Difference between revisions of "Category:New Testament (subject)"

| (2 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

[[File:Old and New Testament.jpg|thumb|400px|The | [[File:Old and New Testament.jpg|thumb|400px|The Christian Bible:The Old and New Testaments]] | ||

[[File:Codex Sinaiticus.jpg|thumb|400px|The Codex Sinaiticus: The earliest extant collection of the New Testament, 4th cent.]] | [[File:Codex Sinaiticus.jpg|thumb|400px|The Codex Sinaiticus: The earliest extant collection of the New Testament, 4th cent.]] | ||

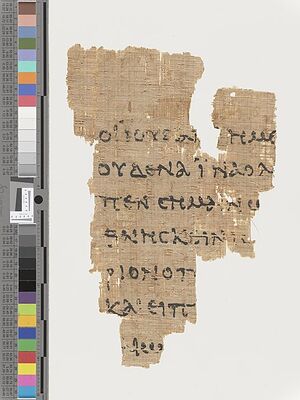

[[File:Rylands Library Papyrus P52.jpg|thumb|300px|The Rylands Library Papyrus P52: The earliest extant fragment of a New Testament text, the Gospel of John, 2nd cent.]] | |||

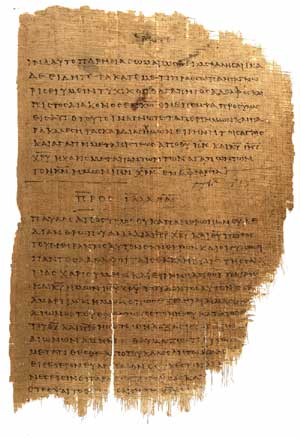

[[File:Michigan Library Papyrus P46.jpg|thumb|300px|The University of Michigan Library Papyrus P46: One of the earliest extant fragments of a New Testament text, the letters of Paul, 2nd cent.]] | |||

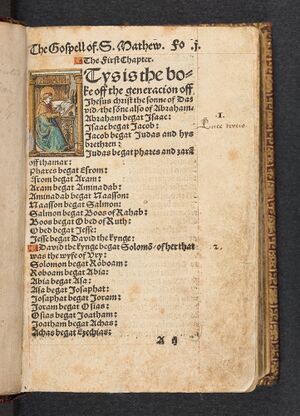

[[File:1526 Tyndale.jpg|thumb|300px|The first English Translation of the New Testament from the original Greek text, by William Tyndale, 1526]] | |||

*[[:Category:Texts|BACK TO THE TEXTS--INDEX]] | *[[:Category:Texts|BACK TO THE TEXTS--INDEX]] | ||

Latest revision as of 11:11, 5 January 2023

The New Testament is the central collection of religious texts of Christianity.

- Gospel of Matthew / Gospel of Mark / Gospel of Luke / Gospel of John

- Acts of Apostles

- Letter to the Romans / 1 Corinthians / 2 Corinthians / Letter to the Galatians / Letter to the Philippians / 1 Thessalonians / Letter to Philemon

- Letter to the Ephesians / Letter to the Colossians / 2 Thessalonians

- 1 Timothy / 2 Timothy / Letter to Titus

- Letter to the Hebrews

- Letter of James / 1 Peter / 2 Peter / 1 John / 2 John / 3 John / Letter of Jude

- Revelation of John

Overview

What Is the New Testament?

The "New Testament" is the traditional name given to the second part of the Christian Bible, containing the writings of the early Christian community. The term New Testament distinguishes this section from the “Old Testament” (or Hebrew Bible), which contains the texts that early Christians inherited from the previous Jewish tradition. Although the product of human authors, Christians regard these texts as divinely inspired and containing the authentic revelation of Jesus of Nazareth.

The word “Testament” derives from the Latin (testamentum); it means, “covenant”.

The New Testament is not a single book, but a collection of 27 books. Although all of them refer to Jesus of Nazareth, none of them was authored by Jesus himself. Jesus was a preacher, not a writer; he did not leave any writings, nor dictated any texts.

