Difference between revisions of "Category:Letter of Barnabas (text)"

| (19 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

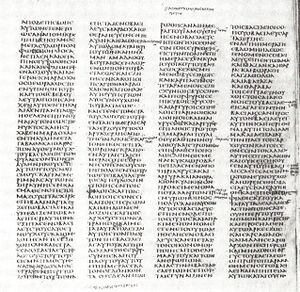

[[File:Epistle Barnabas.jpg|thumb|300px|Codex Sinaiticus]] | |||

*[[:Category:Texts|BACK TO THE TEXTS--INDEX]] | *[[:Category:Texts|BACK TO THE TEXTS--INDEX]] | ||

The '''Letter of Barnabas''' is an early Christian document, included in collections of [[Apostolic Fathers]]. | The '''Letter of Barnabas''' is an early Christian document, included in collections of [[Apostolic Fathers]]. | ||

* See [http://www.earlychristianwritings.com/text/barnabas-roberts.html Online Text] | * See [http://www.earlychristianwritings.com/text/barnabas-roberts.html Online Text] | ||

== Date and Authorship == | |||

In 16.3–4, the Epistle of Barnabas reads: | |||

:Furthermore he says again, "Behold, those who tore down this temple will themselves build it." It is happening. For because of their fighting it was torn down by the enemies. And now the very servants of the enemies will themselves rebuild it. | |||

This passage places the Epistle after the destruction of the Second Temple in the year 70 CE. It also places the Epistle before the Bar Kochba Revolt of 132 CE, after which there could have been no hope that the Romans would help to rebuild the temple. The document must therefore come from the period between the two Jewish revolts (end of the first century, beginning of the second century CE). | |||

The Epistle is traditionally attributed to [[Barnabas]], the leader of the Christian community at Antioch, Syria, who is mentioned in the Acts of the Apostles. However, the late date of composition and the possible Egyptian setting of the Letter, however, make it very unlikely. According to tradition, Barnabas died in the 60s. The Epistle is now generally attributed to an otherwise unknown early Christian teacher, perhaps of the same name, who lived in Egypt at the end of the first century, beginning of the second. | |||

==Major topics in the Letter== | ==Major topics in the Letter== | ||

[[File:Bible Code Sun.jpg|thumb|right| | [[File:Bible Code Sun.jpg|thumb|right|200px]] | ||

=====Gematria===== | |||

In Greek, each letter possesses a numerical value. "Gematria" is the art of calculating the numerical equivalence of letters, words, or phrases. In antiquity it was a popular method of interpreting sacred texts. In the Hebrew Scripture there is no reference to Jesus. The author of the letter applied gematria to a biblical text, turning the ancient narrative into a prophecy for Christ. | |||

:''Abraham, the first to perform circumcision was looking ahead in the Spirit to Jesus when he circumcised. For he received the firm teachings of the three letters. For it says: Abraham circumcised eighteen and three hundred men from his household [Gen 14:14; 17:23]… Notice that first he mentions the eighteen and then, after a pause, the three hundred. The number eighteen [in Greek] consists of an Iota [J], ten, and an Eta [E], eight. There you have Jesus [JEsous]. And because the cross was about to have grace in the letter Tau [T], he next gives the three hundred, Tau. And so he shows the name Jesus by the first two letters and the cross by the other'' (Barnabas 9:6-8). | |||

See [[Bible Code]] | See [[Bible Code]] | ||

| Line 16: | Line 31: | ||

=====Allegorical reading vs. literary reading===== | =====Allegorical reading vs. literary reading===== | ||

The allegorical interpretation of the Bible was common among Hellenistic Jews (see [[Letter of Aristeas]], [[Philo of Alexandria]]). The Letter of Barnabas now claims that the allegorical interpretation makes the Mosaic Torah obsolete. Those who understand the "true" meaning of Scripture (i.e. the Christians) do no longer need to obey the letter of the Law. | [[File:Good Shepherd.png|thumb|left|200px]] | ||

"Allegory" was another popular method of interpreting sacred texts in antiquity. Events and figures of ancient narratives were understood as metaphors and symbols for moral teaching, as if they were parables. | |||

The allegorical interpretation of the Bible was common among Hellenistic Jews (see [[Letter of Aristeas]], [[Philo of Alexandria]]). ''"The good life consists in observing the laws and this aims is achieved by hearing much more than by reading… In the matter of meat, the unclean reptiles, the beasts, the whole underlying rationale is directed toward righteousness and right human relationships."'' (Letter of Aristeas). Hellenistic Jews however maintained that the literary meaning was still valid. The biblical laws have an allegorical meaning but must be observed as God’s perfect ''paideia'' (education) | |||

