User talk:Gabriele Boccaccini

Il Paolo Luterano e la Paul-within-Judaism Perspective.

La critica del "Paolo luterano" sembra essere uno degli elementi principali della nuova ricerca su Paolo tutta tesa - sia pure con prospettive diverse - alla riscoperta della sua ebraicità. Talora la critica è presentata con toni così accesi e radicali da sembrar impedire ogni dialogo, al punto da configurasi - nelle parole di Eric Noffke - quasi come un tentativo di damnatio memoriae (o di cancel culture, come oggi si usa dire) volto a cancellare tutto quanto si è detto e sostenuto nella ricerca storica e teologica su Paolo negli ultimi 500 anni, dalla Riforma in poi. Insomma, o Lutero (e Agostino prima di lui) avevano totalmente ragione nella loro comprensione di Paolo o si erano totalmente sbagliati

In effetti se per Paolo luterano si intende il Paolo nemico e distruttore dell'ebraismo la nuova ricerca contemporanea rappresenta un radicale cambio di rotta e un punto di non ritorno. Ha completamente rigettato l'immagine tradizionale del Paolo convertito e apostata, ricollocando la sua figura come ebreo del I secolo e partecipe del dibattito tra le varie componenti giudaiche del Secondo Tempio e quindi anche al centodell'odierno dialogo ebraico-cristiano. Non potrebbe essere altrimenti: il cristianesimo non esisteva allora ancora come una religione separata dall'ebraismo ma come movimento messianico ed apocalittico all'interno del giudaismo. Paolo - come lui stesso rivendica con forza nei suoi scritti - non fu un apostata: nacque, visse e mori' ebreo. La rivelazione di cui Paolo fece esperienza sulla via di Damasco cambio' radicalmente la sua percezione del giudaismo e la sua collocazione all'interno di esso ma in nessun modo dovrebbe essere definita come una "conversione" e un abbandono della religione di Israele. In questo senso, si', il Paolo ebreo e' in un'opposizione irreconciliabile con il Paolo luterano.

Se si guarda invece ai principi fondamentali che usualmente sono associati al Paolo luterano (sola gratia, sola fides, solus Christus), la situazione si presenta molto piu' complessa e sfumata. In alcun casi si potrà addirittura concludere che alcuni dei principi luterani ne escano finanche rafforzati, pur all'interno di una nuova prospettiva.

Sola gratia

Tra i principi luterani questo e' quello che esce piu' solidamente confermato dalla critica contemporanea. Anzi la grazia emerge sempre piu' nell'opera di storici e teologi contemporanea come il centro stesso della teologia paolina.

Cio' che la ricerca cntemporanea dsul Paolo ebreo contestato a Lutero non e' che la salvezza e' per sola gratia ma che cio' debba essere affermato come caratteristica distintiva del cristianesmi in contrapposizione al giudaismo come religione "legalistica" fondata delle opere. Questo e' cio' che la New Perspective di Stendahl and Sanders ha con forza affermato, sulla scia di critica gia' espresse da studiosi come Claude Montefiore o George F. Moore. Il punto non che la salvezza non e' per sola grazia ma che il giudaismo stesso debba essere considerato una religione fondata sulla grazia. Al principio di ogni opera buona vi e' sempre il dono di Dio che si e' manifestato a tutti gli uomini attraverso l'atto creativo e al popolo ebraico in particolare attraverso l'alleanza sinaitica. La legge naturale e la Torah mosaica sono la riposta degli uomini e elle donne a questi doni. La nuova alleanza in Cristo annunciata da Paolo segue lo stesso schema: e' un dono che esige la risposta umana. La struttura del pensiero paolino e' e rimane ebraica.

A chi e' allora rivolta la polemica paolina? Contro una possibile deriva legalistica del giudaismo quale possiamo vedere nel 4 Ezra (e' una possibile via indicata da Sanders per il quale 4 ezra ndicherebbe una prospettica inconciliabile con quelleo che egli definisce la forma condivisa del giudaismo (common Judaism)basta su princiio del "nomismo dell"alleanza, fondato sulla grazia). La polemica paolina tuttvia senbra avere caratteri generali e non essere limitata solo a contestare una ristretta frangia di radicali

La seconda ipotesi che e' quella preferita da Eric Noffke. e' che Si potrebbe in favore di un giudaismo apocalittico antinomista (Noffke). Il problema e' che non abbiamo porve che

- episogio della conversion di Isate e' spesso citato improprimente come un testo che tratta della salaezza di Isat, mente al centro del testo e' la discussione della modalita' della sua conversione. Mom Co' che egli deve fae per essere slavo ma cio' cheeli deve fare per unrsi al giudaismo.

Per un ebreo del Secondo Tempio - come abbiamo detto - esistono due distinte vie di salvezza che sono entrambe doni della grazia di DIo: il dono ddelll'ordine creativo che esige l'obbedienza alla legge naturale e il dono dell'aleeanza per Israele che comporta l'obbedienza della legge mosaica. Nel giudizio finale tutti gli uomini e le donne saranno giudaicati ma secondo leggi diverse, perche' essi sono stati inclusi dalla grazia divina nella salvezza secondo doni diversi: quindi i gentili saranno giudicati secondo a legge naturale, mentre gli ebrei lo saranno secondo la legge mosaica.

Izate e' un gentle, quindi sara' salvo se vive con giustizia secondo natura, esistono infatti giusti tra le nazioni. Potranno esser pochi ma ci sono. Izate pero' vuole unirsi in modo piu' completo al giudaismo. Per il primo "missionario" che incontra (u giudeo ellenista) e' sufficiente per lui diventare un timorato di Dio. Per essere parte del giudaismo come religione del cosmom non importa circoncidersi e seguire gli obblighi della legge mosaica, e' sufficiente seguirne il significato perche il fine della legge e' lo stesso, vivere secondo natura. E cosi' Izate fa, riinuciand all'idolatria e seguendo gli obblighi dei timorati di Dio, diventandoa tutti gli effetti membro di qulla reliione univrsale che per Filone e' il giudaismo.

Per il secondo "missionario" invece (un fariseo?) questo potra' forse anche eseere suffiente alla salvezza del gentile Izate ma non e' sufficiente alla sua conversione, in quanto non lo rende mebro della religione d'Israele. Occorre la circoncisione e con essa viene l'obbbligo di seguire tutti i comandamendamenti della legge mosaica.

L'episodio non testimonia dell'esistenza di un giudaismo antinomista. Il punto e' che per gli ebrei ellenisti il giudaismo e' la religione del cosmo e quindi al gentile non occorre diventare "ebreo" (proselita) per unirsi ad essa ma basti farlo da timorato di Dio. Per gli altri invece, il giudaismo e' la religione del popolo ebraico e l'unico modo di unirsi ad esso per un gentile e' di diventare ebreo facendosi "proselita". Nessuno dei due gruppi ipotizza un giudaismo antinomista, nessuno mette in discussiono il fatto che quanti per nascita siano ebrei ebreo non dovrebbero essere circonciso e che chi sia circonciso (per nascita o per scelta) non debba obbedire alla legge mosaica.

In Paolo e' presente una polemica accesa verso altri gruppi e movimenti giudaica del suo tempo ma tale polemica in alcun modo vuole condurre ad una prospettiva antinomista. L'affermazione che la salvezza e' per grazia non implica nel giudaismo (e in Paolo) un rigetto delle opere.

«Non si pensi di fondare la santità sulle opere, la santità va fondata sull'essere, giacché non sono le opere che ci santificano, siamo noi che dobbiamo santificare le opere. Per sante che siano le opere, esse non ci santificano assolutamente in quanto opere, ma, nella misura in cui siamo santi e possediamo l'essere». Meister Eckhart

Due conseguenze iportnat nella definizione diel principio d sola gratia. Recupero dell'azione delle opere come risposta alla grazia ricevuta.

non ha nulla a che vedere con quella «grazia a buon mercato» con- tro cui si scagliava Dietrich Bonhoeffer21. come dice John Barclay, il ricevimento di questo dono si deve esprimere necessariamente in gratitudine, obbedienza e cambiamento di vita. Questa grazia è gra- tuita (senza precondizioni) ma non a buon mercato (senza aspettative o obblighi). coloro che l’hanno ricevuta devono rimanere in essa, le loro vite trasformate da nuovi abitudini, nuove disposizioni e nuove pratiche di grazia22.

La posizione di Barclay in fondo non e' che un recupero dell'autentica posizione agostiniana e luterana che non intendeva affatto sminuie il valore delle opere di giustiazia e di carita' verso il prossimo ma solo ricordare cnhe esse bvengono come risposta alla grazia ricevuta.

The good works come forth in response to the grace of God enacted in a Christian life. It is through these works that the proper Christian response to justification can be seen--in true love for one's neighbor, this action not being motivated by self-gain but through the example of Christ. It is this expression of the outward nature, the 'outer man," which must be mastered and directed in daily intercourse with the rest of human society. This is done through the joyful acceptance by the inner nature of the grace of Christ in which 'it is his [the Christian's] one occupation to serve God joyfully and without thought of gain, in love that is not constrained' (p. 17).

A Treatise on Good Works by Dr. Martin Luther, 1520

9 Lutero. Libertà del cristiano 1520

XXIII sezione:

“Buone, pie opere non fanno mai un uomo buono e pio; ma un buono, pio uomo fa buone, pie opere” (p. 54) “Come ora gli alberi devono essere prima dei frutti e i frutti non fanno gli alberi né buoni né cattivi, ma gli alberi fanno i frutti; così l’uomo dev’essere già pio o malvagio nella sua persona prima di fare buone o cattive opere; e le sue opere non lo rendono buono o malvagio, ma lui fa buone o cattive le opera” (p. 54)

Sola fides

E' questo il principio piu' fortemente criticato della teologia luterana, se lo si intende nel senso che ad essere salvati saranno solo coloro che hanno esplicita fede in Cristo (accettando la sua signoria e ricevendo il battesimo). Paolo viene comunemente esaltato come il campione dell'universalismo cristiano, come colui che avrebbe allargato i confini della salvezza al di fuori degli "angusti" confini del popolo ebraico. Il tutto in contrapposizione assoluto con il Paolo pre-cristiano , cosi' intollerante nella sua difesa del particolarismo giudaico da perseguitare come eretici i seguaci di Gesu'. Il concetto di "giustificazione per fede" rigidamnte inteso pero' ci pone di fronte al paradosso di un Paolo che in seguito al suo incontro con il Cristo diventa ancora piu' intollerante, affermando che la salvezza una volta prerogativa di color che obbediscono la lla legge antuale e degli che obbediscana ma e' ora drammaticamnte e di colpo ristretta ai soli battezzati (allora - infiniamente piu' dche oggi - un numero limitissimo di persone, ebree e gentili)

Ora non vi dubbio che Paolo abbia annunciato la giustificazione per fede come via di salvezza anzi come via primaria di salvezza, ma rimane per me incomprensibile cme teologi cristiani possano ripetere che "la giustificazione per fede" e' per Paolo l'unica ed esclusiva via di salvezza, senza alcun distinguo e senza provare almeno un senso di brivido per le implicazioni di intolleranza che tale idea ha prodotto e ancor oggi produce).

