(++) Johannespassion (St. John Passion / 1724 Bach), oratorio

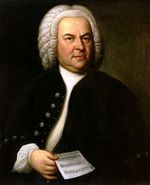

Johannespassion <German> / St. John Passion (1724) is an oratorio by Johann Sebastian Bach (mus.).

Abstract

“Der für die Sunde der Welt gemartete und sterbende Jesus” (Johann Sebastian Bach, nach Barthold Heinrich Brockes, Christian Heinrich Postel & Christian Weise), BWV 245,

Characters

Evangelista (T); Jesus (Bs); Petrus (Bs); Pilatus (Bs); Ancilla (S); Servus (T). S; A; T; Bs.

Editions, translations

Premiered in Leipzig, Germany: Nicholaskirche, 7 April 1724.

Bach revised his work in 1725 (2nd version), 1730 (3rd version) e in 1749 (4th version).

Sound Recordings

See ODE:

- 1938, settembre, 22, Buenos Aires.

Interpreti: Káláman Pataky; Herbert Janssen; Emanuel List; Emanuel List; non indicati. Inoltre: Margarita Perras (Uxor Pilati, S). Margarita Perras; Karin Branzell; Káláman Pataky; Herbert Janssen. Coro e Orchestra Teatro “Colón” Buenos Aires, dir. Erich Kleiber.

- 1948, aprile, 18, Basel, Cattedrale.

Interpreti: Julius Patzak; Charles Panzéra; Fritz Mack; Fritz Mack; non indicati. Maria Stader; Elsa Cavelti; Julius Patzak; Fritz Mack. "Gesangsverein" e "Orchestergemeinschaft" Basilea, dir. Hans Münch.

- 1950, marzo, 23.

Interpreti: Helmut Krebs; Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau (Br); Gerhard Niese; Leopold Clam; non indicati. Gunthild Weber & Ina Brosow; Lotte Wolf-Mattaeus; Herbert Froitzheim; Gerhard Niese. Coro e Orchestra "Rundfunk im Amerikanischen Sektor" (RIAS) Berlino, dir. Karl Ristenpart.

- 1950, Wien.

Interpreti: Ferry Gruber; Walter Berry; Harald Buchsbaum; Leo Heppe; Gisela Rathauscher; Fritz Uhl. Gisela Rathauscher; Elfriede Hofstaetter; Rudolf Kreuzberger; Walter Berry. Coro camera Accademia e Orchestra Sinfonica Vienna, dir. Ferdinand Grossmann.

● 1951

Interpreti: Blake Stern; Mack Harrell (Br); Paul Ukena; Daniel Slick (Br); Florence Fogelson; Walter Carringer. Adele Addison; Blanche Thebom; Leslie Chabay; Paul Matthen. Corale “Robert Shaw”, Corale Collegiata e Orchestra “RCA Victor”, dir. Robert Shaw (cantata in inglese, traduzione Julius Herford & Robert Shaw).

- 1951

Interpreti: non indicati. Kathryn Harvey; Gertrude Pfenninger; Ernst Häfliger; Derrik Olsen. Coro "Bach" Zurigo e Orchestra Sinfonica Winterthur, dir. Bernhard Henking.

Etc. etc.

Antisemitism in Bach's Johannespassion?

@ Gabriele Boccaccini, University of Michigan (a presentation at St. Francis Church, Ann Arbor, MI; March 15, 2016)

The controversy surrounding the allegedly "anti-Semitic" character of Bach’s St. John Passion has aroused since the 1980s: to the point that there were protestors objecting to the performance of an "anti-Semitic" oratorio at Swarthmore College in 1995 and at the Oregon Bach Festival in 2000.

The irony is that Jews have played a decisive role in preserving the oratorio for posterity as well as in elevating Bach to his current position among the world's best known and most widely performed composers. It was the Itzig and Mendelssohn families who saved Bach's music from obscurity. And it was Felix Mendelssohn-Bartholdy, a convert to Christianity but very proud of this Jewish identity, who led the Bach revival in the 19th century.

