Difference between revisions of "Category:Nero (subject)"

| Line 103: | Line 103: | ||

* @2017 Gabriele Boccaccini, University of Michigan | * @2017 Gabriele Boccaccini, University of Michigan | ||

}} | |||

{{WindowMain | {{WindowMain | ||

|title= [[Nero (literature)]] | |title= [[Nero (literature)]] | ||

| Line 140: | Line 140: | ||

|px= 38 | |px= 38 | ||

|content= | |content= | ||

* [[Pseudo-Seneca. Octavia (1484 Gallicus), play (ed. princeps)]] | * [[Pseudo-Seneca. Octavia (1484 Gallicus), play (ed. princeps)]] | ||

| Line 154: | Line 153: | ||

* [[Imperium: Nero (2004 Marcus), feature film]] | * [[Imperium: Nero (2004 Marcus), feature film]] | ||

* [[Ancient Rome: Nero (2006 Murphy), TV film]] | * [[Ancient Rome: Nero (2006 Murphy), TV film]] | ||

}} | }} | ||

|} | |} | ||

|} | |} | ||

Revision as of 02:16, 5 June 2017

|

Nero (Home Page)

< People : Peter -- Paul of Tarsus -- Simon Magus >

Nero -- Overview Early Career Nero was born in Antium, near Rome in 37 CE as Lucius Domitius Ahenobarbus. He was the only son of Gnaeus Domitius Ahenobarbus and Agrippina the Younger, sister of Gaius Caesar. In 49 CE, after that Claudius married Agrippina, Lucius Domitius was officially adopted in 50 CE and renamed Nero Claudius Caesar Drusus. As Nero was older than his step-brother, Britannicus, he became heir to the throne. Nero was proclaimed an adult in 51 CE. He was then appointed proconsul. In 53 CE, he married his step-sister Claudia Octavia. Imperial Succession Nero succeeded to Claudius in 54 CE. The ancient tradition presents Nero first five years of rule as excellent, the quinquennium neronianum. In this period the young Nero was assisted by his mother Agrippina, Burrus, the praefectus praetorius, and his tutor, Seneca the philosopher. In 55 CE, Nero had his step-brother Britannicus poisoned. From then onwards, Nero resisted the influence of his mother, and her advisors. In the same year, he removed Marcus Antonius Pallas, an ally of Agrippina, from his position in the treasury. Finally in 59 CE, Nero had his mother executed. He also divorced and later executed Octavia to marry Poppaea Sabina. With the sudden death of Burrus in 62 C.E., and the retirement of Seneca, Nero was to rule alone. Afterwards, surrounded by new advisors, the rule of Nero assumed the characters of a Hellenistic monarchy. In the last years of rule, Nero was assisted by the new praetorian praefectus Ofonius Tigellinus. Nero showed much sympathy to Greek culture. In 60 C.E., he introduced in Rome, public games in the Greek fashion, the Neronia, and in 66 C.E., Nero left for Greece to perform at the various Greek games. By then, Nero’s rule had become quite unpopular with the Senate. Nero executed various people between 62 and 63 CE, including Pallas, Gaius Rubellius Plautus, Faustus Sulla and Doryphorus. Nero’s difficulties with the Senate resulted in the Pisonian conspiracy in 65 C.E. However the conspiracy was unsuccesful in consequence of a delation. Its members, including Seneca, Lucanus, Petronius Arbiter, were either executed or committed suicide. On the other side Nero was much popular with the lower classes, which were protected with various laws. In 64 CE, a huge fire devastated the city of Rome. Nero, after the great fire of Rome, erected a huge palace in the center of Rome, the Domus Aurea. Other building projects were the draining of the Ostia marshes, and an attempt to have a canal dug at the Isthmus of Corinth. Nero foreign policy was much successful. In the West in Britannia the revolt of Boudicca, queen of the Iceni, was repressed in 61 C.E. by the governor Gaius Suetonius Paulinus. In the East Armenia was brought from Parthian vassalage to Roman influence. In 55 CE, the kingdom of Armenia overthrew the pro-Roman ruler Rhadamistus, replacing him with the Parthian prince Tiridates. Nero sent in his general Gnaeus Domitius Corbulo, who defeated the Parthians. Once more in 58 CE, the Parthian king Vologases I invaded Armenia. Corbulo defeated the invaders and Tiridates had to retreat. Nero crowned as King of Armenia Tigranes, as the new ruler of Armenia. Corbulo was appointed governor of Syria. As Nero nominee in 62 CE, invaded Parthia. The war lasted till 63 CE. In 66 C.E. Tiridates, a member of the Parthian royal family came to Rome to receive the diadem of Armenia from Nero’s himself. Nero rule was overthrown in 68 C.E. by a series of rebellions in the West. Betyween 67-68 CE, Vindex, the governor of Gallia Lugdunensis, rebelled against Nero. Vindex asked the support of Galba, the governor of Hispania Citerior. However Virginius Rufus, the governor of Germania Superior, defeated Vindex's forces who committed suicide. Yet, by June of 68 CE, the senate voted Galba as emperor and declared Nero a public enemy. In the same year Nero committed suicide.

