Difference between revisions of "Category:Salome Alexandra (subject)"

| (3 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 24: | Line 24: | ||

|content= | |content= | ||

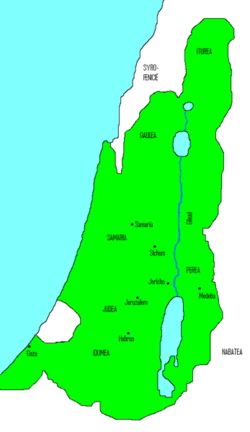

[[File:Salome Alexandra map.png|thumb|250px]] | [[File:Salome Alexandra map.png|thumb|250px]] | ||

Salome Alexandra became Judea’s political ruler in 76 B.C.E. upon the death of her husband, [[Alexander Jannaeus]], during the battle of Ragaba. [[Josephus]] hints that she actually held some political power during her husband’s twenty-seven year reign. He suggests this when he states that Antipas, the grandfather of [[Herod the Great]], came to political power when “king Alexander and his wife made him general of all Idumea.” Salome Alexandra appointed her eldest son, [[John Hyrcanus II]], as high priest. Her younger son, [[Aristobulus II]], commanded her army. | Salome Alexandra became Judea’s political ruler in 76 B.C.E. upon the death of her husband, [[Alexander Jannaeus]], during the battle of Ragaba. [[Josephus]] hints that she actually held some political power during her husband’s twenty-seven year reign. He suggests this when he states that Antipas, the grandfather of [[Herod the Great]], came to political power when “king Alexander and his wife made him general of all Idumea.” Salome Alexandra appointed her eldest son, [[John Hyrcanus II]], as high priest. Her younger son, [[Aristobulus II]], commanded her army. | ||

| Line 46: | Line 45: | ||

Following the creation of the modern State of Israel, Jerusalem’s authorities changed the name of Princess Mary Street to Queen Shlomzion Street to honor Salome Alexandra. In 1977, Ariel Sharon, the former Israeli politician, general, and prime minster, named his now-defunct political party, Shlomtzion (“Peace of Zion”). | Following the creation of the modern State of Israel, Jerusalem’s authorities changed the name of Princess Mary Street to Queen Shlomzion Street to honor Salome Alexandra. In 1977, Ariel Sharon, the former Israeli politician, general, and prime minster, named his now-defunct political party, Shlomtzion (“Peace of Zion”). | ||

'''References''' | |||

''' | |||

''' | * '''Salome Alexandra''' / [[Kenneth Atkinson]] / [[T&T Clark Encyclopedia of Second Temple Judaism (2019 Stuckenbruck, Gurtner), dictionary]] | ||

*'''Alexandra Salome''' / [[Mitchell C. Pacwa]] / In: [[The Anchor Bible Dictionary (1992 Freedman), dictionary]], 1:152 | *'''Alexandra Salome''' / [[Mitchell C. Pacwa]] / In: [[The Anchor Bible Dictionary (1992 Freedman), dictionary]], 1:152 | ||

| Line 68: | Line 63: | ||

{{WindowMain | {{WindowMain | ||

|title= | |title= History of research | ||

|backgroundLogo= Bluebg_rounded_croped.png | |backgroundLogo= Bluebg_rounded_croped.png | ||

|logo = contents.png | |logo = contents.png | ||

| Line 74: | Line 69: | ||

|content= | |content= | ||

[[Azariah de' Rossi]] (16th century Jewish-Italian Writer) is one the first interpreters of Salome Alexandra. He writes: "It is stated that of the Hasmoneans, Johanan the first, also Hyrcanus, was the father of Jannaeus Alexander, the husband of Queen Alexandra. On his deathbed, he advised her to transfer her allegiance from the Sadducees to the Pharisees who would be supportive of her rule. … It would seem that it is to these stories about the man and his wife, which the sages’ statement in tractate Sota refer: “Jannai the king said to his wife, ‘Do not fear the Pharisees or the non-Pharisees, but rather the hypocrites.’” (Joanna Weinberg, trans. The Light of the Eyes [Yale University Press, 2001). | |||

In 1892 rabbi [[Henry Zirndorf]] devoted to the Queen a chapter of his book on “Some Jewish Women.” | |||

In 1972 [[Solomon Zeitlin]] emphasized the many similarities between the fictional character of [[Judith]] and Salome Alexandra. Zeitlin however did not see any major political event in the life of Alexandra that could have prompted such a connection. | |||

The revised edition of Schurer in 1973 also reiterated the view that "no political events of any importance occurred during her reign." | |||

