Book of Jubilees, and the Testaments of the Twelve Patriarchs, but also the Life of Adam and Eve, the Testament of Abraham, and others. Of special relevance for its popularity was the Latin translation of the Testaments of the Twelve Patriarchs completed in 1242 by Robert Grosseteste, Bishop of Lincoln. England.

Second, the Christian liturgy contained numerous allusions to Enoch and Enochic traditions. For example, the ancient Rituale Romanum explicitly referred to Enoch together with Elijah in a prayer for the dying: Libera, Domine, animam servi tui (ancillae tuae), sicut liberasti Henoch et Eliam de communi morte mundi. Amen. (Breviarius romanus, titulus V, caput 7: Ordo commendationis animae).

Finally, starting with Julius Africanus (Chronographia, ca. 221 CE), sections of the Book of Watchers had been incorporated in the tradition of Christian chronography (Adler 1989). At the turn of the 5th century both Pandorus and Annianus of Alexandria used Enochic traditions to supplement the history and chronology of Genesis. At the beginning of the ninth century, George Syncellus reused and edited the Enochic extracts from Pandorus. Syncellus considered the book of Enoch “apocryphal, questionable in places … contaminated by Jews and heretics,” and yet more historically reliable than other available sources, like Berossus or Manetho. The last known quotations of Enochic material are in the 12th-century chronographies of Michael of Syria (based on Annianus) and George Cedrenus of Byzantium (based on Syncellus).

@2014 Gabriele Boccaccini, University of Michigan

Pages in category "Enochic Studies--Pre-Modern"

This category contains only the following page.