L'esigenza di superare il paradosso di un Paolo universalista e al tempo stesso campione dell'intolleranza religiosa ha portato a vari tentativi di ridefinire il concetto di giustificazione per fede.

Non per fede in Cristo ma per la fedelta' del Cristo

Alcuni hanno negato che per Paolo la fede in Cristo rappresenti un elemento centrale, che la giustificazione/salvezza non sia per fede in Cristo ma in virtu' della fedelta' del Cristo. Il problema e' che la sostituzione

Non fede in Cristo ma per la defeldta' del Cristo.

G. HEBERT, "Faithfulness and Faith", Theology 58 (1955) 373-379.

L’articolo di Hebert fu severamente criticato da James Barr nel suo celebre libro sulla "Semantica del linguaggio biblico" Articolo di Alber Vanoye] Il valore di un termine non e' dato dell'etimologia ma dal contesto.

<<"Sapendo che l’uomo non è giustificato in virtù di opere di Legge, ma per mezzo della fedeltà di Cristo, anche noi abbiamo creduto in Cristo, per essere giustificati in virtù della fedeltà di Cristo e non in virtù di opere di Legge (Gal 2:16)>>

Giustificazione per fede in Paolo

Un esame delle lettere paoline ci offre un quadro coerente Le lettere paoline ' chiarissimo in Paolo che la giustificazione e' un

(1) e' un dono di grazia di Dio "in virtu' della rdenzione realizzata dal Cristo Gesu (rom 3:

Gal Gesu' Cristo ... ha dato se stesso per i nostri peccai, per stapparci da questo mondo perverso, secondo la volonta' di Dio e Padre nostro" (Gal 1:4) Egli "e/' stat[ messo a morte per i nostri peccati ed e; stato resuscitato per la nostra giustificazione" (Rom 4:25)

"But you were washed, you were sanctified, you were justified in the name of the Lord Jesus Christ and by the Spirit of our God. (1Cor 6:11)

(2) avviene solo per fede, indipendentemente dalla legge.

"L'uomo non e' giustificato dalle opere della legge ma soltanto per mezzo della fede in Gesu' Cristo (Gal 2:15) ... Se la giustificazione viene dalla legge, Cristo e' morto invano" (Gal 2:21).

"Che nessuno possa giustificarsi davanti a Dio per la legge risulta dal fatto che il giusto vivra' in virtu' della fede" (Gal 3:11) "Ora a legge non si basa sulla fede, al contrario dice che chi partichera' queste cose, vivra' per esse" (Gal 3:12) Ne consegue che chi obbedisce e' salvo ma chi trasgredisce e' sotto la maledizione. Invece Cristo riscatta il peccatore dalla maledizione (gal 3:13

"L'uomo e; giustificato per fede indipendentemente dalle opere della legge" (Rom 3:28)

<<La legge da' solo la conoscenza del peccato "La legge provoca l'ira" (Rom 4) - "La legge giunse a dare piena coscienza della caduta" (Rom 5:20)

(4) E' offerto sia a ebrei che a gentili ed e' stata promessa dalla Scitture. Lesempio di Abramo" ebbe fede e questo gli fu accreditato come giustizia.

"Am me era stato affidato l vagelo per i non circoncisi come a Pietro quello per i circoncisi" (Gal 2:7)

In Cristo Gesu' non e' la circoncisione che conta o la non circoncisione, ma la fede che opera per mezzo della carita' (Gal 5:6)

"Questa beatitudine riguarda chi e' circonciso o anche chi non e' circonciso?

"se ebrei come Pietro e Paolo cercavano la giustificazione in cristo, allora anche loro dovevano averne bisogno» (Westerholm, 15)

Ministero dei

Paolo afferma che la giusticazione per fede e' annunciata', "promessa dalle scritture"

La giustificazione e' promessa dalla legge ad Abramo e il dono della legge nn annulla la promessa (Gal 3). A questo riguardo la legge fu come un pedagogo che ci ha condotto a Cristo (Gal 3

==

DI solito queto viene presentato in alternativa o sostituzione della legge, che avrebbe carattere solo temporaneo

Vi sono tuttavia degli elementi contraddittori:

Paolo

Ma per Paolo non e' cosi'

"La legge dunque e' contro le promesse di Dio? Impossibile! (Gal 3:21)

"Tgliamo dunque ogni valore alla legge mediante la Fede? Niente affatto, anz cofermiamo la legge" (Rom 3:31)

CHe diremo dunque, che la legge e' peccato? No certamente" (Rom 7:7)

E curiosamente ogni volta ch parla del giudizio finale lo fa in termini

Paolo ripete l’indiscus- sa convinzione del Secondo tempio che nel giorno del giudizio, Dio «renderà a ciascuno secondo le sue opere» (Rom. 2,6 et passim). Mai Paolo mette in dubbio che la salvezza attende quegli ebrei e gentili i quali compiano “opere buone” (seguendo rispettivamente la torah e la loro coscienza). i peccatori saranno puniti e i giusti saranno salvati senza alcuna parzialità. «tribolazione e angoscia su ogni uomo che opera il male, sul giudeo, prima, come sul greco; gloria invece, onore e pace per chi opera il bene, per il giudeo, prima, come per il greco. Dio infatti non fa preferenza di persona» (Rom. 2,9-11). È la stessa idea che Paolo aveva ribadito anche in ii corinzi e che avrebbe ripetuto di nuovo alla fine della lettera ai Romani: «tutti in- fatti dobbiamo comparire davanti al tribunale di cristo, per ricevere ciascuno la ricompensa delle opere compiute quando era nel corpo, sia in bene che in male» (ii cor. 5,10). «tutti infatti ci presenteremo 10 G. Boccaccini, The Pre-Existence of the Torah. A Commonplace in Second Temple Judaism, or a Later Rabbinic Development?, “Henoch” 17 (1995), pp. 329-350. 11 G. Boccaccini, Hellenistic Judaism. Myth or Reality?, in a. norich, y.z. eliaV (a cura di), Jewish Literatures and Cultures. Context and Intertext, Brown Ju- daic Studies, Providence 2008, pp. 55-76. 153 al tribunale di Dio [...] ciascuno di noi renderà conto di se stesso a Dio» (Rom. 14,10-12). in nessun passo nelle sue lettere Paolo attesta una comprensione del giudizio finale diversa da questa.

Giusficazione per fede o salvezza per fede?

Dunque, riassumendo: La giustificazione per fede e' via di salvezza, e' conseguenza del sacrificio del Cristo, avviene solo per sola fides, indipendentemente dalla legge ed e' un dono offerto sia a ebrei che a gentili secondo la promessa delle Scritture. AL tempo stesso Paolo ci dice la promessa non toglie valore alla legge e il giudizio rimane fondato sulle opere.

Come e' possibile tenere insieme questi elementi apparentemente contradditori?

Il nodo e' rappresentato dal rapporto tra giustificazione e salvezza. Siamo proprio sicuri che "giustificazione per fede" equivale a "salvezza per fede"?

Un libro fondamentale di Chris VanLandingham pubblicato nel 2006, "Judgment & Justification in Early Judaism and the apostle Paul" ha affontato il problema nel contesto del giudaismo del I secolo raggiungendo una conclusioni importante: i due concetti di giustificazione e salvezza sono strettamente connessi ma non perfettamente sovrapponibili.

Già Sanders (con Karl Donfried) aveva notato che, nelle parole di Paolo, la giustificazione è coniugata al passato, mentre la salvezza lo è al futuro: le persone «sono state giustificate» per fede, ma «saranno salvate» (o dannate) in un giudizio in cui «Dio [...] renderà a ciascuno secondo le opere» (Rom. 2,6) (Rom. 5,9-10; 13,11; i tess. 5,8; i cor. 1,18)18. Dal punto di vista dei membri battezzati del movimen- to di gesù, la giustificazione per fede appartiene al passato, mentre la salvezza nel giudizio finale di ciascuno appartiene al futuro. Ma Sanders intendeva questo linguaggio come evidenza di un processo universale attraverso il quale tutti gli esseri umani (ebrei e gentili al- lo stesso modo) vengono salvati per grazia (poiché inclusi nel nuovo patto in cristo) e la loro salvezza sarà confermata nel giudizio fina- le dalle buone opere attraverso le quali hanno dimostrato la loro vo- lontà di «rimanere» nel patto: «l’idea fondamentale di Paolo sembra essere così che i cristiani sono stati purificati e stabiliti nella fede, e debbono rimanere tali, per essere trovati irreprensibili nel giorno del Signore [...] Paolo è consapevole che non tutti rimangono saldamen- te nella condizione di purificazione»19.

il problema con questa interpretazione, come osservato da chris Vanlandingham, è che identifica la giustificazione per fede «al ver- detto di assoluzione che un credente riceverà nel giudizio finale». al contrario, la giustificazione per fede «descrive ciò che accade all’i- nizio della propria esistenza cristiana, non alla fine [...] Descrive la persona perdonata dei suoi peccati e liberata dal dominio del pecca- to»20.

