Category:Black King (subject)

Black King

Abstract

According to the Gospel of Matthew, wise men (Magi) from the East come to Jerusalem seeking “the king of the Jews.” The term “magus” (plural magi) was generally applied to dream interpreters, astrologers, or sorcerers from the area of Persia (modern Iran). Accordingly, on sarcophagi, in frescoes, or within by mosaics, these Persian magi were distinguished by red Phrygian caps ascribed to those from the East.

Although the biblical text does not specify how many magi were present, they were thought of as the three kings or the three wise men because they brought three gifts to Jesus. By the 6th century CE, they had been named Caspar (or Jaspar), Melchior, and Balthazar.

While magi were understood to be wise men from the East, one magus became regarded as “black.” As early as the 8th century CE, an Irish text described Balthazar as fuscus, a Latin word meaning “dark” or “swarthy.” Yet, this may have been a description not of his skin color but only his hair and beard.

By the 13th century in European Christian art, one of the Adoration Magi began to be depicted as a "Black King."

Exactly how and when this happened is debatable. It seems that Cologne, Germany played a leading role in creating this image. In June 11, 1164 the Emperor Frederick Barbarossa sacked Milan [Italy]. Among his most precious booty were the remains of the Three Magi, which with great pomp were transported to the Cathedral of Saint Peter in Cologne [Germany]. A magnificent shrine was built to contain the remains of the Magi, and the construction of the new Cathedral began in 1248 to accommodate the thousands of pilgrims.

Now, the patron saint of the city was St. Maurice who was depicted as black. It is possible that due to the influence of the cult of St. Maurice, one of the three Magi began also to be imagined as black.

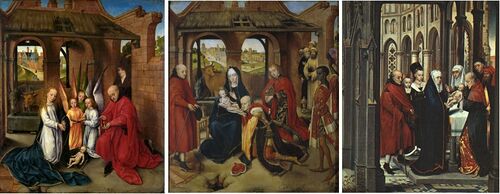

The image moved beyond Cologne and Germany when the artist Hans Memling (c. 1430 –1494), originally from Flanders, chose to copy the renowned Columbia Adoration Altar piece by his former master Jan van Den Weyden (c. 1400 –1464), and made one telling alteration. He painted its third white Magus as black.

In Rogier van der Weyden's Adoration there is no black King.

In the Polyptych of Hulin de Loo (attributed to Hans Memling) the Black King is there.

And so is in Hans Memling's Adoration

And in the Jan Floreins Altarpiece.

Memling’s Adoration iconography was copied by the leading artists of the day and through those copies, the image spread throughout Europe as reproductions by artists of varying skills.

By the end of the 15th century CE, within Europe, the three kings were regarded as representative symbols of Africa, Asia, and Europe, and their depiction within Renaissance and Baroque art frequently included a black king. In the Cologne Tale the Black King was Caspar, but elsewhere he was often rather identified with Balthasar.

Fairly common in Northern European art by the end of the 15th century, the Black King was less frequent in Florentine Renaissance art. Central Italian artists were among the last to adopt the image, though black attendants were sometimes included in the retinue of three white Magi.

IN the meantime, a completely different development occurred in Ethiopia. A 16th cent. Ethiopian book claims that the Magi, the 3 kings who visited Jesus were all Ethiopians. Legend has it that they consumed coffee on their journey to stay awake. In their memory coffee in Ethiopia is today served 3 times. Serving are named after the Magi Abol, Tona & Baraka.

The black Magus challenged the stereotypical European Renaissance concept of a black African in that rather than portrayed as a barbarian, his fashionable, often outlandish, clothes signified him to be civilized.

However, the Black King did not represent an inclusive, positive standard for viewing Blackness. Rather, he served as a metaphor for the spread of Christianity as extending throughout three continents.

In addition to his blackness, he has three distinct attributes to indicate his exoticism to Renaissance viewers: he wears earrings (no white Magus has been found to be wearing one), opulent dress, and is presented as narcissistic, all emphasizing his “otherness” and creating a cultural divide between himself and the white Magi. The divide is further emphasized by him invariably being last in the line.

Only by some artists the "Black King" was portrayed in a fully dignified fashion, or took central stage in the Adoration scene. The most conspicuous examples of this trend are those offered in the 17th century by some Dutch painters such Paul Rubens or Hendrik Heerschop.

