George & Hana Brady (MF / Czechia, 1928-2019, 1931-1944), Holocaust survivor & victim

George Brady / Jiří Brady (M / Czechia, 1928-2019), Holocaust survivor

- One of the collaborators of the magazine Vedem.

- KEYWORDS : <Theresienstadt> <Auschwitz> <Death March> -- <Canada>

Hana Brady / Hanička Bradyová (F / Czechia, 1931-1944), Holocaust victim

- KEYWORDS : <Theresienstadt> <Auschwitz>

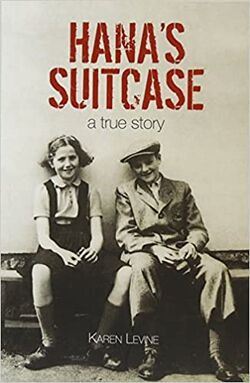

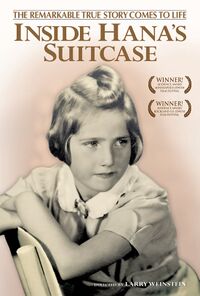

- MEMOIRS : see Hana's Suitcase (2002), by Karen Levine -- Inside Hana's Suitcase (doc, 2009), by Larry Weinstein

Biography

- <Wikipedia.en>

George and Hana were the children of Markéta and Karel. They lived an ordinary childhood in interwar Czechoslovakia until March 1939, when Nazi Germany took control of Bohemia and Moravia. After that, their Jewish family encountered increasing restrictions and persecution by the German occupiers. By 1942, the parents had been separated from their children and sent to prisons and Nazi concentration camps, perishing in Auschwitz before the end of the Second World War. For a short time, George and Hana stayed with an aunt and uncle; he was not Jewish, and thus the couple was a "privileged" mixed marriage and not subject to deportation. The children were deported in May 1942 to Theresienstadt, where George shared Kinderheim L417 with around forty boys including Petr Ginz, Yehuda Bacon, and Kurt Kotouc.

George and Hana remained in Theresienstadt until 1944, when they were sent in separate convoys to Auschwitz — George in September to the work camp and Hana in October, where she was soon executed in a gas chamber. George was transferred from Auschwitz to Gleiwitz I subcamp, where he worked repairing damaged railway cars. Brady escaped during a death march to Germany in January 1945, the same month Auschwitz was liberated.

Brady traveled until May 1946 when he reached his aunt and uncle in Nové Město or Czechoslovakia and he learned from them that his parents had died in Auschwitz. After the Communist coup in 1948, he escaped to Austria in 1949 and moved to Toronto, Ontario, Canada, two years later, where he became a successful businessman.

The story of George and his sister Hana (who perished in the Holocaust, 1931-1944) was featured in 2002 in the book Hana's Suitcase, written by Karen Levine. It became a documentary in 2009.

Book : Hana's Suitcase (2002), by Karen Levine

The story of Hana Brady first became public when Fumiko Ishioka (石岡史子, Ishioka Fumiko), a Japanese educator and director of the Japanese non-profit Tokyo Holocaust Education Resource Center, exhibited Hana's suitcase in 2000 as a relic of the concentration camp.

Visiting Auschwitz in 1999, Ishioka requested a loan of children's items, things that would convey the story of the Holocaust to other children. The suitcase turned out to be a very capable means of telling the story of the Holocaust, reaching out to children at their level.

The suitcase (a replica of the original destroyed in an arson in 1984) has large writing on it, a name and birthdate and the German word, Waisenkind (orphan). Ishioka began painstakingly researching Hana's life and eventually found her surviving brother George in Canada.

The story of Hana Brady and how her suitcase led Ishioka to Toronto became the subject of a CBC documentary. Karen M. Levine (born 1955), the producer of that documentary, was urged to turn the story into a book by a friend who was a publisher and whose parents were Holocaust survivors.

The 2002 book became a bestseller and received the Bank Street College of Education Flora Stieglitz Straus Award for non-fiction, the National Jewish Book Award, and several other Canadian awards for children's literature. The book received a nomination for the Governor General's Award and was selected as a final award candidate for the Norma Fleck award. It has been translated into over 20 languages and published around the world. In October 2006, the book won the Yad Vashem award, presented to George Brady at a ceremony in Jerusalem.