The texts in the New Testament were written by disciples and believers in Jesus. None of them was written by independent witnesses or non-Christians. In this sense, they are biased: the goal of the authors of the NT texts was to preach the Christian message.

The documents in the New Testament are very different from one another (different literary form, or genres). There are biographies of Jesus (the Gospels), letters, a survey of Church history, one apocalypse. What they have in common, is the reference to Jesus and to the religious movement he initiated. The NT is a collection of Christian religious texts.

The most represented author in the NT is Paul, to whom 13 letters are attributed.

The documents in the New Testament were written roughly between 50 and 150. The new Testament does not include all Christian documents written during that time. The New Testament is a “canon”, i.e. an authoritative collection, or better, selection of documents.

The Formation of the Canon

The formation of the New Testament was a gradual process. It took three centuries before the leaders of the Church defined the accepted canon of the New Testament. The first evidence of the canon of 27 books comes from a letter of the bishop of Alexandria, Athanasius, in 367 CE.

- “It is not tedious to speak of the books of the New Testament. These are, the four Gospels, according to Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John. Afterwards, the Acts of the Apostles and Epistles (called Catholic), seven, viz. of James, one; of Peter, two; of John, three; after these, one of Jude. In addition, there are fourteen Epistles of Paul, written in this order. The first, to the Romans; then two to the Corinthians; after these, to the Galatians; next, to the Ephesians; then to the Philippians; then to the Colossians; after these, two to the Thessalonians, and that to the Hebrews; and again, two to Timothy; one to Titus; and lastly, that to Philemon. And besides, the Revelation of John.” (Athanasius, Easter Letter, A.D. 367)

Before the fourth century the situation was rather fluid. Each Christian community had its own “canon” that often included either a limited number of texts or texts later rejected. Each canon reflected the theological diversity of the Church. There was a great deal of diversity in the early Church. Groups such as the Marcionites or the Gnostics or the Jewish Christians had their own distinctive canon in competition with other Christian groups. For example, the Nag Hammadi Library was a Gnostic Library, discovered in 1945 in Egypt. It contains some fifty-two documents written in Coptic. It gives us an idea of the canonical writings of a Christian Gnostic Community in the first four centuries of the Common Era—documents that were later rejected by the Church.

The creation of a unified canon was prompted in the fourth century by historical factors. Christianity became the official religion of the Roman Empire. The Emperor required unity of Christian organization and belief.

In order to define the canon of the New Testament the Church used two major criteria:

- apostolicity, or antiquity (in order to 'canonical a text had to be written by an apostle, or in the name of an apostle)

- recognition, or orthodoxy (the authority of a text had to be recognized by the majority of the Churches)

The apostles were considered the eyewitness of Jesus. Among the apostles were reckoned not only the Twelve but also the members of the family of Jesus (James, Jude) and Paul. According the early Christian tradition the risen Christ appeared not only to the Twelve but also to James, the brother of Jesus. Paul also was considered an apostle because of his authority and importance in the early Church, even though he had never met Jesus. However, according to the early Christian tradition Paul saw the risen Jesus in a vision; he was then considered to be an apostle.

Ancient Christians knew that many authors of the text in the New Testament were neither apostles nor eyewitnesses. Authors such as Mark or Luke were disciples of the apostles; their works were included because they were believed to reflect the teaching of an apostle.

- "Mark having become the interpreter of Peter, wrote down accurately whatsoever he remembered. It was not, however, in exact order that he related the sayings or deeds of Christ. For he neither heard the Lord nor accompanied Him. But afterwards, as I said, he accompanied Peter, who accommodated his instructions to the necessities [of his hearers], but with no intention of giving a regular narrative of the Lord's sayings. Wherefore Mark made no mistake in thus writing some things as he remembered them. For of one thing he took especial care, not to omit anything he had heard, and not to put anything fictitious into the statements." (Papias in Eusebius, Ecclesiastical History, 4th cent.).