<<ovviamente, per i peccatori, la giustificazione mediante la fede è una via per la salvezza; secondo Paolo, «il vangelo [...] è potenza di Dio per la salvezza di chiunque crede, del giudeo, prima, come del greco» (Rom. 1,16). la giustificazione per fede, tuttavia, non è la salvezza per fede. ciò che Paolo ha in mente non è il destino di tutta l’umanità, ma il destino dei peccatori. Per Paolo, come per tutti i primi seguaci di gesù, ciò che è già stato ricevuto tramite il battesi- mo è il perdono dei peccati passati per i peccatori che si sono pentiti e hanno accettato l’autorità del Figlio dell’uomo.>>

Quando Paolo parla di giustificazione per fede, parla dunque di qualcosa di diverso dal giudizio finale secondo le opere di ciascuno. la giu- stificazione per fede è un dono incondizionato di perdono offerto ai peccatori pentiti che hanno fede in gesù. la salvezza è il risultato del giudizio finale in cui tutti gli esseri umani saranno giudicati in base alle proprie opere. chris Vanlandingham era stato del tutto corretto nelle conclusioni del suo studio sul giudizio e la giustificazione nel giudaismo del Secondo tempio e nell’apostolo Paolo:

- una persona che è stata «giustificata» è una persona che è stata per- donata dei peccati passati (che quindi non costituiscono più un pro- blema), purificata dalla colpa e dall’impurità del peccato, liberata dalla propensione umana al peccato e quindi dotata della capacità di obbedire. il giudizio finale determinerà quindi se tale persona, come atto di volontà, ha seguito questi benefici ottenuti attraverso la mor- te di cristo. Se è così, la vita eterna sarà la ricompensa; altrimenti, la dannazione24. (VamLandigham, 335)

Con giustificazione Paolo intende prima di tutto il perdono dei peccati.

In effetti se al termine giustificazione per fede si sostituisca quello di "perdono per fede" i testi paolini mantengono inalterata tutta la loro coerenza, anzi Paolo puo' affermare che il perdono per fede rappresenta una nuova via di salvezza nel momento in cui al tempo stesso riafferma che il giudizio finale avverrà attraverso un giudizio delle opere.

EPaolo si ritrova collocato all;interno del pensiero del primo cristianesimo

Non solo ma scompare il paradosso che del "rivoluzionario" concetto paolino di "salvezza per fede" non esista alcuna traccia fino alla sua "riscoperta" operata da Agostino (su cui Lutero fonda la sua interpretazione). Della salvezza per fede non c'e' traccia nei sinottici e nemmeno nella tradizione paolina. Scompare anche il paradosso della "censura" che gia' gli Atti avrebbero operato del pensiero paolino.

In Matthew il riferimento al sangue di Cristo: This is my blood of the covenant, which is poured out for many for the forgiveness of sins.

gli Atti sono il linea con questo

"Peter replied, “Repent and be baptized, every one of you, in the name of Jesus Christ for the forgiveness of your sins. And you will receive the gift of the Holy Spirit." (Atti 2:38)

"Tutt i profet All the prophets testify about him that everyone who believes in him receives forgiveness of sins through his name. (Atti 10:43)

Anche le Deauteropaoline sono sulla stessa line, ponendo al centro il perdono di DIo

"In Gesu' abbiamo la redenzione mediante il suo sangue, la remissone dei peccati secondo la ricchezza della sua grazia" (Efesini 1:7) "Con lui Dio ... a perdonato tutti i peccati, annullando il documento scritto del nostro debito, le cui condizioni ci erano sfavorevoli" (Col 2:13-14). "Il Signore vi ha perdonato" (COl 3:13)

1 John 1:9: " If we confess our sins, he is faithful and just and will forgive us our sins and purify us from all unrighteousness.

In sintesi, la teologia cristiana ha arbitrariamente equiparato giustificazione e salvezza, separando Paolo non solo dal sua contesto giudaico, ma anche dal contesto del primo cristianesimo per cui giustificare equivale non a salvezza maagli effetti del perdono di Dio.

"Sapendo che l’uomo non è perdonato (giustificato) in virtù di opere di Legge, ma per mezzo della fedeltà di Cristo, anche noi abbiamo creduto in Cristo, per essere perdonati (giustificati) in virtù della fede in Cristo e non in virtù di opere di Legge

La dimensione apocalitica del pensiero paolino

Il testo di VanLandingham e' un testo fondamentale. Egli correttamente coglie che la giustificazione non e' solo "perdono, purificazione e purificazione dei peccati passati" ma anche un’emancipazione dal dominio del peccato sull’umanità»31 (VanLindingham, 245) ottenuti mediante la fede in cristo. Cio' L'autore non coglie in tutta la sua ampiezza e' la dimensione apocalittica del pensiero paolino , la sua enfasi sul potere del peccato,

Cosi' si dira' nella lettera agli Efesini: "La nostra battaglia non è contro creature fatte di sangue e di carne, ma contro i Principati e le Potestà, contro i dominatori di questo mondo di tenebra, contro gli spiriti del male che abitano nelle regioni celesti." (Efesini 6,12)

Qual e' dunque il problema di Paolo

Il problema non e' la legge, il problema e' "il peccato [che] prendendo occasione dal comandament mi ha sedotto e per mezzo di esso mi ha dato la morte. La legge e' santa e santo e giusto e buono e il comandamento" (Rom 7). Non e' la legge ad essere respnsabile ma il peccato: "esso per rivelarsi peccato mi ha dato la morte servendosi di cio che e" bene" (Rom 7:13)

C'e' in me un;altra legge che spinge l'uomo al male.

Questo e' il linea con la profezia di Enoc

E' quanto dice nelle sue lettere ed e' come lo interpreta gli atti degli apostoli, e come i sinottici presentano il valore della fede.

In questo modo e' possibile riaffermare - come diceva Lutero - che la giustificazione (il perdono) e' per sola fede per sola esplicita fede in Cristo, anche se la fede puo' non essere esclusivisamnte determinante

Gesu' non ci ha liberati dalla legge mosaica, ma da questa altra legge, "dalla legge del peccato e della morete" (8:

cosa che era impossibile per la legge mosaica, perche' la carne la rendeva impotente"

Gesu' e' moto per i peaccatori, per molti non per tutti. (Rom 5:6-11)

"Cristo mori' per gli empi nel tempo stabilito.

Solus Christus

E' Cristo l'unica via di salvezza? Alcuni esponenti della "Paul-within-Judaism Perspective", come John Gager o Mark Nanos hanno suggerito chele lettere di Paolo sono rivolte ai gentili e che e' a solo che a loro che Cristo e' presentato come via di Salvezza. Mentre il dono della torah e' riservato agli ebrei circoncisi, il dono della nuova alleanza e' rivolto esclusivamente ai gentili. Per loro esclusivamente la salvezza e' in Cristo.

<Altri hanno cercato di limitare l'annuncio della giustificazone fede, come esclusivo annunzcio dal salvezaa per i gentili (e non per gli ebrei). E' il fondamento dellidea delle Due vie di salvezza" la quale gode di una certa favore in ambito ebraico cristiano per la sua capacita' di disinnescare alla radice l;idea della "missione" cristiana verso Israele. Ma spostare l'intolleranza paolina dagli ebrei ai gentili non e' poi un grande passo in avanti. Gli ebrei hanno la Torah, ma Cosa ne e' dei gentile che non credono in Cristo?

L'idea di due autonome vie di salvezza e' stata molto criticata. ANzitutto dal punto di vista dell'esegesi dei testi paolini in quanto affermarla richiede tortuose esegesi dei testi e l'assunto che Paolo faccia un un'uso della retorica ai limiti dello spregiudicato per dire in realta' il contrario di quello che dice. Vi e' poi l'aspetto teologico in quanto priva il messaggio cristiano del suo centro esclusivo,

La stessa critica e' stata da alcuni a me riservata per la mia proposta delle "tre" vie di salvezza, senza considerare che la mia era una descrizione storica, non teologica. Per un ebreo del Secondo tempio -- abbiamo visto esistono "due" vie di salvezza: la legge naturale per i gentili e la legge mosaica per gli ebrei. Ad esse (dal punto di vista prettamente storico) Paolo ne "aggiunge" una terza: la "giustificazione per fede". La logica di Paolo e' la stessa per la quale al dono della legge naturale Dio ha aggiunto il dono dell'alleanza sinaitica, ovvero a causa delle trasgressioni <cit>. Paolo infatti e' un ebreo apocalittico e al centro del suo pensiero e' una coscienza fortissima del potere del male, assieme ad una coscienza fortissima della misericordia e della grazia di Dio (elemento questo :luterano") che lo spinge a vedere Dio imegnato alla ricerca di un rimedio per lo stato di peccato nel quale si trova l'umania' sotto il dominio di Satana che e' il dio di ques mondo"

La buona creazione, dono di salvezza di Dio a tutta l'umanita', e' stata corrotta dal peccato per cui la maggioranza delle persone sono cadute preda delle loro passioni (rom

Per questo, per limitare il diffondersi del male si e' reso nesesario un ulteriore dono, quell del Patto mosaico, riservato al popolo di Israele con il suggello della circoncisione. Ma il fine dlla Toah e' limitato dal suo offrie un argine non un rimedio definitito ad offrire la conoscenza i cio' che e' bene e di cio' che e' male. La Torah non ha il potere di porre l'uomo al riparo dal potere del male ma di rivelarne l'esistenza. AL tempo stesso la Torah e' la profezia di un dono ancora piu' grande (independetemente dalla Legge) che e' quello che lui annuncia con il sacrifico e la morte del Cristo.

Cristo e' il secondo Adamo la cui axione viene a cntrobilanciare il potere del male.

Il problema e' come questo dono si rapporta ai doni precedenti. E' indubbio che per Paolo Cristo ha una centralita' assoluta e un ruolo definitivo.

La "giustificazione per fede" e'la via maestra, tanto che egli considera il suo miniterso piu' grande di quello di Mose' che annunciava la condanna, mentre Paolo annuncia la salvezza.

Mail dono della grazia annulla i precedenti doni di Dio. Si aggiunge ad essi? o si sostituisce ad essi? Cosa ne e' della legge naturale e della legge mosaica dopo l avenuta del Cristo?

La teologia cristiana ha avuto una sguardo benevolente sulla legge naturale. Dante La chiesa cattolica Il cncilio Vati Cristo in fonso e' colui per il quel

Tale sguardo benevolente invece e' sempre stato negato alla legge mosaica. La ragione ' che lgi il ifiuto degli "ebrei" e' unteso come il iuto di coloro che pur conoscendo la verit's, rimamono d essi ostinatamente contrari.

Cristo cosi' e' la fine (non il fine) della legge.