The Letter of Barnabas now claims that the allegorical interpretation makes the Mosaic Torah obsolete. Those who understand the "true" meaning of Scripture (i.e. the Christians) do no longer need to obey the letter of the Law. In contrast, those who still follow the Law (i.e. the other Jews) are denounced as being attached to an inferior form of knowledge. | |||

: | :''The commandment of God is not a matter of avoiding food; but Moses spoke in the spirit. This is why he spoke about the pig: Do not cling – he says – to such people, who are like pigs… who live in luxury and forget the Lord, but when they are in need they remember the Lord. This is just like the pig: when it is eating, it does not know its master, but when hungry, it cries out… Do not eat the hare… You must not be one who corrupts children or be like such people. For the rabbit adds an orifice every year; it has as many holes as years it has lived… Moses received teachings about food and spoke in the spirit. But they [the Jews] received his words according to the desires of their own flesh, as if he were actually speaking about food…'' (Barnabas 10:1-9). | ||

[[File:Blind Synagogue1.jpg|thumb|right|200px]] | |||

=====Christianity vs. Judaism ===== | =====Christianity vs. Judaism ===== | ||

Some people are wrong “saying that the covenant is both theirs and ours. For it is ours. They (the Jews) permanently lost it…Their covenant was smashed—that the covenant of his beloved, Jesus, might be sealed in our hearts, in the hope brought by faith in him” (4:6-7,10). “They violated [God’s] Law, because an evil angel instructed them...” (9:4). | Christianity was born as a Jewish messianic movement and the first Christians looked at themselves as "Jews." There was some tension between Jews and gentiles within the new movement, and the Christian leaders, like Paul, had to intervene to remind their followers that Christianity was "Israel": | ||

:“Has God rejected his people? By no means!… God has not rejected his people whom he foreknew…If some of the branches were broken off, and you, a wild olive shoot, were grafted in their place to share the rich root of the olive tree, do not boast over the branches… Remember that it is not you that support the root, but the root that supports you” (Rom 11) | |||

After the destruction of the Jerusalem Temple the relation of Christianity with the other Jewish groups became more and more difficult. Christians were divided; some, like the author of the [[Gospel of Matthew]] saw the future of Christianity within Judaism, others pushed for a radical schism: | |||

:''Some people are wrong “saying that the covenant is both theirs and ours. For it is ours. They (the Jews) permanently lost it…Their covenant was smashed—that the covenant of his beloved, Jesus, might be sealed in our hearts, in the hope brought by faith in him” (4:6-7,10). “They violated [God’s] Law, because an evil angel instructed them...”'' (9:4). | |||

See [[Antisemitism]] | See [[Antisemitism]] | ||

Latest revision as of 08:46, 25 March 2021

The Letter of Barnabas is an early Christian document, included in collections of Apostolic Fathers.

- See Online Text

Date and Authorship

In 16.3–4, the Epistle of Barnabas reads:

- Furthermore he says again, "Behold, those who tore down this temple will themselves build it." It is happening. For because of their fighting it was torn down by the enemies. And now the very servants of the enemies will themselves rebuild it.

This passage places the Epistle after the destruction of the Second Temple in the year 70 CE. It also places the Epistle before the Bar Kochba Revolt of 132 CE, after which there could have been no hope that the Romans would help to rebuild the temple. The document must therefore come from the period between the two Jewish revolts (end of the first century, beginning of the second century CE).

The Epistle is traditionally attributed to Barnabas, the leader of the Christian community at Antioch, Syria, who is mentioned in the Acts of the Apostles. However, the late date of composition and the possible Egyptian setting of the Letter, however, make it very unlikely. According to tradition, Barnabas died in the 60s. The Epistle is now generally attributed to an otherwise unknown early Christian teacher, perhaps of the same name, who lived in Egypt at the end of the first century, beginning of the second.

Major topics in the Letter

Gematria

In Greek, each letter possesses a numerical value. "Gematria" is the art of calculating the numerical equivalence of letters, words, or phrases. In antiquity it was a popular method of interpreting sacred texts. In the Hebrew Scripture there is no reference to Jesus. The author of the letter applied gematria to a biblical text, turning the ancient narrative into a prophecy for Christ.