In some cases the authority of an ancient text was recognized but not its apostolicity. Because of this, texts such as the Letter of Clement, the letter of Barnabas, etc. were not included in the NT but continued to be used in the Church. They are known as the “Apostolic Fathers”

In some cases the apostolicity of an ancient text was recognized but not its authority. Because of this, texts such as the Gospel of Thomas, the Apocalypse of Peter, etc., which were attributed to Jesus’ apostles but whose authority was not universally recognized, were excluded and their usage in the Church discouraged. These texts are known as “New Testament Apocrypha”.

In addition, not all potentially canonical texts have been preserved. Some were lost. For example, in 1 Corinthians Paul says that he had previously written a letter to that Church—letter that is no longer extant.

Within the canon of the New Testament, texts were not arranged according to the chronological order of composition, but according to their content: first, the Gospels; than, the historical book (the Acts) and Paul, and then the letters (including, at the end, Revelation). The order of the New Testament was modeled after the Hebrew Bible, which is also divided in three parts: Torah, Prophets and Writings (including the apocalyptic Daniel).

The earliest texts in the New Testament are not the Gospels, but the Letters of Paul. The earliest extant letter of Paul is the so-called First letter to the Thessalonians, written around 50 CE.

Language and translation

All NT texts are written in Greek; occasionally they contain some Aramaic words.

The spoken language in 1st century Israel, the language spoken by Jesus and his first disciples, was Aramaic. Hebrew was the language of the ancient Scripture of Israel and was also known. Greek was the international language of communication of the ancient world (like English today, or Latin and French in the past). This explains why the NT texts were written in Greek, even though Jesus preached in Aramaic.

The originals of all books of the New Testament are all lost. What we have, are only copies of copies. The earliest fragments goes back to the 2nd century. Most of the around 5,000 extant manuscripts of the NT are from the Middle Ages.

NT manuscripts contain a lot of careless mistakes. Words are either misspelled, or repeated, or skipped. Copying was a very difficult and tiring job.

In addition, many times Christian scribes had the tendency to transfer back their theology on the text, generating some theologically motivated “corrections”. For instance, as some Christian scribes of later times did not approve of the high profile women occasionally enjoyed in the early churches, they changed the text accordingly. In many manuscripts, the “prominent women” of Acts 17:4 became “the wives of prominent men”, etc. In order to save the omniscience of Jesus, some ancient manuscripts deleted the reference to the Son in Mt 24:36, where is written: “About that day and hour [of the End] no one knows… not event the Son, but the Father alone.”

Scholars reconstruct the “original” text by comparing the many manuscripts between themselves and with ancient translations and quotations by ancient authors, and critically assessing the many variants. Not necessarily the majority reading or the reading attested in the earliest manuscript is the closest to the original.

In antiquity ordinary Christians did not "read" the New Testament. Most people were not educated and copies of the NT were very rare and expansive. Only the richest Monasteries and Parishes could afford to produce or purchase manuscripts. The NT was read by priests and preached in sermons. NT scenes were painted on the walls of the churches for instruction.

The New Testament was known neither in the original Greek nor in the everyday language, but in Latin, which in the West had became the language of the Church, and the reading of the holy texts was restricted to the clergy.

It was only in the 16th century that the NT was translated into modern languages. The Reformation promoted the translation of the Bible. Martin Luther was the author of the first German translation (1522-1534). Around the same time the invention of printing made finally the NT available and affordable to ordinary Christians. But not everybody agreed. When in 1525, William Tyndale translated for the first time the New Testament in English he was tried for heresy and burned at the stake. In the Catholic Church, the reading of the New Testament by ordinary Christians was openly encouraged only after the Second Vatican Council in the 1960s.

The King James Version is an English translation published in 1611 for the official use in the Anglican Church. Is a poetic masterpiece but his language is now largely outdated and his text is not always reliable as it was based on a limited number of ancient manuscripts.

In the 16th century also began the tradition of dividing the text in chapters and verses, which was popularized by the printed editions of the Bible.

External links

Pages in category "New Testament (subject)"

The following 97 pages are in this category, out of 97 total.