Il fatto e' derivato dalle polemica che hanno accompagnato l'emergere del cistianesimo cme religione autonoma e separata dll'ebraismo e quindi da secoli di diffcile convivenza tra le due religioni sorelle. Ai gentili non cristiano veniva lasciato la presunzione di innnocenza la cui "ignoranza" si perdonava (e si perdona) attribuendola a buona fede . Gl ebrei invece erano colpevoli perche' pur "sapendo" rifiutano coscientemente la grazia divina. Quindi al contrario

Epuure Paolo non parla dell'allenza con Israele e della Legge mosaica al passato ma al presente. Le alleane di Dio sono irrevocabili>La legge e' buona e santa.

Pao dunque immagina una scenario in cui ilCristo e' l'unica

Una cosa e' dire che la salvezza e "in Cristo" e un'altra e' dire he la salvzzaa e' limitata "alla fede in Cristo" (e quindi al battesimo o cumunque all'esplicito riconoscimento della signoria del Cristo). Allo stesso mod con cui iuna cosa e' fire che la salvezza e' "per legge" o che e' solo per la circoncisione.

Per Paolo non is tratta di vie escluvise, perché I doni non si annullano ma si integrano nel piano di Dio. Non vi tratta pero’ neppure di vie autonome e separate perché tutto è da Paolo ricondotto al Cristo, principio e fine di ogni cosa.

Dal punto di vista di Paolo, la salvezza e’ sempre e comunque “in Cristo.”, il quale per Paolo Cristo e’ colui “nel quale e per il quale tutte le cose sono state create e

Come tale il Cristo è il fondamento della legge naturale, è la sapienza rivelata agli uomini al momento della creazione.

Cristo è anche il fine della legge mosaica, che di lui è profezia e buon pedagogo cui Dio ha affidato con fiducia i figli del suo popolo Israele.

Quindi la salvezza “in Cristo” include non solo i “giustificati per fede” ma anche coloro che tra le nazioni sono giusti secondo la legge naturale e coloro che tra gli Israeliti sono giusti secondo la legge mosaica. Anch’essi ricevono salvezza in Cristo pur non conoscendolo o essendone consapevoli. Cristo e’ preesistente, e’ colui attraverso il quale tutto e’ stato e alla fine dei tempi sara’ il Giudice di fronte al quale tutti, ebrei e gentili, saranno giudicati ciascuno secondo le proprie opere. Quindi il gentile che osserva la legge naturale senza saperlo osserva la legge del Cristo, che e’ il fondamento dell’rdine creative. El’breo che osserva la torah, osserva la legge che fu data ai figli come buon pedagogo perche’ annunciasse loro la venuta del Cristo e ricevera’ per questo salvezza dal Cristo. Solo ai peccatori la fede esplicita in Cristo e’ richiesta coscientemente come condizione per ricevere il battesimo e la giustificazione 9il perdono dei peccati), ma la salvezza per tutti avviene in Cristo anche per i gentili che siano giusti second la legge naturale e per gli ebrei che siano giusti seconod la Legge mosaica. In fondo la posizione di Paolo non e’ lontana da quella espressa dal Vangelo di Matteo ai giusti nel giudizio finale. Ad esssi non e’ chiesta la loro fede ma e’ detto: “tutte le volte che avete fatto al piu’ piccolo dei miei fratelli lo avete fatto a me

Per Paolo dunque è sempre il Cristo (non la fede in lui) il mediatore della salvezza, le tre vie di salvezza sono tutte a lui riconnesse e integrate a di fuori di ogni prospettiva abrogativa o sostitutiva. L’ulivo santo di Israele nasce dal terreno dell’umanità e I giustificati per fede vi sono innestati, e alla fine tutto Israele sarà salvato. Perché le promesse di Dio sono irrevocabili.

Il giudaismo rabbinico opererà la stessa integrazione tra le proprie due (originariamente autonome) vie di salvezza, sviluppando il concetto di preesistenza della Torah, per cui l’ordine creativo è anch’esso inglobato nella Torah come legge noachica.

La Torah la quale comprende sia l’alleanza noachica con l’intero genere umano, sia l’alleanza sinaitica con il popolo d’Israele per quale riceveranno salvezza sia I Giusti di Israele e tra le nazioni. Nell’ottica della teologia rabbinica è possibile dunque ora affermare che la Torah è l’unica ed inclusiva via di salvezza. Anche i gentili che compiono opere di giustizia dunque seguono, senza esserne coscienti, la Torah.

Paolo – come abbiamo visto - offre una prospettiva diversa ma analoga, in cui i doni di Dio (inclusa l’alleanza sinaitica) non sono abrogati ma integrati “in Cristo”. Perché mai del resto un dono più grande dovrebbe annullare i doni precedenti? Per Paolo la giustificazione per fede è la via maestra per i peccatori ma non è l’unica ed esclusiva via di salvezza. Per Paolo il Cristo è l’unica ed inclusiva via di salvezza.

Poalo apocalittico

una grazia piu' grande che non solo giustifichi l'uomo peccatore ma lo renda capare di rispondere al dono ricevuto con frutti di giustizia.

Grace vs. evil, not grace vs. law

A collective act of grace (the end of time) vs. an individual act of grace for the sinners.

@2015 Gabriele Boccaccini <work in progress>

Le tre vie di salvezza di Paolo l'ebreo Una rilettura della Lettera ai Romani all'interno del giudaismo del Secondo Tempio. Gabriele Boccaccini, Università del Michigan

(1) Introduzione: Un nuovo paradigma nello studio di Paul

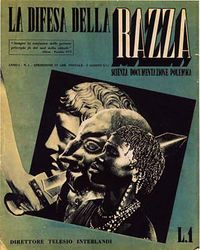

Nel contesto del giudaismo del primo secolo la figura di Paolo appare tra le più enigmatiche e una di quelle di più difficile collocazione. Un alone di mistero, se non la maledizione di un antico tabù, sembra ancora aleggiargli attorno e rendere difficile una comprensione serena della sua esperienza. Su Paolo pesa la reputazione ingombrante di primo grande teologo sistematico cristiano ma anche il sospetto – se non l’accusa – di avere contribuito in modo decisivo alla separazione tra cristianesimo ed ebraismo e di avere gettate le basi di una velenosa polemica contro la Torah e il popolo di Israele, foriera di pregiudizi e discriminazioni, fino alla tragedia dell’Olocausto.

La riscoperta dell’ebraicità di Gesù, che dalla fine dell'Ottocento vede impegnati in uno sforzo comune studiosi ebrei e cristiani, ha a lungo contribuito a scavare ulteriormente il solco. Più la figura del Maestro si rivelava compatibile con lo spirito del giudaismo del suo tempo, più il suo discepolo più famoso appariva l’uomo della rottura, quando non addirittura l’autentico fondatore del cristianesimo come religione distinta dall’ebraismo

Per secoli, del resto, i cristiani hanno lodato, e gli ebrei hanno accusato, Paolo di aver separato il cristianesimo dal giudaismo. Ai cristiani Paolo è apparso come il convertito capace di smascherare e denunciare la "debolezza" (se non la malvagità) del giudaismo, e agli ebrei come il traditore che ha trasformato la fede dei suoi antenati in una caricatura (Zetterholm 2009). Paolo e' divenuto così al tempo stesso l'avvocato dell'universalismo cristiano e il principale sostenitore della esclusività cristiana: tutti, ebrei e gentili, uomini e donne, liberi e schiavi, sono chiamati e accolti alla fede, ma per tutti c'è unica via di salvezza, in Cristo, creando cosi' un muro di intolleranza tra credenti e non-credenti. Condannato dalla propria "perfidia", dalla propria colpevole assenza di fede, il popolo ebreo, una volta "eletto", si trova ora privato di ogni dignita', rigettato al pari dei gentili alla dannazione se non attraverso l'esperienza individuale della conversione.

Eppure in questo quadro ci sono molti conti che non tornano. Tra gli autori del primo cristianesimo Paolo è quello che con maggior forza rivendica la propria ebraicità («Anch’io sono Israelita, della discendenza di Abramo, della tribù di Beniamino» – Rom 11,1) difende l'irrevocabilita' delle promesse divine ("Dio ha rigettato il suo popolo? Niente affatto!", Rom 11:1) e con più prontezza ribadisce i “privilegi” di Israele di fronte allo zelo dei nuovi convertiti tra i gentili («Tu, oleastro [...] non menar vanto contro i rami!» – Rom 11,17-18).

Con Krister Stendhal, E.P. Sanders, James D.G. Dunn e la “New Perspective” si è cominciato fin dagli anni ’70 a mettere in discussione quella opposizione radicale tra grazia e legge che faceva di Paolo il critico implacabile del “legalismo” ebraico, riconoscendo in tale opposizione non la voce autentica del primo secolo, ma il riflesso anacronistico della polemica che nel sedicesimo secolo divise il cristianesimo con la Riforma7. Con il crollo del “Paolo luterano” è caduto anche il mito della supposta inossidabile coerenza teologica del pensiero paolino. Si e' cosi' cominciato a insistere piuttosto sulla paradossalità della teologia paolina, sulla sua non-sistematicità, sul suo essere legata a problemi e situazioni contingenti, e quindi sulla sua sostanziale incoerenza. Paolo non era un teologo o un pensatore sistematico. Paolo era un pastore, che aveva a che fare con comunità di persone in carne e ossa e con problemi estremamente concreti. In Paolo – come affermato con efficace sinteticità da E. P. Sanders – la soluzione precede il problema. Egli vedeva i gentili avvicinarsi con fede ed entusiasmo al cristianesimo; il suo sforzo teologico fu nel cercare di giustificare a posteriori il fatto avvenuto. La riflessione paolina non sarebbe allora la premessa teoretica all’ingresso dei gentili nella comunità cristiana, ma il tentativo, finanche un po’ confuso e teologicamente non del tutto coerente, di giustificare l’evento nel quale si riconosceva l’azione misericordiosa di Dio.

La nuova prospettiva ha cercato difficile sbarazzarsi degli aspetti più sprezzanti della lettura tradizionale (luterana) di Paul (sostenendo che l'ebraismo anche deve essere considerato come una religione "rispettabile" in quanto anch'esso basato sulla grazia) Ha efficacemente riscoperto la struttura giudaica del pensiero di Paolo, sottolineandone gli aspetti pragmatici e pastorali rispetto alla sua presunta inossidabilita' teologica. E tuttavia non ha messo in discussione la visione di Paul come il critico del giudaismo e l'avvocato di un nuovo modello sostituivo di relazioni tra Dio e l'umanità che sostituisce l'antica alleanza: la grazia di Dio "in Cristo" supera l'alleanza ebraica sia per gli ebrei e gentili, con la creazione di un terzo "popolo".