Nero, the Jews and Judaea It seems that the Jews living in Rome fared well under Nero’s rule. A Jewish actor, Alityros (Aliturus), lived at his court (Josephus, Vita 3). His second wife, Poppaea, according to Josephus, showed some sympathy for the Jews. However it is unclear the relationship between the Jews and the Christian community in Rome during Nero’s rule. According to Tacitus, Nero had the Christians accused of the great fire in 64 CE and probably persecuted. It is usually contended that the number 666 of the evil beast in Revelation (13:17-18) is a code for Nero. Both Peter and Paul are believed to have been executed in Rome at that time. As the episode recorded happened after Paul’ coming to Rome, it is possible that by then the Jewish and the Christian communities were already separated entities, that the “parting of the ways” was by then consumed. This can explain why the persecution of 64 CE is not referred by Josephus, and why Tacitus clearly defines the Christians and not the Judaeo-Christians as the targets of the persecution. Herod Agrippa II remained in Rome at least till 52 CE, and possibly till 56 CE, therefore well after the accession of Nero. During this period, Agrippa II was instrumental in helping two Jewish delegations meeting the Emperor. In 55 CE, Nero added to the territories of his kingdom, which from 48 CE, included Chalcis, and from 53 CE, instead of it, the tetrarchies of Philip and Lysanias, the cities of Tiberias and Taricheae in Galilee, and Julias, with fourteen villages near it, in Peraea. In Judaea, proper, however, Nero was quite unsuccessful. As governor of Judaea, he first confirmed Antonius Felix (appointed by Claudius in 52 CE), then replaced him with Porcius Festus (58-62), Clodius Albinus (62-64), and Gessius Florus (64-66). None of them took any effective decision to mitigate the situation. Clodius Albinus, who, corrupted by the Gentile of Caesarea Maritima, in 60-62 CE asked from Nero to revoke the isopoliteia of the Jews living there. This was, according to Josephus, the first step in the Jewish War. In 66 CE the population of Jerusalem rebelled against the governor Gessius Florus, who appealed to Cestius Gallus, governor of Syria. However his army was defeated at the Battle of Beth Horon. Nero reacted decisively only after the outbreak of the rebellion in 66, by appointing Vespasian commander-in-chief of the army in Judaea.

Nero -- History of research Related categories External links

Highlights (scholarship)

|

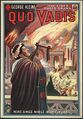

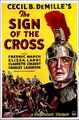

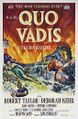

At the end of the 19th century, Quo Vadis made Nero one of the most malicious and unforgettable villains of the history of literature, music and cinema. But since the publication in 1484 of the editio princeps of the Latin tragedy Octavia attributed to Seneca, Nero has been a main character in Western fiction. Quo Vadis only strengthened his connections with Christian Origins and promoted a religious interpretation of his "madness." The first plays on Nero appeared in the 17th century in England (Matthew Gwinne 1603; Nathaniel Lee, 1675; and others), and Italy (Biancolelli, 1666; Boccaccio , 1675). Since the beginning there were no nuances in the interpretation of Nero; he was introduced as "Rome's greatest tyrant." Already in 1642 Nero was introduced in the Italian opera by Claudio Monteverdi in L'incoronazione di Poppea and in the oratorio. Numerous works continued to be written in the 18th century, including the opera Agrippina by George Fridrich Haendel and the play Ottavia by Vittorio Alfieri. In the 19th century, in addition to opera (Anton Rubinstein) and theatre (Pietro Crossa), Nero became the protagonists of many historical novel, from Ernst Eckstein to Then came the paintings of Henryk Siemiradzki and the ciclone "Quo Vadis? by Henryk Sienkiewicz and The Sign of the Cross by Wilson Barrett. The cinema immediately capitalized on the Nero craze. After the first shorts, Guazzoni's epic movie Quo Vadis? (1913) was a smashing success, that numerous other films tried to imitate. The success was repeated in 1932 by Cecil B. DeMille who in his version of The Sign of the Cross presented an ingenious combination of spectacle, violence, sex, and the moral victory of religion, which proved to be very popular with moviegoers. The appeal of Nero as a dramatic character in fiction remained strong for the entire 20th century Unlike other figures from antiquity, whose memory was once very much alive but who are now almost forgotten in popular culture, Nero has made a quite impressive transition to the new millennium, thanks to a series of successful movies, novels, and TV series.

