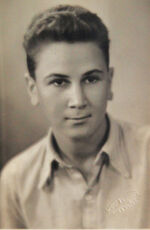

Zdenek Ornest / Zdenek Ohrenstein (M / 1929-1990), Holocaust survivor

Zdeněk Ornest / Zdeněk Ohrenstein (M / Czechia, 1929-1990), Holocaust survivor

- One of the main interpreters of Brundibar

- KEYWORDS : <Theresienstadt> <Auschwitz> <Dachau>

Biography

He was born in Kutná Hora on January 10, 1929.

Travel Eye (05/04/2015)

Life full of twists

Another story from the Terezín ghetto is the remembrance of a great actor and, above all, a great person Zdeněk Ornest. He was born in Kutná Hora on January 10, 1929, as the third son of the Jewish husband and wife Berta and Eduard Ohrenstein, who owned a small fabrics and haberdashery store on Kollarová třída No. 157

Eduard Ohrenstein (October 5, 1881 – November 30, 1936) died of leukemia before the war at the Sanopz Sanatorium in Smíchov. He was buried in the Jewish cemetery in Malešov. After his death, the store was led by Berta Ohrensteinová, born as Rosenzweigová (29 November 1890–6 October 1970), until June 1942, when the Germans confiscated it. In 1941, she was married again to widower Rudolf Pollák, a Jewish business owner from Prague who died during the war in a concentration camp. Berta, now Polláková, was deported to the Terezín ghetto by transport AAb as number 182 from Kolín to Terezín on 5 June 1942 (744 people). Thanks to the job in production of Glimmer (peeling of mica) she was freed. She died at the admirable age of 80 in the house where Zdeněk Ornest lived with his family.

Zdeněk Ornest‘s daughter Ivana Šebková (June 1, 1963) recalls that his father did not talk about his childhood. But he thinks he was influenced by his much older brothers a lot. “He told us how they had asked him when he was about three years old, little Zdeněk, are you a materialist or an idealist? And he answered them, I am little Zdeněk. My father probably had a nice childhood in Kutná Hora. If he ever talked about the worse parts, I recall the story of when he went to the cinema alone already during the occupation, but the film would not begin. Suddenly, the projectionist shouted: The film will not begin until the Jew leaves! All of sudden, everyone at the cinema began to chant – Jews out! My father had to leave, and although he did not want to talk much about it, he made the incident less serious, I think he felt it as a feeling of hurt “

Zděněk‘s eldest brother Ota (July 6, 1913 – August 4, 2002), later a theater dramatist, actor, translator and director of Prague Municipal Theaters, emigrated to England in 1939, where he worked in foreign resistance. He returned to the Republic in 1945.

Zděněk’s second brother Jiří (30. 8. 1919 – September 1, 1941), a promising Czech poet writing under the pseudonym Orten, studied language school in Prague and worked as an archivist. The testimony of his life is found in three diary books (Blue, Brindle, Red) in which he recorded his observations and poems from 1938–1941. He did not publish anymore books. On August 30, 1941, he was hit by a passing German ambulance and suffered the consequences of the injury. It was Jiří Orten, who, after the death of his father and after his brother‘s departure to England, cared for his mother and Zdeněk. He then had to take him to a Jewish orphanage in Prague (the so-called Lauder School in Belgická Street) on Christmas 1940. In October 1942, all orphans were transported to the Terezín Ghetto.

In Terezín, Zdeněk was placed in a boy‘s home – block L417. Their leader was Valtr Eisinger, who developed the ability of boys to formulate everyday experiences, to respond to the reality of the ghetto, and to apply literary ambitions in a secretly- propagated Vedem magazine. Of about one hundred of the boys who participated in the texts of the magazine, only 15 survived, including Zdeněk. This was not Zdeněk’s only Terezín activity, he also became the protagonist of the children‘ s opera by Hans Krása – Brundibár, where he played a dog.

“I do not recall,” says Jiří Ornest, Zdeněk‘s nephew and brother Ota‘s son, “that Zdeněk reflecting of his experiences from Terezín. But it is true that he was still a boy when he was there. Maybe he only perceived his forced stay in Terezín as a strange part of his childhood. But what I will never stop regretting is that I did not listen to him more during our joint trips, when he, because he suff ered greatly from insomnia, regularly talked about his experiences until four o‘clock in the morning. And apparently would think about Terezín, but I always fell asleep. Zdeněk had such a special sense of humor. He was not a provocateur, but he could be sarcastic, though he did not show it much. He did not want to antagonize anyone. The desire to avoid confl ict most likely comes from his time spent at Terezín.”

In the Terezín ghetto, Valter Eisinger (May 7, 1913) influenced the life of Zdeněk and many other boys. He was deported to the ghetto on 28 January 1942 from Brno, and thanks to his left-wing thinking, he belonged to the most controversial educators. He even got married to Věra Sommerová in ghetto, in July 1944.