<Prima di concludere che Paolo fu incoerente occorre tuttavia domandarsi se tale oggi egli ci pare semplicemente perche;' non riusciamo a capire il contesto e la coerenza originaria del suo pensiero >

Sulla scia di queste considerazioni gli autori della New Radical Perspective on Paul" si sono spinti ben oltre, sono giunti a ribaltare clamorosamente il quadro tradizionale, affermando l’immagine di un Paolo fedele alla Legge e cosciente promotore di una “doppia strada” alla salvezza in cui la fede in Gesù è offerta come via di salvezza ai non-ebrei, senza annullare (anzi ribadendo) la funzione salvifica della Torah per gli ebrei. Nell’affermare il primato della grazia nelle sue lettere Paolo si sarebbe sempre e solo rivolto ai pagani indicando a loro esclusivamente il Cristo come via di salvezza. La “conversione” di Paolo non sarebbe altro che una chiamata a predicare ai gentili, che lascia inalterato, anzi rafforza il patto di alleanza tra Dio e Israele. L’entusiasmo revisionista è arrivato al punto di affermare trionfalmente – come già si era fatto con Gesù – che contrariamente a quanto finora da tutti ritenuto «Paolo non era cristiano»9.

La soluzione è teologicamente attraente e si salda armoniosamente agli sforzi del dialogo ebraico-cristiano contemporaneo. Non a caso molti dei propugnatori della Radical New Perspective sono teologi militanti, piuttosto che specialisti del giudaismo del Secondo Tempio. Ma si tratta di una ipotesi storicamente plausibile o di una anacronistica rilettura post-Olocausto del maestro di Tarso?

<< Un nuovo paradigma sta oggi emergendo con la Radical New Perspective - un paradigma che mira a riscoprire pienamente l'ebraicità di Paolo. Paradossalmente, "Paul non era un cristiano" (Eisenbaum 2009) da quando il cristianesimo al tempo di Paolo è stato altro che un movimento messianico ebreo, e quindi Paul dovrebbe essere considerato altro che un Secondo Tempio Ebreo. Che altro avrebbe dovuto essere? Paul è nato ebreo, di genitori ebrei, venne circonciso e nulla nei suoi supporti di lavoro (o addirittura suggerisce) l'idea che è diventato (o si considerava) un apostata (Boccaccini 1991). Al contrario, Paolo è stato il membro del movimento di Gesù e con forza e chiarezza inequivocabile orgogliosamente rivendicato la sua ebraicità e ha dichiarato che anche Dio non ha respinto l'alleanza di Dio con il popolo eletto: "Dio ha rigettato il suo popolo? Niente affatto! Io stesso sono Israelita, un discendente di Abramo, un membro della tribù di Beniamino (Romani 11: 1; cfr Fil 3: 5). >>

E' facile di fronte in questo modo rimanere sconcertati da una prospettiva che sembra forzare la teologia paolina su binari ed interpretare come "retorico" o irrilevante tutto cio' che non rientra in questo schema. E così' può' tornar comodo tornare all'alveo di partenza, all'immagine tradizionale sia pure edulcorata dall'ammissione che si' Paolo era e si sentiva ebreo ma che una volta eliminati gli aspetti più' chiaramente caricaturali e dispregiativi "l'esegesi paolina di Lutero non e' stata cosi lontana dal Paolo autentico, come la recente ricerca ha voluto dimostrare" (Pulcinelli, p.321).

Di fronte alle Basta quindi provare le incongruenze della nuova prospettiva su Paolo per ritornare al Paolo della tradizione o c'e' una strada diversa per recuperare l'ebraicita' di Paolo all'interno della complessita' del giudaismo del Secondo Tempio. E' quanto ci proponiamo di esplorare in questo saggio.

Basta quindi provare le incongruenze della nuova prospettiva su Paolo per ritornare al Paolo della tradizione o c'e' una strada diversa per recuperare l'ebraicita' di Paolo all'interno della complessita' del giudaismo del Secondo Tempio. L'opposizione tra il Paolo cristiano e il Paolo ebreo e' dunque quella tra chi vede in Paolo un'unica via di salvezza in Cristo e coloro che propugnano due vie di salvezza, oppure c'e' una prospettiva diversa piu' storicamente plausibile nel quale collocare Paolo l'ebreo. E' quanto ci proponiamo di esplorare in questo saggio: non una interpretazione esaustiva della figura dell'apostolo, ma una riflessione sulla sua ebraicita' nel contesto giudaico del suo tempo.

(2) Il giudaismo al tempo di Paolo

Se oggi possiamo parlare del Paolo ebreo e' perche' la nostra comprensione dell’ebraismo del primo secolo è in questi ultimi decenni profondamente cambiata. I manoscritti del Mar Morto e i cosiddetti apocrifi e pseudepigrafi dell’Antico Testamento ci hanno restituito l’immagine di un’età creativa e dinamica e di un ambiente vitale e pluralistico, nel quale convivevano espressioni tra loro anche profondamente diverse dello stesso ebraismo, incluso il nascente movimento cristiano 10. Due elementi sono ormai acquisiti alla ricerca contemporanea e costituiscono il punto di partenza di ogni riflessione ulteriore:

(1) Il giudaismo del Secondo Tempio era diviso in correnti di pensiero in dialogo e competizione tra loro.

L'ovvia realtà' e' davanti agli occhi di tutti. Non c'e' ne' mai c'e' stato un unico momento nella storia dell'ebraismo o del cristianesimo in cui essi siano stati delle religioni monolitiche. Oggi parliamo di giudaismo ortodosso, conservativo e riformato e di cristianesemi ortodosso, cattolico e protestante ma anche prima che emergessero queste moderne divisioni esistevano altre divisioni e cosi' lungo tutto il corso della storia.

Nel secondo Tempio - come testimonia Giuseppe - esistevano tre t=distinte tendenze dottrinali: i sadducei, i farisei (con l'ala radicale e militante degli zeloti) e gli esseni. A queste correnti dovremmo aggiungere anche il giudaismo ellenistico (di cui Giuseppe Flavio non tratta concentrandosi sull'ambiente palestinese) e il movemento gesuano la cui distintivita' certo nessuno vorra' negare all'interno del giudaismo del Secondo Tempio in nome di un rigido monolitismo.

Certamente assieme alla visione monolitica dobbiamo evitare l'estremo opposto, come giustamente rileva Pitta di "considerare ogni variazione cristologica e comportamentale nelle prime comunita' cristiane come forma autonoma di giudaismo e di cristianesimo" (p.24P In media virtus dicevano gli antichi e cosi' e' vero anche in questo campo. Se non si puo' negare la diversita' non si puo' nemmeno arrivare arrivare all'assurdo che esista una forma diversa di giudaismo o di cristianesimo per ciascuno dei testi pervenutivi o dei leader conosciuti o di ogni piu' piccola sfumatura di pensiero. Esistono tuttavia delle grandi famiglie all'interno di ogni religione che portavano avanti visioni diverse delle stessa religione. L'ovvia realtà' e' davanti agli occhi di tutti. Non c'e' ne' c'e' mai statoun unico momento nella storia in cui l'ebraismo o il cristianesimo siano state delle religioni monolitiche. Oggi come ieri

Personalmente trovo un po' oziosa la discussione semantica sull'uso del singolare (varieta' di giudaismo e di cristianesimo) o del plurale (giudaismi o cristianesimi). Che se li chiami "giudaismi" o varietà' diverse di giudaismo" la sostanza non cambia. Al tempo d'oggi come al tempo di Gesu' non esisteva un solo modo di intendere il giudaismo ma modi diverse tra loro in dialogo o in competizione (o giudaismi). E quando il movimento di Gesu; emerse le stesse divisioni ben presto si rifletterono all'interno della nuova sette producendo diverse forme di cristianesimo (o cristianesimi)

Molti studiosi usano oggi comunemente il plurale, "giudaismi", a indicare la grande varietà di pensiero del giudaismo nel primo secolo e le varie movimenti religiosi nel quali l'ebraismo del tempo si divideva. E' questa un'idea oggi universalmente accettata nel mondo degli studi. Anche chi come Sacchi o Pitta conserva remore semantiche sull'uso del plurale applicato al termine "giudaismo", non nega la sostanza del problema, che cioè la religione ebraica del tempo fosse estremamente variegata. Che si parli quindi di "giudaismi" o di "correnti giudaiche" in discorso non cambia. In particolare, siamo oggi messi in guardia da ogni visione monolitica costruita sulle più tardive fonti rabbiniche11.

(2) Il movimento di gesu e' parte integrante del pluralismo giudaico del Second Tempio.

Una volta liberatici dai pregiudizi interpretativi e teologici del passato, ci troviamo di fronte ad alcune scoperte sorprendenti. Ad esempio, molte di quelle che eravamo abituati a considerare idee “tipicamente” paoline e anti-giudaiche (quali la giustifi cazione per fede, il peccato originale e la drammatica percezione dell’insufficienza dell’obbedienza alle norme della Torah ai fini della salvezza) si sono rivelate essere idee diffuse anche in altri ambienti e gruppi giudaici del tempo, spesso con alle spalle

S. Stowers, A Rereading of Romans, Yale University Press, New Haven, CT 1994; J.G. Gager, Reinventing Paul, Oxford University Press, Oxford 2000. 9 P. Eisenbaum, Paul Was Not a Christian: The Original Message of a Misunderstood Apostle, HarperOne, New York, NY 2009. 10 P. Sacchi (ed.), Gli apocrifi dell’Antico Testamento, 5 voll., UTET, Torino (poi Paideia, Brescia) 1981-2000; C. Martone, Testi di Qumran, Paideia, Brescia 1996. 11 G. Boccaccini, Roots of Rabbinic Judaism, Eerdmans, Grand Rapids 2002 (tr. it. I giudaismi del Secondo Tempio, Morcelliana, Brescia 2008). 6.Theme Section - Boccaccini.indd 105 08/05/2012 09:27:06 106 GABRIELE BOCCACCINI

una storia secolare. Ma anche di fronte alle idee "nuove" elaborate all'interno del nascente movimento cristiano sarebbe metodologicamente scorretto considerare come non-giudaica (o non più giudaica) ogni idea che non abbia un parallelo con altri autori o testi giudaici del tempo. Con questo criterio nessuno pensatore originale ebraico sarebbe più ebreo nel momento in cui elabora nuove idee rispetto alla tradizione ricevuta. Non lo sarebbe Filone, Giuseppe Flavio o Hillel. Lo stesso vale per Gesu o Paolo. Il fatto stesso che abbiano elaborato idee originali le rende certo distintive del nuovo movimento ma non per questo meno giudaiche. Va rigettato ogni tentativo di applicare una diversa misura nell'interpretazione delle origini cristiane rispetto alle altre forme di giudaismo contemporaneo.