Highlights (fiction)

|

Pages in category "Nero (subject)"

The following 96 pages are in this category, out of 96 total.

1

- Pseudo-Seneca. Octavia (1484 Gallicus), play (ed. princeps)

- Neronis encomium (Praise of Nero / 1562 Cardano), book

- Nero (1603 Gwinne), play

- L'incoronazione di Poppea (The Coronation of Poppaea / 1642 Monteverdi / Busenello), opera (music & libretto), Venice premiere (cast)

- Agrippina (1665 Lohenstein), play

- Il Nerone (Nero / 1666 Biancolelli), play

- Britannicus (1669 Racine), play

- Claudio Cesare (Claudius Caesar / 1672 Boretti / Aureli), opera (music & libretto), Venice premiere

- Il Nerone (Nero / 1675 Boccaccio), play

- The Tragedy of Nero, Emperor of Rome (1675 Lee), play

- Piso's Conspiracy (1676 Lee), play

- Il Nerone (Nero / 1677 Liberati / Ficieno), oratorio (music & libretto)

- Il Nerone (Nero / 1679 Pallavicino / Corradi), opera (music & libretto), Venice premiere

- Epicharis (1685 Lohenstein), play

- Agrippina in Baia (1687 Bassani / Contri), opera (music & libretto), Ferrara premiere

- L'ingresso alla gioventù di Claudio Nerone (The Coming of Age of Nero / 1692 Giannettini / Neri), opera (music & libretto), Modena premiere

- Nerone fatto Cesare (Nero Made Emperor / 1692 Perti / Noris), opera (music & libretto), Venice premiere

- Nero = Il Nerone, German ed. (1693 Strungk / Thymich / @1679 Corradi), opera (music & libretto), Leipzig premiere

- Nero = Il Nerone, German ed. (1695 Meder / @1693 Thymich / @1679 Corradi), opera (music), Danzig premiere

- Nerone fatto Cesare (Nero Made Emperor / 1695 Scarlatti / @1692 Noris), opera (music), Naples premiere

- La fortezza al cimento (Nero / 1699 Aldrovandini / Silvani), opera (music & libretto), Venice premiere

- La mort de Néron (The Death of Nero / 1703 Péchantrès), play

- Agrippina (1709 Haendel / Grimani), opera (music & libretto), Venice premiere (cast)

- Nerone fatto Cesare (Nero Made Emperor / 1715 Vivaldi / @1692 Noris), opera (music), Venice premiere

- Nerone (Nero / 1721 Orlandini / Piovene), opera (music & libretto), Venice premiere

- Nerone (Nero / 1724 Vignati / @1721 Piovene), opera (music), Milan premiere

- Nerone detronato (Nero Dethroned / 1725 Pescetti / Cimbaloni), opera (music & libretto), Venice premiere

- Nerone = La fortezza al cimento (Nero / 1735 Duni / @1699 Silvani), opera (music), Rome premiere

- Colección de varias historias (1767-1768 Santos Alonso), novel

- Ottavia (Octavia / 1783 Alfieri), play

- Épicharis et Néron; ou, Conspiration pour la liberté (Epicharis and Nero / 1794 Legouvé), play

- Julia of Baiae; or, The Days of Nero (1843 brown), novel

- Rome et la Judée au temps de la chute de Néron (1858 Champagny), book

- Nerón (1866 Rubí, Alba y Peña), play

- Nero, the Parricide (1870 Anderson), play

- Nerone (Nero / 1872 Cossa), play

- Geschichte des römischen Kaiserreichs unter der Regierung des Nero (History of the Roman Empire under the Government of Nero / 1872 Schiller), book

- Nero (1875 Story), play

- Néron (Nero / 1879 Rubinstein / Barbier), opera (music & libretto)