Doc : Inside Hana's Suitcase (2009), by Larry Weinstein

""Inside Hana's Suitcase", is the poignant story of two young children who grew up in pre-WWII Czechoslovakia and the terrible events that they endured just because they happened to be born Jewish. Based on the internationally acclaimed book "Hana's Suitcase" which has been translated into 40 languages, the film is an effective blend of documentary and dramatic techniques. In addition to tracing the lives of George and Hana Brady in the 1930's and 40's, "Inside Hana's Suitcase" tells the present-day story of "The Small Wings", a group of Japanese children, and how their passionate and tenacious teacher, Fumiko Ishioka, helped them solve the mystery of Hana Brady, whose name was painted on an old battered suitcase that they received from Auschwitz, the notorious Nazi death camp built in Poland. The film's plot unfolds as told through contemporary young storytellers who act as the omniscient narrators. They seamlessly transport us through 70 years of history and back and forth across three continents, and relate to us a story of unspeakable sadness and also of shining hope. For this is a Holocaust story unlike others. It provides a contemporary global perspective and lessons to be learned for a better future. Directed by award-winning filmmaker, Larry Weinstein, "Inside Hana's Suitcase" is a powerful journey full of mystery and memories, brought to life through the first-hand perspectives of Fumiko, Hana's brother George, and of Hana herself."

Yad Vashem

Hana’s Suitcase seems, at first glance, to be a book written for children. On the cover is a beautiful sepia-toned portrait of a little girl with a faraway look in her eyes and a slight smile. She is wearing a pressed dress with a ruffled white collar and a broach; her shiny hair is twisted and pinned up, and reflects the light. This lovely little girl in the photographic portrait ordered, no doubt, by her doting parents, could be any beloved little girl, anywhere.

The title of the book and the author’s name appear on the cover in a typeface that could have been scrawled by a child. The book’s print is large, and its sentences are short and simple. In the Introduction, World War II, Adolf Hitler, and concentration camps are explained briefly, for those not familiar with the terms.

Surely, then, this must be a book for children. But that’s just the point – though Hana’s Suitcase is a wonderful story about how the director of a museum in Tokyo, Japan, together with a handful of Japanese children, solved a mystery related to one Jewish child who perished in the Holocaust, the book is hardly just a children’s book. It is also an incredible story about persistence, and about how important it is to put faces and names and life stories to each of the millions of victims of the Holocaust. It was only through persistence and stubbornness and refusing to give up that Fumiko Ishioka and her Japanese schoolchildren rediscovered Hana Brady and brought her back to life.

The book about their search, about Hana, and about the Japanese children who “found” her, is much more than just a children’s book, though it engages the young reader as well. It is filled with pictures of Hana playing in the snow, acting in costume for a school play, sitting in the sun with her brother, posing with a doll that is almost bigger than she is. It keeps the young reader interested by jumping back and forth in time and in place – from Tokyo in 2000, to Czechoslovakia in the 1930s, and back to Tokyo again. It unravels the story of Hana’s suitcase as though it is a true detective story – with clues, dead ends, twists and turns.

But again – it is much more than a children’s story. Hana’s Suitcase is the story of a very short life – the life of one child – that was rediscovered, dusted off, and reexamined. In this, it has a great deal of value for adults as well.

Children in the Holocaust Children were particularly vulnerable during the Holocaust. Deemed a threat to future Aryan domination, and too young to be of use to the Nazi war machine as slave labor, children were killed en masse. The Germans and their collaborators murdered more than one and one-half million Jewish children during the Holocaust. For those who remained alive, the ruthlessness of Nazi rule and the barbarities of war forced many to mature beyond their years. Many children took on responsibilities that are normally associated with adults, such as providing food for, or working to support, their families. They were forced to become the breadwinners when their parents were unable to properly care for them. They made difficult choices that often affected the future of their families, such as the decision to smuggle food, which could result in death. Often, they had to struggle to live without any parental supervision at all. These are subjects often overlooked when teaching the Holocaust.

Why Teach About Children During the Holocaust? Teaching about children during the Holocaust allows younger students to learn and empathize with people roughly their age, at a stage of life to which they can relate. Almost anything that is true of adults during the Holocaust was true of children as well – they, too, went into hiding; they, too, were forced to move into ghettos; they, too, were shipped in cattlecars to death camps; they, too, were humiliated, terrified, broken and somehow still hopeful; they, too, were sent to their deaths.

Sometimes teaching the stories of children – the stories of victims of the Holocaust who were young and vulnerable, and to whom children can relate – can provide teachers with a new approach.