Chiarite queste premesse metodologiche e' possibile un tentativo di lettura di Paolo non semplicemente in rapporto al giudaismo o nel suo contesto giudaico ma come parte integrante di esso. Se il cristianesimo non si fosse mai sviluppato come religione autonoma, questo sarebbe il modo in cui oggi leggeremmo Paolo, come un autore ebraico del Secondo Tempo, come il Maestro di giustizia o Filone, dei quali nessuno mette in discussione l'ebraicita' nonostante l'originalità delle loro posizioni. Una lettura teologica odierna di Paolo non può ovviamente prescindere dagli sviluppi posteriori, ma una lettura storica non anacronistica ci spinge a immaginare un tempo in cui il "cristiano" Paolo si collocava su un piano non diverso dall'esseno Maestro di Giustizia, dal fariseo "Hillel" o dal giudeo ellenista Filone. Forse e' giunto il momento che la figura di Paolo sia ricollocata nel suo ambito originario storico di appartenenza

Ci sono segnali evidenti che spingono oggi in questa direzione, Per la prima volta the "Eerdmans Dictionary of Early Judaism" a dura di John J Collins e harlow contiene un articolo su Paolo (a firma di Daniel Harrington) e 4 Enoch: The online Encyclopedia of Second Temple Judaism include gli Studi Paolini alla stessa stregua degli studi su Qumran o su Filone. Una tale inclusivita' sarebbe stata impensabile anche solo alcuni anni fa e si colloca in una linea generale di riappropriazione del nascente cristianesimo al giudaismo del primo secolo, di cui si vedono segnali evidenti a livello internazionale. Il presente studio non ha la pretesa di risolvere tutti i numerosi e complessi problemi della teologia paolina ma di offrire alcuni spunti di riflessione che vadano nella direzione di un contributo ad una lettura della figura di Paolo come uno dei protagonisti maggiori del giudaismo del Secondo Tempio, senza negare l'apporto da egli dato al nascente movimento cristiano. Non si tratta di Porre il Paolo ebreo in contrasto con il Paolo cristiano, ma di ribadire che all'interno della diversità giudaica del Second Tempio i due termini non sono il=n contraddizione ed e' possibile leggere Paolo (e Gesu') come pensatori ebrei ed esponenti di un movimento riformatore ebraico che solo in seguito (e con molto gradualita) si separata' dalle altre forme di giudaismo a formare una religione separata ed autonoma.

L'obiettivo del mio lavoro è quello di abbracciare pienamente il paradigma della Radical New Perspective non come la conclusione, ma come punto di partenza di una riflessione che legga il pensiero di Paolo all'interno del giudaismo del Secondo Tempio. A mio parere, il potenziale di un tale approccio ha appena cominciato a manifestarsi. Abbiamo ancora una lunga strada da percorrere prima di comprendere appieno tutte le sue implicazioni monumentali. Al fine di individuare correttamente Paolo Ebreo nel contesto del variegato mondo del giudaismo del Secondo Tempio, abbiamo bisogno prima di tutto di stabilire una migliore comunicazione tra gli studiosi del Nuovo Testamento e specialisti del Secondo Tempio, due campi di studi che fino ad oggi sono rimasti troppo lontano e

sordo a vicenda. Queste mie riflessioni non hanno certo la pretesa di offrire una spiegazione esaustiva del complesso pensiero paolino, ma di indicare piuttosto una scelta metodologica

(2) Tre Avvertenze circa l'ebraicità di Paolo

Alla luce di queste osservazioni possiamo ora riassumere Da questo documento si concentra sulla ebraicità di Paul, è importante chiarire, come premessa, ciò che la riscoperta dell'ebraicita' non dovremmo implica da tale, per evitare equivoci comuni.

(a) Al fine di recuperare l'ebraicità di Paolo non abbiamo a dimostrare che era un Ebreo come tutti gli altri, o che non era un pensatore originale. È importante non applicare a Paul uno standard differente rispetto a qualsiasi altro Ebreo del suo tempo. Affermare che trovare qualche idea in Paul che non ha eguali in altri autori ebrei rende Paolo "non-ebrei", porterebbe al paradosso che nessun pensatore originale del giudaismo del secondo tempio dovrebbe essere considerato "ebreo" - non certo Filone o Giuseppe o Hillel o il Maestro di Giustizia, i quali anche formulato "originali" risposte alle domande più comuni della loro età. Perché solo Paul essere considerato "non-ebrei" o "non-più-ebraica" semplicemente perché ha sviluppato una riflessione originale? La nozione stessa di fare una distinzione all'interno Paolo tra idee suo ebraico e "non-ebrei" (o "cristiani") non ha alcun senso. Paul era ebreo nelle sue idee "tradizionali" e rimase tale anche nella sua "originalità". Paolo era un pensatore ebreo e tutte le sue idee (anche il non-conformisti più) erano ebrei

(b) Al fine di recuperare l'ebraicità di Paolo che non dobbiamo sottovalutare il fatto che egli era una figura molto controversa, non solo all'interno giudaismo del Secondo Tempio, ma anche all'interno del movimento di Gesù. L'interpretazione classica che la natura controversa di Paolo (sia all'interno che all'esterno il suo movimento) invocato il suo tentativo di separare il cristianesimo dal giudaismo non tiene in considerazione la diversità del Secondo Tempio di pensiero ebraico. Non c'è mai stato un ebraismo monolitico contro un cristianesimo altrettanto monolitico. Ci sono state molte diverse varietà del giudaismo (tra cui il movimento di Gesù all'inizio, che a sua volta era anche molto diversa nelle sue componenti interni). La critica e' arma tipica di tutti i movimenti riformatori o d'opposizione; lo fanno i farisei, gli esseni. Lo fa anche Paolo.

(c) Al fine di recuperare l'ebraicità di Paolo non dobbiamo dimostrare che non aveva nulla da dire agli ebrei e che la sua missione era finalizzato solo l'inclusione di Gentili. Come Daniel Boyarin ci ha ricordato nel suo lavoro di Paul, un Ebreo è un Ebreo, e rimane un Ebreo, anche quando lui o lei esprime radicale autocritica verso la propria tradizione religiosa o contro altre forme competitive di ebraismo (Boyarin 1994 ). Limitare l'intero discorso teologico paolino alla sola questione dell'inclusione dei Gentili sarebbe ancora una volta limitare Paolo Ebreo ai margini del giudaismo e oscurare le tante implicazioni della sua teologia nel più ampio contesto del Secondo Tempio di pensiero ebraico.

(3) La "conversione" di Paolo nel contesto dei "giudaismi" del suo tempo

Non fu conversione dal giudaismo al cristianesimo

L'accento sulla diversità giudaica del primo secolo permette in primo luogo di rileggere con un'ottica diversa il problema della conversione di Paolo. E' oggi universalmente accettato dagli studiosi che Paolo mai intese la propria esperienza come un passaggio da una religione all'altra, dall'ebraismo al cristianesimo. E questo non fosse altro che per il semplice fatto che il cristianesimo non esisteva allora come religione distinta dall'ebraismo, essendo il movimento gesuano un movimento messianico all'interno del giudaismo stesso. In questo senso Paolo non intese mai "convertirsi", nel senso di abbandono della proprie religione per abbracciarne un'altra

La conversione come passaggio da una religione all'altra era un'esperienza ben conosciuta nell'antichità, sia nel giudaismo che nel mondo greco-romano. (Giuseppe ed Aseneth, Filone) e l'Asino d'Oro di Apuleio. In entrambi i casi il tema e'quello del completo abbandono del proprio popolo, della propria famiglia e della propria identita' per intraprendere un cammino di radicale "metamorfosi" che porta all'acquisizione di un nuovo popolo, di una famiglia e di una nuova identita'.

Filone di "trattare con rispetto" i proseliti, giacche' "essi hanno abbandonato il proprio paese, i loro amici e le loro relazioni" per acquisire virtu e santita' (Spec Leg I 51-53)

Non e' tuttavia a questi testi che dobbiamo guardare per comprender e l'esperienza di Paolo. Paolo continua a reclamare la propria ebraicita anche dopo la "conversione" e in lui sono del tutto assenti questi elementi di rottura con il proprio popolo, la propria religione e la propria famiglia di origine che abbiamo visto in Giuseppe e Asenath e Filone. Anche dopo la propria conversione Paolo riafferma la propria appartenenza (religiosa ed etnica) al popolo ebraico.

Come afferma Pesce: "Paolo non si e' mai convertito... non usa mai la parola greca metanoia o il verbo metanoein per definire il proprio cambiamento... Paolo non fu un apostata... Paolo vive e interpreta l'esperienza della rivelazione che cambia la sua vita come un fatto interno alla sua esperienza giudaica... La rivelazione [ricevuta] in nessun modo attenua il suo modo di essere giudeo e tanto meno lo abolisce e neppure lo pone in crisi... Paolo era e rimaneva soltanto ebreo" (Pesce, pp.13-32)

In cosa consiste dunque l'esperienza sulla via di Damasco?

