Arek Herszlikowicz / Arek Hersh (M / Poland, 1928), Holocaust survivor

Arek Herszlikowicz / Arek Hersh (M / Poland, 1928), Holocaust survivor.

- KEYWORDS : <Auschwitz> <Buchenwald> <Death March> <Theresienstadt> / <Liberation of Theresienstadt / <England> <Windermere Children>

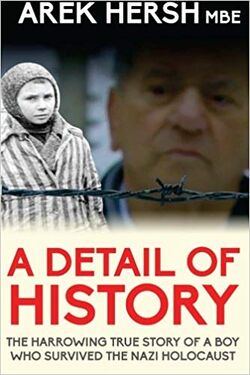

- MEMOIRS : A Detail of History (1998)

Biography

Arek Hersh (b.1928) was one of the very few Jewish survivors of his hometown, Sieradz, Poland. He was moved around several camps before being taken to Auschwitz. He was eventually liberated at Theresienstadt. Hersh was included in a group of 300 Holocaust-surviving children who, following their liberation, were brought to the Lake District in England as part of a rehabilitation plan. He has lived in England ever since.

Book : A Detail of History (1998)

- A Detail of History: The Harrowing True Story of a Boy Who Survived the Nazi Holocaust (Laxton: Beth Shalom, 1998). Repr. Malmesbury, UK: Apostrophe Books, 2015.

"How do you survive when you’re 11 years old and all your family have been taken from you and killed? How do you continue to live, when everything around you is designed to ensure certain death? Arek Hersh tells his story simply and honestly, a moving account of a little boy who made his own luck and survived. He takes us into the tragic world imposed on him that robbed him of his childhood. The depth of the tragedy, strength of courage and power of survival will move you and inspire you. Contrary to assertions that the Holocaust years were a mere ‘detail of history’, Arek Hersh gives us a glimpse into the greatest catastrophe that man has ever inflicted on his fellow man."--Publisher description.

Profile

NOTES : Before the war, Hersh – Herszlikowicz back then – lived with his parents, brother and three sisters in Sieradz, a garrison town in west Poland. His father was a bootmaker, much in demand for making officers’ footwear. When the Nazis invaded, they came first for Hersh’s father, but he escaped; they came back for his brother, but he also slipped away. That left 11-year-old Arek, who was packed off to a labour camp near Poznan to lay lines and sleepers for the Poznan-Warsaw railway, which would speed up the German attack on the Soviet Union. One of his responsibilities was to clean the room of the camp commandant, who every day would leave Hersh a hunk of bread on his desk. It wasn’t much, but Hersh believes it saved his life. “We started with 2,500 men,” he says. “Within 18 months, there were only 11 of us left alive. And I was one of them. Very, very lucky.”

When he was sent to Auschwitz in 1944, he told the SS officer that he was 17 and a locksmith. He wasn’t either of those things; he just wanted to suggest that he might be useful to the Nazis. “So that’s what I said, and they told me to go to the right side,” says Hersh. “And 180 children all went to the wrong side. And they were murdered.”

The most gruelling experience for Hersh personally, however, came in the early months of 1945, when he was evacuated first on foot, in the bitter cold, to the Buchenwald camp in Germany and finally to the concentration camp at Theresienstadt in Czechoslovakia on what he calls “the train of damnation”. “A whole month on open wagons without food,” says Hersh, shaking his head. “We ate grass. I ate the leather on my left shoe to keep going. I didn’t swallow but I chewed it.”

Hersh was in Theresienstadt, expecting any moment to be killed, when the camp was liberated by the Russian army on 8 May, 1945. He was moved on to Prague and it was here he was selected for the Committee for the Care of Children from Concentration Camps, which was set up by the British philanthropist Leonard Montefiore

For almost half a century, he spoke to no one about his Holocaust experience. Not to his three daughters, who are old enough now not only to have kids of their own but also grandchildren. Nor to Jean, his second wife, whom he married in the early 1970s. Eventually, around 1995, Hersh decided to write it all down. The words came excruciatingly slowly. “Two lines a day,” he recalls, when we meet at his comfortable home just north of Leeds. “But I wrote it, and then after that I could speak, I could talk about it.”