- Nero (1880 Comfort), play

- (+) Nero (1889 Eckstein), novel

- Rebekah (1889 Jones), novel

- Acte (1890 Westbury), novel

- The Burning of Rome (1892 Church), children's novel

- Beric the Briton (1892 Henty), children's novel

- Neron essayant des poisons sur des esclaves (Nero Trying Poisons on Slaves / 1896 Hatot), short film

- The Sign of the Cross (1897 Barrett), novel

- Nero (1898 Panizza), play

- Quo Vadis? (1901 Zecca, Nonguet), short film

- The Life and Principate of the Emperor Nero (1903 Henderson), book

- Burning of Rome (1903 Paull), music

- The Sign of the Cross (1904 Haggar), short film

- Nero (1906 Phillips), play

- Quo Vadis? (1908 Nouguès / Cain), opera (music & libretto)

- Nero and the Burning of Rome (1908 Porter), short film

- Nerone (Nero / 1909 Maggi), short film

- Quo Vadis? (1909 Nowowiejski / Jüngst), oratorio (music & libretto), Amsterdam premiere

- Au temps des premiers chrétiens (In the Time of the First Christians / 1910 Calmettes), short film

- Nerone (Nero / 1915 Boito), opera (music & libretto)

- Nero (1922 Edwards), feature film

- Nero, the Singing Emperor of Rome (1930 Weigall), book

- Nerone (Nero / 1935 Mascagni / Targioni-Tozzetti), opera (music & libretto), Milan premiere (cast)

- Der falsche Nero (The False Nero / 1936 Feuchtwanger), novel

- Documents Illustrating the Reigns of Claudius & Nero (1939 Charlesworth), book

- When Nero Was Dictator (1939 Cummins), vision

- The Blood of the Martyrs (1939 Mitchison), novel

- Nerone e i suoi tempi (Nero and His Times / 1949 Levi), book

- Néron (Nero / 1955 Walter), book

- Nero: The Man and the Legend (1964 Bishop), book

- L'incendio di Roma (1965 Malatesta), film

- Beware of Caesar (1965 Sheean), novel

- Nero: Reality and Legend (1969 Warmington), book

- Nero, Emperor in Revolt (1970 Grant), book

- The Conspiracy (1972 Hersey), novel

- I, Claudius (1976 Wise), film

- The Flames of Rome (1981 Maier), novel

- Nero: The End of a Dynasty (1984 Griffin), book

- Imperial Patient: The Memoirs of Nero's Doctor (1987 Comfort), novel

- Reflections of Nero: Culture, History, & Representation (1994 Elsner, Masters), edited volume

- Nero (1997 Shotter), book

2

- Nero: The Man Behind the Myth (2000 Holland), book

- Quo Vadis? (2001 Kawalerowicz), feature film

- The Last Disciple (2004 Hanegraaff/Brouwer), novel

- Imperium: Nero (2004 Marcus), feature film

- The Third Princess (2005 Boast), novel

- The Last Sacrifice (2005 Hanegraaff/Brouwer), novel

- Nero (2003 Champlin), book

- Cristo, Nerone e il segreto di Maddalena (2006 Arcucci, Ferri), novel

- Ancient Rome: Nero (2006 Murphy), TV film

- L'incendie de Rome (2006 Nahmias), novel

- The Great Fire of Rome: The Fall of the Emperor Nero and His City (2010 Dando-Collins), book

- A Companion to the Neronian Age (2013 Buckley, Dinter), edited volume

- Nero in Opera: Librettos as Transformations of Ancient Sources (2013 Manuwald), book

- Dying Every Day: Seneca at the Court of Nero (2014 Romm), book

- The Confessions of Young Nero (2017 George), novel

- Divo Nerone / Divo Nero (2017 Migliacci), rock opera (music & libretto), Rome premiere (cast)

Media in category "Nero (subject)"

The following 9 files are in this category, out of 9 total.

- 1895 * Barrett (play).jpg 333 × 499; 27 KB

- 1895 * Sienkiewicz (novel).jpg 674 × 1,100; 138 KB

- 1913 Guazzoni (film).jpg 330 × 475; 67 KB

- 1914 Thomson (film).jpg 300 × 441; 49 KB

- 1924 D'Annunzio & Jacoby (film).jpg 230 × 345; 46 KB

- 1932 * DeMille (film).jpg 288 × 436; 197 KB

- 1951 * LeRoy (film).jpg 338 × 517; 79 KB

- 1956 Steno (film).jpg 235 × 336; 42 KB

- 1976 Castellacci (film).jpg 288 × 488; 24 KB