1

- The Characteristic Differences of the New Testament from the Immediately Preceding Jewish, and the Immediately Succeeding Christian Literature (1865 Sinker), book

- Bibliotheca Novi Testamenti graeci: cuius editiones ab initio typographiae ad nostram aetatem impressas (1872 Reuss), book

- Cambridge Greek Testament for Schools and Colleges (1881-1933 Cambridge University Press), book series

- American Commentary on the New Testament (1881-1890 American Baptist Publication Society), book series

- Revue Biblique (1892-), journal

- Om källorna til 1541 års öfversättning af Nya Testamentet (1896 Stave), book

- New Testament Handbooks (1899-1910), book series

- Zeitschrift für die Neutestamentliche Wissenschaft (1900-), journal

- The Incarnation of the Lord (1902 Briggs), book

- Licht vom Osten (1908 Deissmann), book

- Biblica (1920-), journal

- Clarendon Bible (1922-1947), book series

- Beihefte zur Zeitschrift für die neutestamentliche Wissenschaft und die Kunde der älteren Kirche

- Apostelbrevene i det Nye Testamente (1926 Schjøtt), book

- Syrus Sinaiticus (1930 Hjelt), book

- Uuden testamentin kreikkalais-suomalainen sanakirja (1939 Gyllenberg), book

- Graecitas biblica (1944 Zerwick), book

- Sanoma Kristuksesta: Uuden testamentin synty ja ajatusmaailma (1947 Gyllenberg), book

- Studiorum Novi Testamenti Societas

- Associazione Biblica Italiana (1948-), learned society

- Suomalainen Uuden Testamentin Selitys (1951-56, 1989-92 Kirjapaja), book series

- Daily Study Bible

- Rivista Biblica (1953-), journal

- New Testament Studies (1954-), journal

- Rippi ja Uusi Testamentti (1954 Sinnemäki), book

- Early Versions of the New Testament (1954 Vööbus), book

- New Testament Abstracts (1956-), journal

- Novum Testamentum (1956-), journal

- Tyndale New Testament Commentaries

- Black's New Testament Commentaries

- Supplements to Novum Testamentum (1958- Brill), book series

- Semitische Syntax im Neuen Testament (1962 Beyer), book

- Studien zur Umwelt des Neuen Testaments

- Archaeology and the New Testament (1962 Unger), book

- New Clarendon Bible (1963-1976), book series

- Biblioteca minima di cultura religiosa

- The New Testament in Historical and Contemporary Perspective (1965 Anderson, Barclay), edited volume

- Humour and Irony in the New Testament (1965 Jakob Jónsson), book

- Understanding the New Testament (1965 Lace), book

- Society for New Testament Studies Monograph Series (1965- Cambridge University Press), book series

- New Testament Illustrations: Photographs, Maps, and Diagrams (1966 Jones), book

- The New Testament and Criticism (1967 Ladd), book

- Guide to the Bible (1968-1969 Asimov), book

- Studi biblici (1968- Paideia), book series

- Guides to Biblical Scholarship (1969-2002), book series

- What is Redaction Criticism? (1969 Perrin), book

- Literary Criticism of the New Testament (1970 Beardslee), book

- La inmortalidad del alma o la resurrección de los cuerpos (1970 Cullman / Requenan), book (Spanish ed.)

- Die Traditionen über Apollonius von Tyana und das Neue Testament (1970 Petzke), book

- Imperial Cult and Honorary Terms in the New Testament (1974 Cuss), book

- The Concept of Spirit: A Study of pneuma in Hellenistic Judaism and Its Bearing on the New Testament (1976 Isaacs), book

- The New Testament Concept of Witness (1977 Trites), book

- New International Greek Testament Commentary (1978- Eerdmans), book series

- Journal for the Study of the New Testament (1978-), journal

- Text and Interpretation: Studies in the New Testament Presented to Matthew Black (1979 Best, Wilson), edited volume

- Journal for the Study of the New Testament Supplement Series

- Þættir um Nýja testamentið (1981 Jakob Jónsson), book

- Abba: El mensaje central del Nuevo Testamento (1981 Jeremias / Ortiz/Vevia/Ruiz-Garrido/Bernáldez/Rey/Martínez), book (Spanish ed.)