Hana’s Suitcase Hana’s Suitcase exemplifies this. Yad Vashem’s pedagogical philosophy holds that the victims of the Holocaust cannot and should not be seen as six million nameless, faceless victims; identifying the victims and giving them back their names and faces makes them more accessible, since we are then able to realize that each victim was a person made of flesh and blood, with parents, siblings, hopes, dreams and an entire universe, just as we are.

This is what Hana’s Suitcase does.

The story begins at a tiny Holocaust museum in Tokyo, the Tokyo Holocaust Education Resource Center. The Center, which was endowed by an anonymous Japanese donor, is dedicated to contributing to global tolerance and understanding. Little did this donor know that his Center, and the mystery its director unraveled, would – like a pebble cast into a lake – create ripples far and wide across the world.1

When the director of the Tokyo Holocaust Education Resource Center, Fumiko Ishioka, asks the museum at Auschwitz for an artifact that will help children connect with the Holocaust, she receives a suitcase that had belonged to one of Auschwitz’s victims. Written on the brown, slightly battered suitcase, in white paint, is a girl’s name: “Hanna Brady,”2 her date of birth, May 16, 1931, and the word “Waisenkind,” German for “orphan.” Fumiko and a group of children who volunteer at the Center become very curious about the suitcase’s owner. Who was she? Where did she come from? How did she become an orphan? What happened to her? The empty suitcase provides no clues. The children implore Fumiko to find out all she can about the girl who owned the suitcase – the only Holocaust artifact that the Center has that is actually linked to a name. The children figure out that Hana Brady would have been about thirteen years old – close to their own ages – when she was sent to Auschwitz.

To find out more about Hana, Fumiko delves into the past, looking for clues. After her initial inquiries come up with dead ends, a list is discovered that shows Hana came to Auschwitz from the ghetto of Theresienstadt, in Czechoslovakia.

From the minute she learns about Theresienstadt, Fumiko’s journey to “find” Hana takes on surprising twists that are reflected in the book. But while the book chronicles Fumiko’s persistence and her search for information about Hana, it also goes back in time to explore Hana’s life with her family in Czechoslovakia in the 1930s. We learn about the increasing restrictions on the Jews after Czechoslovakia is invaded by the German army in March, 1939; about Hana’s frustration when she is forbidden to attend third grade because she is Jewish; about Hana’s mother’s arrest by the Gestapo and her imprisonment at Ravensbrück concentration camp in Germany. We understand Hana’s humiliation when she is forced to wear the yellow star, and her shock and terror when her father, too, is picked up by the Gestapo and she and her brother, George, are left alone. Hana and George are taken in by their father’s sister, and her husband, a Christian – but even they are unable to protect the children for long – in May of 1942, both children are deported. We envision Hana and George, alone in the world, celebrating Hana’s 11th birthday in a crowded, dirty warehouse on May 16, 1942 with hundreds of other Jews waiting to be sent to Theresienstadt; we imagine her horror and fear as, upon reaching Theresienstadt, she is separated from her brother, the only person she has left in the world, and assigned to a barrack for girls at Theresienstadt. We learn that Hana loved to draw, that she created pictures of picnics and open fields while she was in Theresienstadt, in the art classes she had with Friedl Dicker-Brandeis, but that she also drew pictures of trains like the one that had taken her away from her aunt and uncle. We learn other things about Hana, as well – that George tried to protect her at Theresienstadt; that Hana was devoted to her big brother and gave him the doughnut she received every week instead of eating it herself; that their elegant and cultured grandmother, who arrived in Theresienstadt from Prague was housed in a stifling, filthy attic and was dead within three months; that Hana was heartbroken when George’s name was on a list in September, 1944 and he was shipped to the east. Perhaps the saddest of all, we learn that four weeks later, when Hana found out that her name was on a list and that she, too, was being shipped “to the east,” she washed her face and did her hair specially with the help of a friend so that she would look nice when she was reunited with George. Hana arrived at Auschwitz on October 23, 1944 and was sent directly to the gas chambers.

Fumiko’s sleuthing ultimately leads to a boy that had shared a bunk with Hana’s brother, George, in Theresienstadt, who knew that George had survived Auschwitz and was living in Canada. This part of the story is particularly miraculous. George is stunned when he receives a package from Tokyo with inquiries from the Center, and is willing to reopen, at age 72, a chapter of his life that he had closed long ago in order to help Fumiko discover who Hana was and what her short life had been like.

This slim book with its simple sentences that children can understand has a story that is universal in its appeal; in telling the story, it brings one small face – a little girl with a faraway look in her eyes and a slight smile – into sharp focus. It turns one more victim of the Holocaust into a flesh-and-blood human being that adults and children can relate to.