< Con la sua “conversione” quindi Paolo mai intese di cambiar religione, semmai decise di mutare la propria appartenenza da un gruppo giudaico (quello dei farisei, al quale aveva aderito con zelo militante) a un altro gruppo giudaico (quello dei seguaci di Gesù, al quale ora aderisce con lo zelo militante del convertito sulla via di Damasco). Da tutto questo consegue che, come nel caso di Gesù, anche la domanda sull’ebraicità di Paolo debba essere posta oggi in termini nuovi. Il problema non è se e in che misura egli possa essere considerato ebreo, ma che tipo di ebreo egli fosse, giacché nel primo secolo vi erano molti modi diversi – e tutti ugualmente legittimi – di essere ebrei.>

Da fariseo a seguace di Gesu'

L'epistolario paolino e gli Atti degli Apostoli ci forniscono un quadro coerente del Paolo "pre-cristiano". Paolo e' un ebreo di Tarso Paolo era un Ebreo ", della tribù di Beniamino » (Rm 11,1; Fil 3,5) . Ha vissuto nella diaspora , come cittadino nativo e di Tarso , la capitale della provincia romana di Cilicia ( Atti 9:11 ; 21:39 , 22:03 ) . Negli Atti , Paolo vanta ripetutamente il suo status di cittadino romano , che gli ha concesso i privilegi e la tutela del diritto romano ( At 16 , 22 ) , e sostiene che ha ereditato la cittadinanza romana dal padre ( "Sono nato un cittadino " Atti 22:28 ) . Come al solito tra gli ebrei della Diaspora , Paolo era conosciuto con il suo nome ebraico " Saul" ( שָׁאוּל ) e il suo nome greco Paulos ( Παῦλος ; . Lat Paulus ) . Nato e cresciuto in una famiglia ebrea , fin da piccolo Paolo era probabilmente un membro della comunità ebraica locale e fu istruito nella lettura della Bibbia in greco ( ed ebraico ? ) . Era certamente fluente sia in ebraico / aramaico e greco . Sembra probabile dai suoi scritti , che ha anche ricevuto qualche tipo di educazione retorica greca , ma nessun riferimento specifico è fatto in fonti antiche .

Quanto alla sua collocazione specifica all'interno del variegato mondo del giudaismo del Secondo Tempio, anche in questo caso le fonti offrono una risposta unitaria. Paolo si definisce "un fariseo " (Fil 3,5) e così lo fa ripetutamente anche negli Atti , dove Paolo si auto=definisce "fariseo, figlio di farisei" e viene anche affermato che ha vissuto a Gerusalemme e fu allievo di Gamaliele . Filippesi ( 3,4-6 ) offre una sorta di riassunto della vita giovanile di Paul . Paolo si riferisce a se stesso come essere " circonciso l' ottavo giorno , un membro del popolo di Israele , della tribù di Beniamino , ebreo da Ebrei , come la legge, fariseo ; [6 ] per zelo , persecutore della chiesa , quanto alla giustizia sotto la legge , irreprensibile " .

Atti introduce bruscamente Paolo come un nemico della Chiesa , in netto contrasto con l'esempio del primo martire Stefano. Paolo " approvato " l'uccisione di Stefano e membri del movimento precoce Gesù molestata , serve "animato da zelo" i sommi sacerdoti Sadducean ( Anna e Caifa ? ) . Paolo in particolare, è descritto come un protagonista della persecuzione contro la chiesa di Gerusalemme che ha portato gli ellenisti di essere " sparsi in tutta la campagna della Giudea e della Samaria . " Paolo è stato poi inviato a Damasco per studiare la sorte dei cristiani lì . Fu durante il suo viaggio a Damasco , che qualcosa è accaduto a cambiare radicalmente il suo atteggiamento verso il movimento di Gesù . In diversi casi a sue lettere Paolo si riferisce apertamente le sue azioni persecutorie contro i membri del movimento di Gesù prima della sua "conversione" . Paolo era un fariseo ( cfr. primi anni di vita di Paolo ) . La sua affermazione che la sua persecuzione è venuto "fuori zelo" , sembra indicare che Paolo il fariseo fu attratto dagli insegnamenti di zeloti e si unì ai sommi sacerdoti , cioè i sadducei , nella loro campagna contro i membri più radicali del movimento di Gesù . Va notato , tuttavia , che la persecuzione di Paul non hanno come bersaglio tutti i membri del movimento di Gesù , ma solo il partito cristiano - ellenistica guidata da Stefano, che secondo gli Atti 7, è stato accusato di promuovere opinioni radicali riguardo al tempio di Gerusalemme e l'osservanza di la Torah . Il " Ebrei " del movimento di Gesù sono stati esentati ; Atti 5:34-39 sostiene che Gamaliel giocato un ruolo decisivo nel proteggere gli apostoli dall'ira dei Sadducei dopo la morte di Gesù.

La ricostruzione degli Atti e' coerente. Gli apostoli vengono arrestati, ammoniti, minacciati, dalle autorità' sadducee ma i farisei si oppongono ad una totale repressione del dissenso.

La persecuzione colpirà gli apostoli e Giacomo il maggiore, il fratello di Giovanni, verra' messo a morte, solo nel periodo del regno hi Erode Agrippa I (41-44), quando il potere sadduceo potrà' ammantare la repressione religiosa con la ragion di stato.

La descrizione dell'esecuzione di Giacomo, il fratello di Gesu' e' conforme a questo schema. Il sommo sacerdote Anania approfitta della morte del procuratore romano e del breve periodo di interregno prima dell'arrivo del nuovo procuratore per agire di fatto come governatore della provincia. Ma l'esecuzione di Giacomo e' vista come un abuso di potere da parte della componente farisaica che richiedono l'immediata rimozione del sommo sacerdote--richiesta alla quale i Romani prontamente acconsentono sostituendo il potente sommo sacerdote.

La "persecuzione" giudaica contro il nascente movimento cristiano fu dunque essenzialmente una persecuzione sadducea, che soltanto nei confronti di alcune frange cristiane più' radicali può' aver attirato la collaborazione di attivisti "zeloti" farisei come Paolo. Nell'approvare la morte di Stefano e nel perseguitare gli ellenisti cristiani, il fariseo Paolo mostra uno "zelo" che le fonti non attribuiscono a Gamaliele, ma nel perseguitare gli ellenisti cristiani e nel risparmiare gli apostoli non agisce in totale contrasto con la posizione del suo maestro.

(3) La conversione di Paolo

Come nel caso di Gesù, il problema di Paolo non è se fosse un Ebreo o no, ma che tipo di Ebreo egli fosse, perché nel variegato mondo del giudaismo del secondo tempio c'erano molti modi diversi di essere un Ebreo (Boccaccini 1991 ). Secondo le sue stesse parole Paolo fu educato come un fariseo. L'idea che Paolo abbia abbandonato l'ebraismo quando "convertito" in movimento di Gesù è semplicemente anacronistico.

La conversione come esperienza di abbandono radicale di identità religiosa e etica di uno è stato effettivamente conosciuta nell'antichità (come attestato in Giuseppe e Aseneth, e nelle opere di Filone). Ma questa non e' stata l'esperienza di Paolo. Cristianesimo il suo tempo è stato un movimento messianico ebreo, non una religione separata. Paul, che è nato e cresciuto un Ebreo, è rimasta tale dopo la sua "conversione"; nulla è cambiato nella sua identità religiosa ed etnica. Che cosa è cambiato però era la sua visione dell'ebraismo. Nel descrivere la sua esperienza non come una "chiamata profetica", ma come una "rivelazione celeste," Paolo si indicava la radicalità della manifestazione. Paul non ha abbandonato l'ebraismo, ma "convertito" da una varietà del giudaismo a un altro.

Ancora Pesce: "Non si tratta di qualcosa che lo faccia uscire dal giudaismo, ma invece di qualcosa che lo orienta a prendere una strada precisa all;interno del giudaismo stesso" (Pesce, 25)

Con Alan Segal, Sono d'accordo che "Paolo era un farisaico Ebreo convertito al nuovo apocalittico, setta ebraica" (Segal 1990).

La radicalita' come segno della "conversione" paolina=

In nessun modo si dovrebbe minimizzare sottovalutare l'importanza della manifestazione e il suo impatto nella vita di Paolo. E 'stata una conversione che rimane all'interno del giudaismo ma che tuttavia ebbe l'effetto di riorientare completamente tutta la vita e la visione del mondo di Paolo. Non e' la religione ebraica cio' che dopo l'incontro con il Cristo appare a Paolo "perdita" e "spazzatura" (Fil 3:7-8), ma e' pur tuttavia una certa visione del giudaismo che appare a lui tale. Se un ebreo ortodosso diventa riformato, o se Woody Allen in un incubo onirico della sua fantasia si immagina trasformato in un rabbino ultra-ortodosso, anche noi descriviamo questa esperienza in termini di "conversione". Se la conversione di Paolo non deve in alcun modo essere intesa come un capitolo nella separazione tra cristianesimo ed ebraismo, essa rappresenta al contrario un evento rilevante nel contesto della diversità del giudaismo del secondo tempio.

Occorre tuttavia a mio giudizio rifuggire anche da posizioni che tendono a minimizzare la conversione di Paolo "riducendola" ai termini di una chiamata che avrebbe indirizzato Paolo ad un missione verso i Gentili ma non modificato nella sostanza dil suo modo di interndere il giudaismo. Paolo non e' fariseo cui e' stato rivelato l'identita' del Messia ed il cui unico scopo nella vita e' ora di annunciare la buona novella ai gentili.

Paolo era e rimase un ebreo prima e dopo la sua conversione. Non lo stesso può' dirsi della sua identita' farisaica. Lungi dall'essere la roccaforte del legalismo ed el conservatorismo, Il fariseismo e' stato uno dei principali movimneti di riforma adel Secondo L'accesa competizione tra Farisei e cristiani deriva proprio dal fatto dall'avere molti punti in comune edal condividere la stess urgenza riformatrice. Certo ci sono degli elementi farisaici nel pensiero di Paolo. Di questo Paolo sapra' ricordarsenea ll'occorrenza, come quando di fronte al Sinedrio affermera' di essere accusato di credere in qialcosa dalla prte dei farisei stategia opportunistica per dividere il campo dei suoi acusatori ed attirarsi la simpatia dei farisei ricordando i numerosi punti in comune tra il movimento gesuano e il farisaismo.

In questo contesto la conversione di Paolo non puo' essere ridotta a una chiamata. Ebbe effetti dirompenti sulla visione del mondo di Paolo

Con la sua “conversione” quindi Paolo mai intese di cambiar

religione, semmai decise di mutare la propria appartenenza da un gruppo

giudaico (quello dei farisei, al quale aveva aderito con zelo militante) a

un altro gruppo giudaico (quello dei seguaci di Gesù, che aveva perseguitato e al quale ora aderisce con lo zelo militante del convertito sulla via di Damasco).