In more recent times the idea of the "Black King" has been revived in an inclusive fashion by Gian Carlo Menotti in "Amahl and the Three Night Visitors" (1950) and Duke Ellington in "Three Black Kings (1976)

Exhibits

"Balthazar: A Black African King in Medieval and Renaissance Art", an exhibit curated by Kristen Collins and Bryan Keene at The Getty Center in Los Angeles, CA in 20019-2020. See Virtual tour

- "Early medieval legends reported that one of the three kings who paid homage to the newborn Christ Child in Bethlehem was from Africa. But it would be nearly one thousand years before artists began representing Balthazar, the youngest of the magi, as a Black African. This exhibition explores the juxtaposition of a seemingly positive image with the painful histories of Afro-European contact, particularly the brutal enslavement of African peoples."

Bibliography

Paul H D Kaplan. The Rise of the Black Magus in Western Art. Studies in the fine arts: Iconography, 9. Ann Arbor, MI: UMI Research Press, 1985.

- The black attendant to the white magi -- The sources and early development of the black magus/king in literature -- The iconography of blacks in fourteenth-century Germany and Bohemia -- Images of the black magus/king to ca. 1450 -- The black magus/king ca. 1450-1500.

Geraldine Heng. The Invention of Race in the European Middle Ages. New York, NY - Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2018.

- In The Invention of Race in the European Middle Ages, Geraldine Heng questions the common assumption that the concepts of race and racisms only began in the modern era. Examining Europe's encounters with Jews, Muslims, Africans, Native Americans, Mongols, and the Romani ('Gypsies'), from the 12th through 15th centuries, she shows how racial thinking, racial law, racial practices, and racial phenomena existed in medieval Europe before a recognizable vocabulary of race emerged in the West. Analysing sources in a variety of media, including stories, maps, statuary, illustrations, architectural features, history, saints' lives, religious commentary, laws, political and social institutions, and literature, she argues that religion - so much in play again today - enabled the positing of fundamental differences among humans that created strategic essentialisms to mark off human groups and populations for racialized treatment. Her ground-breaking study also shows how race figured in the emergence of homo europaeus and the identity of Western Europe in this time.--Publisher description.

Cord J. Whitaker. Black metaphors : how modern racism emerged from medieval race-thinking. Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2019.

- "This book's aim is to investigate the relationship between the idea of blackness and the notion of sinfulness in the literature and culture of the English Middle Ages, with influences from continental European texts as well. Though the main target of Black Metaphors is the Middle Ages, the book also asserts the profound implications of the historical nexus of blackness and sinfulness for modern life and culture"--Publisher description.

Erin Kathleen Rowe. Black Saints in Early Modern Global Catholicism. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2020.

- "From the sixteenth to the eighteenth centuries, Spanish and Portuguese monarchs launched global campaigns for territory and trade. This process spurred two efforts that reshaped the world: missions to spread Christianity to the four corners of the globe, and the horrors of the transatlantic slave trade. These efforts joined in unexpected ways to give rise to black saints. Erin Kathleen Rowe presents the untold story of how black saints - and the slaves who venerated them - transformed the early modern church. By exploring race, the Atlantic slave trade, and global Christianity, she provides new ways of thinking about blackness, holiness, and cultural authority. Rowe transforms our understanding of global devotional patterns and their effects on early modern societies by looking at previously unstudied sculptures and paintings of black saints, examining the impact of black lay communities, and analysing controversies unfolding in the church about race, moral potential, enslavement, and salvation."--Publisher description.

External links

Pages in category "Black King (subject)"

The following 23 pages are in this category, out of 23 total.

1

- Adoration of the Magi (1462 Mantegna), art

- Adoration of the Magi (1475 Bosch), art

- Adoration of the Magi (1495 Bosch), art

- Adoration of the Magi (1499 Bosch), art

- Adoration of the Magi (1500 Mantegna), art

- Adoration of the Magi (1504 Dürer), art

- Adoration of the Magi (1511 Kulmbach), art

- Adoration of the Magi (1515 Gossaert), art

- Adoration of the Magi (1519 Beer), art

- Adoration of the Magi (1525 Luini), art

- Adoration of the Magi (1530 Girolamo da Santacroce), art

- Adoration of the Kings (1542 Bassano), art

- Adoration of the Kings (1560 Aartsen), art

- Adoration of the Magi (1619 Velázquez), art

- Adoration of the Magi (1629 Clerck), art

- Adoration of the Magi (1640 Zurbarán), art

- Adoration of the Magi (1650 Biscaino), art

- Adoration of the Magi (1660 Murillo), art

- Adoration of the Magi (1730 Ricci), art

- Adoration of the Magi (1750 Casali), art

- Adoration of the Kings (1753 Tiepolo), art

- Adoração dos Magos (Adoration of the Magi / 1828 Sequeira), art

- Journey of the Magi (1846 Binder), art

Media in category "Black King (subject)"

This category contains only the following file.

- 1951 * Menotti (opera).jpg 251 × 352; 36 KB