In 2005 [[Samuel Rocca]] first suggested that the story of Judith could contains echoes of the crisis generated by the invasion of the Armenian King [[Tigranes the Great]]. The argument was taken up in 2009 by [[Gabriele Boccaccini]] who drew attention on the Armenian and Roman sources that seem to confirm the chronological and geographical details provided in the Book of Judith about the military campaign of the new "Nebuchadnezzar," [[Tigranes the Great]]. | |||

[[Tal Ilan]] has recently published a book that examines rabbinic accounts of Salome Alexandra, and the various spellings of her name in antiquity. Ernst Axel Knauf has recently proposed that Salome Alexandra’s reign is reflected in canonical Psalms 148 and 2, and that the latter contains an acrostic that mentions her and her husband. | |||

'''The name''' | |||

Until the discovery of the Dead Sea Scrolls Salome Alexandra’s exact name was the subject of a scholarly debate. In Jewish literature she is referred to as Shel-Zion, Shalmonin, Shalmza, Shlamto, and similar names. This confusion led [[Jacob Neusner]] to comment that Salome Alexandra is “…a queen whose name no one can get straight.” In 1899 the French scholar Charles Clermont-Ganneau, proposed that Shelamzion is her Semitic name. The Dead Sea Scrolls now confirm his proposal and mention her twice by this name. | |||

'''Salina or Salome Alexandra?''' | |||

According to Josephus, Salome Alexandra’s husband, Alexander Jananeus, came to the throne under unusual circumstances. He writes of this transition: | |||

Salina, called Alexandra by the Greeks, released Judah Aristobulus’s brothers—for Aristobulus had imprisoned them, as we have said before—and appointed as king Jannaeus, also known as Alexander, who was best fitted for this office by reason of his age and because he knew his place. (Ant. 13.320-1; cf. War 1.85) | |||

Most scholarship on this period accepts the thesis that Salina Alexandra is Salome Alexandra. According to this interpretation she appointed her brother-in-law, Alexander Jannaeus, as king and high priest. She then married him in accordance with the rules of levirate marriage found in Deuteronomy 25. | |||

[[Kenneth Atkinson]] and [[Tal Ilan]] have recently argued that Salina Alexandra is the wife of Salome Alexandra’s brother-in-law, Judah Aristobulus. According to this theory, Salome Alexandra never contracted a levirate marriage with Alexander Jannaeus. The two propose three basic arguments to support this thesis. First, no ancient writer mentions such a union. Second, marriage to a widow, a divorced woman, or a prostitute disqualified a man from serving as high priest. Yet, Salome Alexandra’s husband Alexander and her sons Hyrcanus II and Aristobulus II were both high priests and kings. Third, Hyrcanus II, her eldest son, is always called the son of Salome Alexandra and Alexander Jannaeus. If Salome Alexandra had entered into a levirate marriage, he would have been referred to as the son of Judah Aristobulus and Salome Alexandra. | |||

==Select Bibliography (articles)== | |||

*'''Queen Salome and King Jannaeus Alexander: A Chapter in the History of the Second Jewish Commonwealth''' / [[Solomon Zeitlin]] / In: [[Jewish Quarterly Review]] 51 (1960-61) 1-33. | |||

*'''Queen Salamzion Alexandra and Judas Aristobulus I's Widow. Did Jannaeus Alexander Contract a Levirate Marriage?''' / [[Tal Ilan]] / In: [[Journal for the Study of Judaism]] 24 (1993) 181-190 | |||

*'''The Book of Judith, Queen Sholomzion and King Tigranes of Armenia: A Sadducee Appraisal''' / [[Samuel Rocca]] / In: [[Materia Giudaica]] 10.1 (2005) 1-14 | |||

*'''The Salome No One Knows: Long-Time Ruler of a Prosperous and Peaceful Judea Mentioned in Dead Sea Scrolls''' / [[Kenneth Atkinson]] / In: [[Biblical Archaeology Review]] 34 (2008) 60-65, 72-3. | |||

*'''Tigranes the Great as 'Nebuchadnezzar' in the Book of Judith''' / Gabriele Boccaccini / In: [[A Pious Seductress: Studies in the Book of Judith (2012 Xeravits), edited volume]], 55-69. | |||

}} | }} | ||

|} | |} | ||

|<!-- SPAZI TRA LE COLONNE --> style="border:5px solid transparent;" | | |<!-- SPAZI TRA LE COLONNE --> style="border:5px solid transparent;" | | ||

| Line 104: | Line 137: | ||

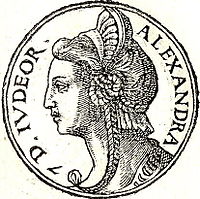

[[File:Salome Alexandra Rouille.jpg|thumb|left|250px|Salome Alexandra (1553), by [[Guillaume Rouille]]]] | |||