By the end of September 1944, he was transported to the extermination camps of Auschwitz and then to Sachsenhausen. During the march of death to Buchenwald on January 11–13 1945, he was shot. In the Terezín ghetto, in July 1942, Eisinger became the leader of the so-called “Boys ‚Home 1” in the former Terezín school (building L 417) and he organized the boys‘ self-government called the Republic of Škid, in December 1942.

Petr Ginz took over the publishing of the Vedem magazine, which was written by 13&14 years old boys. The magazine was issued weekly during the years 1942–1944, Ginz was the editor- in-chief of the magazine, Jiří Kurt Kotouč was Ginz´s right hand and there was another signifi cant creative member of the editorial board, Zdeněk Ornest, who recalled: “We were led by Professor Eisinger from Brno who worked as a Czech and Literature teacher at the Jewish grammar school.

We created a kind of self-government, and we were called the Republic of Škid, according to the book School Imjeni Dostojevskogo, which was written by Pantělejev. The book is about the Republic of uncared-for children, who gradually became a mature team. The magazine was written on various waste paper, it was written mainly in hand by boys and sometimes typed on a typewriter which was borrowed somewhere in the command offi ce. Actually, there are 800 pages still retained.

It was such a vast diary of our life, where you could fi nd both objective things from Terezín and poets, feuilleton experiments written by young so-called poets. We can say that it is something like extended diary of Anna Franková.

Those days were counted in a particular way and no one was sure about the following one. We eventually experienced the inferior conditions in the camps. So, all the senses for everything were utterly exciting, we swallowed everything we could, even in those limited conditions. So, we enjoyed life to the full.

Petr Ginz also made a series of lectures on the Russian literature, Russian Classicism, talked about the so-called “Pátečníci” (“Friday members”), about Karel Čapek, and he was very happy when we sometimes shared a half loaf of bread with him.

Zdeněk‘s stay in Terezín ended on October 19, 1944, when he was deported in the second to last, ninth transport to Auschwitz as number Es 1017. “Upon arriving in Auschwitz, everyone went straight to the so-called selection. The notorious doctor Mengele placed his father among those who went straight to the gas chamber. His older friends on the opposite side waved at him to run over to them. So, he tried to run over behind Mengele‘s back and other Deathsheads. He succeeded, but as he was running over, the SS caught sight of him and ran toward him. My father, however, told him in German that he was 18 years old, and the SS only waved his hand,” Zdeněk‘s daughter Ivana told us.

Zdeněk Ornest recalled his arrival in Auschwitz as the day, when from the entire transport of 1500 people, 1200 of them was sent in the selection of Dr. Mengele straight to the gas chamber. Zdeněk Ornest was sent to the imaginary “right side” of only three hundred able-bodied prisoners. Even though Mengele sent him to the left, among little children, women and old men, he had managed to get to the side of those who had some time to live, thanks to the chaos that arose that day.

Zdeněk recalls: “I shouted to younger friends: Hello, I‘ll see you in a few days. I did not know what was happening and when I came to the concentration camp E, I just learned that it was a selection. So, all those people in the group I ran away from, went to the gas chambers. During the medical examination in the camp, the doctor said to me that I was stupid, because I did not look like I was going to survive.

Soon, Zdeněk was deported from Auschwitz to the concentration camp of Kaufering and from early 1945 to Dachau, where he was liberated by the Americans.

After returning home, he was reunited with his mother and brother Oto. He graduated from the grammar school in Kutná Hora and went to study at DAMU in Prague where he graduated in 1950 – acting. His fi rst engagement was the Regional Theater in Olomouc, where he also met his later wife, Alena (* 20th July 1936), who was at that time a freshman medical student. In 1952 he entered the Nusle Theater of Music (today Na Fidlovačce Theater) and from 1962 he worked at the SK Neumann Theater in Libeň (now Theater under Palmovka). In 1960 he also married Alena after fi ve years, and a year later his daughter Ivana was born. “After the graduation, I was very ill and Zdeněk came to me at the hospital and said,” I think I‘ll probably marry you. For years he would say to me, “I thought you were on your deathbed, so I off ered to marry you,” Alena said with a smile.

Zdeněk got into the film industry in the mid- 1960s when he appeared in the fi lm the Case of Daniel (1964). However, he got more opportunities in the 1980s, for example in the series such as Ambulance (1984), the Train of Childhood and Hope (1985) or Prague Panoptikum (1987). He personally impressed with the character of a German merchant in the film A friend in the Rain (1988). Shortly before his death, he worked with his brother Oto at Prague Municipal Theaters. Zdeněk Ornest died suddenly – November 4, 1990.