- The New Testament World: Insights from Cultural Anthropology (1981 Malina), book

- Studies in the Bible and Early Christianity (1981-2006 Mellen), book series

- Reading the New Testament (1982-2005 Crossroad), book series

- Interpretation: A Bible Commentary (1982-2005 Knox), book series

- Estudios sobre el Nuevo Testamento (1983 Bornkamm / Sauras/Martínez), book (Spanish ed.)

- New Testament Interpretation through Rhetorical Criticism (1984 Kennedy), book

- The New Testament and Early Christianity (1984 Tyson), book

- Novum Testamentum et orbis antiquus

- Initiation à la critique textuelle du Nouveau Testament (1986 Vaganay / Amphoux), book

- The New Testament in Its Literary Environment (1987 Aune), book

- Ética del Nuevo Testamento (1987 Schrage), book (Spanish ed.)

- El mensaje moral del Nuevo Testamento (1988-1989 Schnackenburg), book (Spanish ed.)

- Citazioni patristiche e critica testuale neotestamentaria: il caso di Lc 12,49 (1990 Visonà), book

- An Introduction to New Testament Textual Criticism (1991 Vaganay, Amphoux / Read-Heimerdinger), book (English ed.)

- Let the Oppressed Go Free: Feminist Perspectives on the New Testament (1993 Schottroff / Kidder), book (English ed.)

- La mesa compartida: Estudios del Nuevo Testamento desde las ciencias sociales (1994 Aguirre Monasterio), book

- The Right Doctrine from the Wrong Text? Essays on the Use of the Old Testament in the New (1994 Beale), edited volume

- Studies on Personalities of the New Testament

- The Making of the New Testament (1995 Patzia), book

- El Nuevo Testamento: Introducción al estudio de los primeros escritos cristianos (1995 Piñero Sáenz), book

- Westminster Bible Companion (1995- Westminster), book series

- La Bibbia delle donne: un commentario = The Women's Bible Commentary (1996-99 @1992 Newsom, Ringe / Franzosi), edited volume (Italian ed.)

- Anti-Roman Cryptograms in the New Testament (1997 Beck), book

- Cristología del Nuevo Testamento (1997 Cullmann / Pikaza/Gattinoni), book (Spanish ed.)

- The International Biblical Commentary (1998 Farmer) edited volume

- New Testament Gateway (1997- Goodacre), website

- Of Two Minds: Ecstasy and Inspired Interpretation in the New Testament World (1999 Levison), book

2

- The HarperCollins Bible Commentary (2000 Mays), edited volume

- Jesucristo en el Nuevo Testamento (2002 Karrer), book (Spanish ed.)

- The New Testament as Reception (2002 Müller / Tronier), edited volume

- The Use of the Septuagint in New Testament Research (2003 McLay), book

- Simeon Könyvek (2004- L'Harmattan), book series

- What Are They Saying about New Testament Apocalyptic? (2004 Lewis), book

- The Septuagint, Sexuality, and the New Testament (2004 Loader), book

- The Reluctant Parting: How the New Testament's Jewish Writers Created a Christian Book (2005 Galambush), book

- The Roman Empire and the New Testament: An Essential Guide (2006 Carter), book

- Τά ἀπόκρυφα εὐαγγέλια καί ὁ σχηματισμός τῆς Καινῆς Διαθήκης (2006 Riginiotis), book

- Forged: Writing in the Name of God (2011 Ehrman), book

- El camino de la ley: Del Antiguo al Nuevo Testamento (2011 Granados García), book

Media in category "New Testament (subject)"

The following 5 files are in this category, out of 5 total.

- 1922 * Strack Billerbeck.jpg 432 × 664; 38 KB

- 1978 Sandmel 2.jpg 266 × 399; 20 KB

- 1992-E * Newsom Ringe.jpg 475 × 475; 26 KB

- 1998-E * Newsom Ringe.jpg 500 × 500; 26 KB

- 2012-E * Newsom Ringe Lapsley.jpg 334 × 499; 31 KB