- Abraham, the first to perform circumcision was looking ahead in the Spirit to Jesus when he circumcised. For he received the firm teachings of the three letters. For it says: Abraham circumcised eighteen and three hundred men from his household [Gen 14:14; 17:23]… Notice that first he mentions the eighteen and then, after a pause, the three hundred. The number eighteen [in Greek] consists of an Iota [J], ten, and an Eta [E], eight. There you have Jesus [JEsous]. And because the cross was about to have grace in the letter Tau [T], he next gives the three hundred, Tau. And so he shows the name Jesus by the first two letters and the cross by the other (Barnabas 9:6-8).

See Bible Code

Allegorical reading vs. literary reading

"Allegory" was another popular method of interpreting sacred texts in antiquity. Events and figures of ancient narratives were understood as metaphors and symbols for moral teaching, as if they were parables.

The allegorical interpretation of the Bible was common among Hellenistic Jews (see Letter of Aristeas, Philo of Alexandria). "The good life consists in observing the laws and this aims is achieved by hearing much more than by reading… In the matter of meat, the unclean reptiles, the beasts, the whole underlying rationale is directed toward righteousness and right human relationships." (Letter of Aristeas). Hellenistic Jews however maintained that the literary meaning was still valid. The biblical laws have an allegorical meaning but must be observed as God’s perfect paideia (education)

The Letter of Barnabas now claims that the allegorical interpretation makes the Mosaic Torah obsolete. Those who understand the "true" meaning of Scripture (i.e. the Christians) do no longer need to obey the letter of the Law. In contrast, those who still follow the Law (i.e. the other Jews) are denounced as being attached to an inferior form of knowledge.

- The commandment of God is not a matter of avoiding food; but Moses spoke in the spirit. This is why he spoke about the pig: Do not cling – he says – to such people, who are like pigs… who live in luxury and forget the Lord, but when they are in need they remember the Lord. This is just like the pig: when it is eating, it does not know its master, but when hungry, it cries out… Do not eat the hare… You must not be one who corrupts children or be like such people. For the rabbit adds an orifice every year; it has as many holes as years it has lived… Moses received teachings about food and spoke in the spirit. But they [the Jews] received his words according to the desires of their own flesh, as if he were actually speaking about food… (Barnabas 10:1-9).

Christianity vs. Judaism

Christianity was born as a Jewish messianic movement and the first Christians looked at themselves as "Jews." There was some tension between Jews and gentiles within the new movement, and the Christian leaders, like Paul, had to intervene to remind their followers that Christianity was "Israel":

- “Has God rejected his people? By no means!… God has not rejected his people whom he foreknew…If some of the branches were broken off, and you, a wild olive shoot, were grafted in their place to share the rich root of the olive tree, do not boast over the branches… Remember that it is not you that support the root, but the root that supports you” (Rom 11)

After the destruction of the Jerusalem Temple the relation of Christianity with the other Jewish groups became more and more difficult. Christians were divided; some, like the author of the Gospel of Matthew saw the future of Christianity within Judaism, others pushed for a radical schism:

- Some people are wrong “saying that the covenant is both theirs and ours. For it is ours. They (the Jews) permanently lost it…Their covenant was smashed—that the covenant of his beloved, Jesus, might be sealed in our hearts, in the hope brought by faith in him” (4:6-7,10). “They violated [God’s] Law, because an evil angel instructed them...” (9:4).

See Antisemitism

External links

- Wikipedia --

Pages in category "Letter of Barnabas (text)"

The following 13 pages are in this category, out of 13 total.

1

- The Famous Epistles of Saint Polycarp and Saint Ignatius... with the Epistle of St. Barnabas (1668 Elborow), book

- Sancti Barnabæ Apostoli Epistola Catholica (1685 Fell, Bernard), book

- Barnabae Epistula (1866 Hilgenfeld), book

- A Dissertation on the Epistle of S. Barnabas (1877 Cunningham), book

- De brief van Barnabas (1901 Veldhuizen), book

- Der Einfluss Philos auf die älteste christliche Exegese (Barnabas, Justin und Clemens von Alexandria) (1908 Heinisch), book

- Barnabas, Hermas and the Didache (1920 Robinson), book

- Barnabas and the Didache (1965 Kraft), book

- Épître de Barnabé (1971 Kraft & Prigent), book

- The Epistle of Barnabas: Outlook and Background (1994 Paget), book

- The Struggle for Scripture and Covenant: The Epistle of Barnabas and Jewish-Christian Competition in the Second Century (1996 Hvalvik), book

Media in category "Letter of Barnabas (text)"

The following 3 files are in this category, out of 3 total.

- 1912 * Lake.jpg 304 × 475; 28 KB

- 1964-E * Grant.jpg 907 × 1,360; 189 KB

- 2003 * Ehrman 3.jpg 947 × 1,417; 189 KB