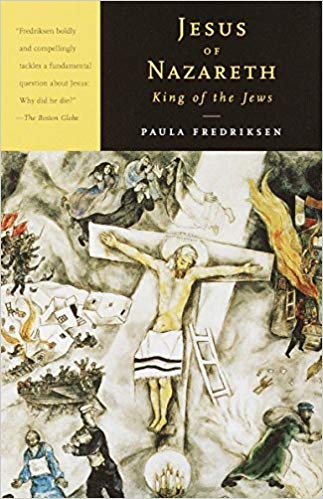

File:1999 * Fredriksen.jpg

1999_*_Fredriksen.jpg (323 × 499 pixels, file size: 41 KB, MIME type: image/jpeg)

Jesus of Nazareth, King of the Jews: A Jewish Life and the Emergence of Christianity (1999) is a book by Paula Fredriksen.

Abstract

"Draws on the narratives of all four evangelists as well as both John and the Synoptics, the Dead Sea Scrolls, Jewish authorities of Jesus' time, Philo, Paul, and Josephus who wrote in Greek, and early rabbinic writings. She shows us a historical Jesus living in the tumultuous world of late-Second Temple Judaism; an observant Jew of his time, a prophetic teacher who traveled through the villages of Galilee and frequently in and around Jerusalem". -- Jacket.

Editions

Published in New York, NY: Knopf, 1999.

Contents

Introduction: The History of the Historical Jesus --; 1.; Gospel Truth and Historical Innocence --; 2.; God and Israel in Roman Antiquity --; 3.; Trajectories: Paul, the Gospels, and Jesus --; 4.; Contexts: The Galilee, Judea, and Jesus --; 5.; The Days in Jerusalem --; Afterword: Jesus, Christianity, and History.

Excerpts

“Here we have to retrieve one of our observable facts, that later tradition continues to attribute to Jesus an already disconfirmed prophecy; and one of our interpretive conjectures, that much of our scattered evidence can be coherently brought together by an appeal to broader Jewish apocalyptic tradition. To the New Testament evidence first. Moving backward along a trajectory from later text to earlier text to, finally, Jesus himself, we might hypothesize a gradient of increasing apocalyptic intensity. Matthew and Luke had Jesus proclaim the coming Kingdom, though they both defined ‘kingdom’ in nonapocalyptic as well as apocalyptic ways, and they linked the Kingdom to Jesus’ glorious Second Coming. In this they follow Mark, whose Jesus proclaimed the coming Kingdom, conceived apocalypticly: That is, the Kingdom was an event that would happen or a stage that would arrive, not a state that somehow existed concurrent with normal reality. This Kingdom would arrive within the lifetime of Mark’s generation, at the edges of the lifetime of Jesus’. And it would begin with the return of the triumphant Son. Mark’s tone of confident immediacy matches that of Paul, a generation earlier. Paul, too, had proclaimed the imminent return of the Son, the resurrection of the dead, and the establishment of the Kingdom within his own lifetime. Paul said that he inherited this tradition: He has it as a ‘saying of the Lord’ (1 Thes 4:13). Might not some version of this teaching go back through those who were apostles before Paul to the teaching of Jesus himself? Jesus’ messianic, triumphant appearance as the vindicated, militant Son most easily coheres, it is true, with post-Crucifixion developments. It compensates for the disappointment of Jesus’ crucifixion and clearly stands as a specifically Christian embellishment on earlier Jewish traditions of Messiah and Kingdom. But the Kingdom itself, the belief that it is coming, that it will particularly manifest in Jerusalem, that it will involve the restored nation of Israel as well as Gentiles who have renounced their idolatry—all these beliefs predate Jesus’ death by centuries and are also found variously in other Jewish writings roughly contemporary with him (some Pseudepigrapha; the Dead Sea Scrolls). Predicting his own Second Coming may indeed be historically implausible. Preaching the good news of the coming Kingdom of God, not at all.”

”The Jesus encountered in the present reconstruction is a prophet who preached the coming apocalyptic Kingdom of God. His message coheres both with that of his predecessor and mentor, John the Baptizer, and with that of the movement that sprang up in his name. This Jesus thus is not primarily a social reformer with a revolutionary message; nor is he a religious innovator radically redefining the traditional ideas and practices of his native religion. His urgent message had not the present so much as the near future in view. Further, what distinguished Jesus’ prophetic message from those of others was primarily its timetable, not its content. Like John the Baptizer, he emphasized his own authority to preach the coming Kingdom; like Theudas, the Egyptian, the signs prophets, and again like the Baptizer, he expected its arrival soon.”

”If modern believers seek a Jesus who is morally intelligible and religiously relevant, then it is to them that the necessary work of creative and responsible reinterpretation falls. Such a project is not historical (the critical construction of an ancient figure) but theological (the generation of contemporary meaning within particular religious communities). Multiple and conflicting theological claims inevitably result, as various as the different communities that stand behind them. But this theological reinterpretation should neither be mistaken for, nor presented as, historical description. To regard Jesus historically requires releasing him from service to modern concerns or confessional identity. It means respecting his integrity as an actual person, as subject to passionate conviction and unintended consequences, as surprised by turns of events and as innocent of the future as is anyone else. It means allowing him the irreducible otherness of his own antiquity, the strangeness Schweitzer captured in his poetic closing description: ‘He comes to us as One unknown, without a name, as of old, by the lakeside.’ It is when we renounce the false familiarity proffered by the dark angels of Relevance and Anachronism that we see Jesus, his contemporaries, and perhaps even ourselves, more clearly in our common humanity.”

External links

File history

Click on a date/time to view the file as it appeared at that time.

| Date/Time | Thumbnail | Dimensions | User | Comment | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| current | 15:27, 28 July 2018 |  | 323 × 499 (41 KB) | Gabriele Boccaccini (talk | contribs) |

You cannot overwrite this file.

File usage

The following page uses this file:

- File:1999 Fredriksen.jpg (file redirect)