[[File:Salome Alexandra Street.jpg|thumb|left|250px|Salome Alexandra Street in Jerusalem]] | [[File:Salome Alexandra Street.jpg|thumb|left|250px|Salome Alexandra Street in Jerusalem]] | ||

|} | |} | ||

|} | |} | ||

Latest revision as of 14:49, 25 November 2019

|

Salome Alexandra -- Overview Salome Alexandra became Judea’s political ruler in 76 B.C.E. upon the death of her husband, Alexander Jannaeus, during the battle of Ragaba. Josephus hints that she actually held some political power during her husband’s twenty-seven year reign. He suggests this when he states that Antipas, the grandfather of Herod the Great, came to political power when “king Alexander and his wife made him general of all Idumea.” Salome Alexandra appointed her eldest son, John Hyrcanus II, as high priest. Her younger son, Aristobulus II, commanded her army. Salome Alexandra’s reign is regarded as the pinnacle of Pharisaic power. Josephus reports that she restored the Pharisaic regulations that her father-in-law, John Hyrcanus, had abolished. She was highly regarded for her piety. Her son, Aristobulus II, opposed her support of the Pharisees, and tried to remove her from power just before her death. Although Josephus claims that she was largely a pawn of the Pharisees, the prosperity of her reign, her military expansion, and her ability to bring peace between opposing religious factions, suggests that she was a strong and competent ruler. Josephus even acknowledges that Salome Alexandra was a wonderful administrator and that her reign was largely peaceful and prosperous. Salome Alexandra ruled during the disintegration of the Seleucid kingdom. Josephus suggests that she spent considerable money doubling the size of Judea’s army, and hired a core of mercenaries. Salome Alexandra conducted two major military campaigns. Both occurred as a result incursions into the region by Tigranes the Great. The first was an expedition against the Iturean Ptolemy, the son of Mennaeus, to prevent him from taking Damascus. Her son Aristobulus II commanded the Judean army. Josephus states that he returned home having accomplished nothing noteworthy. The extant historical sources and numismatic evidence suggest that we do not have a complete understanding of what occurred during this expedition. Tigranes minted coins in Damascus from 72/1 B.C.E. to 70/69 B.C.E. A coin of Cleopatra Selene and her son Antiochus XIII Asiaticus suggest that she held Damascus until 72/1 B.C.E. Prior to this time, the Nabatean king Aretas III occupied the city from 84/3 B.C.E. until 72 B. It is uncertain whether Aretas III or Cleopatra Selene was in possession of Damascus when Aristoublus II arrived. The Qumran text 4QHistorical Text D (4Q332) may contain an allusion to this time. Fragment two of this poorly preserved document contains an enigmatic passage that reads “[to] give him honor among the Arab[s .” This may refer to the campaign of Aristobulus II to Damascus, or perhaps to some unknown treaty Salome Alexandra made with Ptolemy or Aretas III. Line four of this text may refer to negotiations between one or more of these rulers and Salome Alexandra and reads: “with secret counsel Shelamzion came.” Salome Alexandra’s second campaign was in reaction to Tigranes’s invasion of Syria and Judea. He had apparently taken some Jews captive before besieging Cleopatra Selene in Ptolemais. The historical sources report that Salome Alexandra won over Tigranes by treaties and presents while he was attacking the city. Tigranes left the region shortly after capturing Ptolemais. He took Cleopatra Selene prisoner. Although Salome Alexandra may have convinced Tigranes to leave Syria, the sources suggest that an invasion of Armenia by the Roman general Lucullus gave him no option but to curtail his Syrian campaign and not attack Judea. Salome Alexandra’s reign appears to have been peaceful following Tigranes’s departure. She became ill during her final days and tried to ward off a coup by her youngest son. Sometime before her death she appointed Hyrcanus II her successor. She died in 67 BCE, at the age of seventy-three. She ruled Judea for nine years. The Talmud and other Jewish writings contain favorable references to her reign, and consider it a golden age.

Salome Alexandra in literature & the arts The Israeli author, playwright, and politician, Moshe Shamir (1921-2004) includes Salome Alexandra in his 1958 novel The King of Flesh and Blood, which is a fictional account of a portion of Alexander Jannaeus’s reign. The contemporary playwright Lauri Donahue has written a 2003 play focusing on Salome Alexandra titled “Alexandra of Judea.” Popular Culture Following the creation of the modern State of Israel, Jerusalem’s authorities changed the name of Princess Mary Street to Queen Shlomzion Street to honor Salome Alexandra. In 1977, Ariel Sharon, the former Israeli politician, general, and prime minster, named his now-defunct political party, Shlomtzion (“Peace of Zion”). References