Conclusione

Paolo era un fariseo (con tendenze zelote) che ha aderito al movimento di Gesù. Passeranno pero' molti anni prima che Paolo sia conosciuto come l'apostolo delle genti ed acquisisca un ruolo di leadership all'interno del movimento gesuano. Nella Lettera ai Galati Paolo afferma di essersi recato in Arabia e qauindi di essere tornato a Damasco. Dopo tre anni Paolo si reca una prima volta a Gerusalemme da cristiano "per visitare Pietro e stare con lui 15 giorni". Paolo ebbe anche modo di incontrare Giacomo, il fratello di Gesu', ma non vide nessun altro apostolo (Gal 1:

Passano altri 14 anni che Paolo dice di aver trascorso "nelle regioni di Siria e della Cilicia". Lo ritroviamo quindi con Tito a Gerusalemme tra coloro che accompagnano Barnaba, il leader riconosciuto della comunita' cristiana di Antiochia. A questo punto Paolo si presenta come parte di un gruppo che all'interno della primo cristianesimo si e' andato caratterizzando per una particolare attenzione per la missione verso i Gentili.

Prima di Paolo l'apostolo dei gentili, c'era Paolo "il seguace di Gesù" e il Paolo "membro della comunita' di Antiochia". Ogni discorso su Paolo non può quindi evitare la questione di ciò che il movimento di Gesù stava nel contesto del giudaismo del secondo tempio e del ruolo assunto dalla comunita' di Antiochia nella sua particolare apertura ai gentili

CAPITOLO II

Cap. 2. Paolo il seguace di Gesu'; il periodo formativo

Siamo tutti d'accordo che, al suo inizio, il cristianesimo è stato un movimento messianico ebreo, ma che cosa significa esattamente? Sarebbe semplicistico ridurre il messaggio primi "cristiani" ad un annuncio generiche sulla venuta imminente del regno di Dio, e di Gesù come il Messia atteso. E sarebbe riduttivo immaginare Paolo come un fariseo a cui una particolare attenzione per la missione per i pagani. è stato rivelato il nome del futuro Messia e che credeva di vivere alla fine dei tempi.

Come risultato della sua "conversione", Paul pienamente abbracciato la visione del mondo apocalittica cristiana e l'affermazione che Gesù il Messia era già venuto (e sarebbe tornato alla fine dei tempi). Questa comprendeva la spiegazione del perché il Messia era venuto prima della fine. I primi cristiani avevano una risposta; Gesù non è venuto semplicemente a rivelare il suo nome e l'identità. Gesù è venuto come il Figlio dell'uomo, che aveva "il potere sulla terra di rimettere i peccati" (Mc 2 e paralleli).

<> Un dibattito ebraico Secondo Tempio <>

L'idea del Messia come perdona sulla terra perfettamente senso come uno sviluppo dell'antica tradizione apocalittica enochico. Il "contro-narrazione" di 1 Enoch incentrata sul crollo dell'ordine creativa da una ribellione cosmica (il giuramento e le azioni degli angeli caduti) apocalittica: "Tutta la terra è stata corrotta dall'insegnamento di Azazel dei suoi [propri] azioni ; e scrivere su di lui tutto il peccato "(1 En 10:. 8). Era questa ribellione cosmica che ha prodotto la catastrofe del diluvio, ma anche la necessità di una nuova creazione.

La visione enochico dell'origine del male ha profonde implicazioni per lo sviluppo del Secondo Tempio di pensiero ebraico. L'idea della "fine dei tempi" è oggi tanto radicata nelle tradizioni ebraica e cristiana per rendere difficile persino immaginare un tempo in cui non era, e di comprendere appieno l'impatto rivoluzionario quando prima emerse. Nelle parole della Genesi, nulla è più perfetto del mondo perfetto, che Dio stesso ha visto e ha elogiato come "molto buona" (Gen 1,31). Nessuno avrebbe cambiato qualcosa che "funziona", a meno che qualcosa è andato terribilmente storto. Nel pensiero apocalittico, l'escatologia è sempre il prodotto di protologia.

Il problema di enochico dell'ebraismo con la Legge mosaica è stato anche il prodotto di protologia. Esso non è venuto da una critica diretta della legge, ma dal riconoscimento che la ribellione angelica aveva reso difficile per le persone a seguire le leggi (compresa la Toràh mosaica) in un universo ormai sconvolto dalla presenza del male sovrumana. Il problema non era la Torah in sé, ma l'incapacità degli esseri umani di fare buone azioni, che colpisce il rapporto umano con il Mosaico Torah. Lo spostamento della messa a fuoco non è stato in primo luogo da Mosè a Enoch, ma dalla fiducia nella responsabilità umana al dramma della colpevolezza umana. Mentre al centro del Mosaico Torah è stata la responsabilità umana di seguire le leggi di Dio, al centro di enochico ebraismo era ora un paradigma di vittimizzazione di tutta l'umanità.

Questo è il motivo non sarebbe corretto parlare di enochico giudaismo come una forma di ebraismo "contro" o "senza" la Torah. Enochico ebraismo non era "in competizione saggezza", ma più propriamente una "teologia della denuncia." Non c'era halakhah enochico alternativa a questo mondo, nessun codice purezza enochico, non enochico Torah; ogni speranza di redenzione è stata rinviata alla fine dei tempi. I Enochians non erano in competizione con Mosè, non facevano altro che lamentarsi. Nel Libro di enochico I sogni, il popolo eletto di Israele è promesso un futuro di riscatto nel mondo a venire, ma in questo mondo Israele è influenzato dalla diffusione del male, senza la protezione divina, come tutte le altre nazioni sono.

La vista enochico aveva risvolti inquietanti nel autocomprensione del popolo ebraico, come il popolo dell'alleanza. Ha generato un acceso dibattito all'interno del giudaismo circa l'origine e la natura del male (Rosen-Zvi 2011; Capelli 2012; marca 2013). Molti (come i farisei ei sadducei) respinto l'idea stessa di origine sovrumana del male; alcuni esplorato altre strade per salvare la libertà umana e l'onnipotenza di Dio percorsi che hanno portato a soluzioni alternative, dal malignum cor di 4 Esdra al yetzer hara rabbinico. Anche nei circoli apocalittici, c'erano teologie in competizione. Verso la metà del II secolo aC il Libro dei Giubilei ha reagito contro questa scomparsa del rapporto di alleanza con Dio attraverso la creazione di una sintesi efficace tra Enoch e Mosè, che molti studiosi vedono come la fondazione del movimento esseno. Pur mantenendo la struttura enochico di corruzione e di degrado, Giubilei reinterpretato il patto come "medicina" fornita da Dio di risparmiare al popolo eletto dal potere del male. La fusione di Mosaic e tradizioni enochico ridefinito uno spazio, in cui il popolo di Israele potrebbe ora vivo protetto dalla malvagità del mondo sotto le mura di un halakhah alternativo, finché sono rimasti fedeli alle regole imposte. L'alleanza è stata restaurata come pre-requisito per la salvezza. A questo proposito, come dice Collins, "Giubilei, che racconta le storie della Genesi da una prospettiva decisamente Mosaico, con interessi halachiche espliciti" stavano "in netto contrasto" alla tradizione enochico (Collins 2007). Ancora più radicale la Regola comunitario esplorare la predestinazione come un modo per neutralizzare la perdita di controllo del mondo creato da Dio e ripristinare l'onnipotenza di Dio (Boccaccini 1998).

Enochico ebraismo è rimasto fedele alle proprie sedi (ebrei e gentili sono ugualmente colpiti dal male), ma non era insensibile alle critiche di aver dato troppo potere al male e, quindi, riducendo drasticamente le possibilità umane di essere salvati. La tradizione enochico successivamente cercato di risolvere il problema seguendo un percorso diverso. Nelle parabole di Enoch si legge che alla fine dei tempi nel Giudizio, come previsto, Dio e il suo Cristo Figlio dell'uomo salverà i giusti e condannare gli ingiusti. I giusti sono "d'onore" (di merito, le buone opere) e sarà vittorioso in nome di Dio, mentre "i peccatori" non hanno onore (senza le buone opere) e non verranno salvati in nome di Dio. Ma inaspettatamente nel cap. 50 un terzo gruppo emerge al momento del Giudizio. Essi sono chiamati "gli altri"; sono peccatori che si pentono e abbandonano le opere delle loro mani. "Non avranno onore alla presenza del Signore degli Spiriti, ma attraverso il suo nome saranno salvati, e il Signore degli Spiriti avrà pietà di loro, perché grande è la sua misericordia" (Boccaccini 2013). In altre parole, il testo esplora il rapporto tra giustizia e misericordia di Dio e il ruolo svolto da questi due attributi di Dio nella sentenza. Secondo il Libro delle Parabole, i giusti sono salvati in base alla giustizia di Dio e la Misericordia, i peccatori sono condannati in base alla giustizia di Dio e la misericordia, ma coloro che si pentono saranno salvati per la misericordia di Dio, anche se non devono essere salvati in base alla giustizia di Dio. Il pentimento fa prevalere la misericordia di Dio sulla giustizia di Dio.

Il Gesu' storico

Il dibattito sul Gesu' storico e' oggi piu' acceso che mai. In alcuni circoli e per gran parte dell'opinione fa ancora scandalo l'idea che Gesu' nacque, visse e mori' da ebreo.

Gli studiosi oggi concordano sull'ebriacita' di Gesu', ma si dividono nell'indicare quale tipo di ebreo egli fosse. Da un lato ci si interroga su quanto il Gesu' storico abbia coscientemente partecipato al dibattito teologico giudaico del suo tempo o ne sia stato "marginale". Dall'altro, si discute se e in che misura il Gesu' dei Vangeli rifletta il pensiero del Gesu' storico o lo adatti o lo tradisca o addirittura lo reinventi totalmente, e in particolare se l'apocalitticita' del pensiero gesuano sia un tratto aggiuntivo o costitutivo del suo messaggio. Anche in Italia i migliori specialisti, da Mauro Pesce a Paolo Sacchi, per anni si sono confrontati su queste domande. Sono problemi aperti, forse irrisolvibili, che riserviamo ad altra occasione.

Per la nostra riflessione su Paolo e' importante notare come le antiche fonti cristiane post-pasquali concordino nel presentare la figura di Gesu' in chiave apocalittica.