Related categories External links

History of research Azariah de' Rossi (16th century Jewish-Italian Writer) is one the first interpreters of Salome Alexandra. He writes: "It is stated that of the Hasmoneans, Johanan the first, also Hyrcanus, was the father of Jannaeus Alexander, the husband of Queen Alexandra. On his deathbed, he advised her to transfer her allegiance from the Sadducees to the Pharisees who would be supportive of her rule. … It would seem that it is to these stories about the man and his wife, which the sages’ statement in tractate Sota refer: “Jannai the king said to his wife, ‘Do not fear the Pharisees or the non-Pharisees, but rather the hypocrites.’” (Joanna Weinberg, trans. The Light of the Eyes [Yale University Press, 2001). In 1892 rabbi Henry Zirndorf devoted to the Queen a chapter of his book on “Some Jewish Women.” In 1972 Solomon Zeitlin emphasized the many similarities between the fictional character of Judith and Salome Alexandra. Zeitlin however did not see any major political event in the life of Alexandra that could have prompted such a connection. The revised edition of Schurer in 1973 also reiterated the view that "no political events of any importance occurred during her reign." In 2005 Samuel Rocca first suggested that the story of Judith could contains echoes of the crisis generated by the invasion of the Armenian King Tigranes the Great. The argument was taken up in 2009 by Gabriele Boccaccini who drew attention on the Armenian and Roman sources that seem to confirm the chronological and geographical details provided in the Book of Judith about the military campaign of the new "Nebuchadnezzar," Tigranes the Great. Tal Ilan has recently published a book that examines rabbinic accounts of Salome Alexandra, and the various spellings of her name in antiquity. Ernst Axel Knauf has recently proposed that Salome Alexandra’s reign is reflected in canonical Psalms 148 and 2, and that the latter contains an acrostic that mentions her and her husband. The name Until the discovery of the Dead Sea Scrolls Salome Alexandra’s exact name was the subject of a scholarly debate. In Jewish literature she is referred to as Shel-Zion, Shalmonin, Shalmza, Shlamto, and similar names. This confusion led Jacob Neusner to comment that Salome Alexandra is “…a queen whose name no one can get straight.” In 1899 the French scholar Charles Clermont-Ganneau, proposed that Shelamzion is her Semitic name. The Dead Sea Scrolls now confirm his proposal and mention her twice by this name. Salina or Salome Alexandra? According to Josephus, Salome Alexandra’s husband, Alexander Jananeus, came to the throne under unusual circumstances. He writes of this transition: Salina, called Alexandra by the Greeks, released Judah Aristobulus’s brothers—for Aristobulus had imprisoned them, as we have said before—and appointed as king Jannaeus, also known as Alexander, who was best fitted for this office by reason of his age and because he knew his place. (Ant. 13.320-1; cf. War 1.85) Most scholarship on this period accepts the thesis that Salina Alexandra is Salome Alexandra. According to this interpretation she appointed her brother-in-law, Alexander Jannaeus, as king and high priest. She then married him in accordance with the rules of levirate marriage found in Deuteronomy 25. Kenneth Atkinson and Tal Ilan have recently argued that Salina Alexandra is the wife of Salome Alexandra’s brother-in-law, Judah Aristobulus. According to this theory, Salome Alexandra never contracted a levirate marriage with Alexander Jannaeus. The two propose three basic arguments to support this thesis. First, no ancient writer mentions such a union. Second, marriage to a widow, a divorced woman, or a prostitute disqualified a man from serving as high priest. Yet, Salome Alexandra’s husband Alexander and her sons Hyrcanus II and Aristobulus II were both high priests and kings. Third, Hyrcanus II, her eldest son, is always called the son of Salome Alexandra and Alexander Jannaeus. If Salome Alexandra had entered into a levirate marriage, he would have been referred to as the son of Judah Aristobulus and Salome Alexandra. Select Bibliography (articles)

|

Highlights

Salome Alexandra (1553), by Guillaume Rouille |

Pages in category "Salome Alexandra (subject)"

The following 11 pages are in this category, out of 11 total.

1

2

- Alexandra of Judea (2003 Donahue), play

- Silencing the Queen (2006 Ilan), book

- Alexandra Salomé: a rainha dos judeus (Salome Alexandra: Queen of the Jews (2011 Portoliveira), novel

- Queen Salome: Jerusalem’s Warrior Monarch of the First Century B.C.E. (2012 Atkinson), book

- Queen of the Jews: Salome Alexandra (2012 Petsonk), novel

- Jerusalem's Queen: A Novel of Salome Alexandra (2018 Hunt), novel

Media in category "Salome Alexandra (subject)"

This category contains only the following file.

- 2012-E Xeravits.jpg 339 × 499; 18 KB