Now, it is true that the libretto contains phrases that seems to emphasize the responsibility of "the Jews" as the driving force behind the crucifixion of Jesus. The charge is serious as the blame against the Jews as the "killers" of Jesus not only was used as a justification for their discrimination but also generated some of the worst anti-semitic prejudices, including the idea that "blood-thirsty" Jews were eager even to kill Christian children to inflict them the same suffering as Jesus', and used their blood in their rituals.

In reality the situation is more complex.

(1) In spite of a legacy of antisemitism that went back to Luther himself, Lutherans at the age of Bach were generally tolerant.

For example, in April 1715, the Hamburg Senate issued a proclamation relating to Easter renditions of John's Passion. It asserted that: "The right and proper goal of reflection on the Passion must be aimed at the awakening of true penitence… Other things, such as violent invectives and exclamations against… the Jews… can by no means be tolerated."

In the same year the theologians at the University of Leipzig signed a declaration in which they denied there was any evidence that "the Jews" had a murderous nature and used Christian blood in their rituals. At the time of Bach six Jewish families had been granted permission to live within the town limits. There is no evidence of anti-Semitic tensions.

(2) We need to consider the structure of St. John Passion. Its libretto consists of the Luther Bible’s literal translation (from Greek into German) of John 18-19 in the form of recitatives and choruses, along with extensive commentary in the form of interspersed arias and hymns. Bach could not alter John's account of the Passion, yet he had discretion over what additional material to include in its musical setting. He drew on Der für die Sünde der Welt gemarterte und sterbende Jesus / The Story of Jesus, Suffering and Dying for the Sins of the World, a 1712 libretto by Barthold Heinrich Brockes which Handel (among others) had set to music before him in 1719.

The way in which Bach used Brockes' libretto reveals a consistent pattern. First of all, Bach refrained from borrowing any of non-gospel passages that were more hostile to Jews.

Second, Bach did hot hesitate to modify Brockes' poetry. For instance, Brockes describes the Jews as a murderous people who needs to abandon "Achshaph’s dens of murder" and repent in front of the Calvary. In Bach instead the emphasis is on his fellow Christian listeners who have to abandon their "dens of torment" and repent in front of the Calvary.

Finally, none of the passages Bach added refer to "the Jews" but firmly locate the blame for Jesus's death in the sinful behavior of all errant humankind. Commenting on Jesus being struck by one of the attendance of "the Jews", Bach says: "“Who has struck you so? ... I, I and my sins, which are as numerous as the grains of sand on the seashore; they have caused you the sorrow that strikes you and the grievous host of pain.”

Even from the musical point of view there is no evidence whatsoever that Bach had any intention to use dissonance and repetition to convey hostility towards the Jews. As far as we can judge, Bach acted perfectly in line with the recommendations of the Lutheran Church of Hamburg.

The conclusion is that if there is antisemitism in Bach's libretto, it does not come from Bach himself but from the Gospel text. The real question is not whether Bach was antisemitic (he certainly wasn't), but whether the gospel of John is antisemitic. In fact over the centuries the Gospel of John has been used by any sort of Jewish-haters to support their anti-Semitism.

Once again, the situation is far more complex that it might appear at first sight.

(1) First, from the historical point of view it is certainly puzzling that the author of the Gospel of John had the intention to condemn "the Jews", knowing - as he knew - that Jesus, all his family and disciples were Jewish, and most likely being Jewish himself. It does not make sense.

(2) The term "the Jews" which translates the Greek "hoi Iudaioi" does not have the same meaning in Greek as in German or English. For us "the Jews" are all the members of the Jewish people. For the Gospel of John, hoi Iudaioi are a group of Jews who are enemies of another group of Jews, that is, the early followers of Jesus. By translating hoi Iudaioi with "the Jews", we have transformed an inner Jewish debate into a confrontation between a supposedly non-Jewish group (the Christians) and the entire Jewish people, so betraying the original meaning of the text. The earliest gospels are more accurate, they called their opponents with their names, Sadducees or Pharisees; at the end of the first century, the community of John felt more marginalized and isolated and tended to include all their opponents under the same label "hoi Iudaioi". And yet we should never forget that they looked at Jesus and themselves as faithful Israelites. Even in their sharp criticism of the authorities of the Temple (which by the way was shared but other Jewish groups of the time), they recognized a great deal of diversity; they knew that not even all "Jews", like Nicodemus or Joseph of Arimathea, were hostile to them.

Once we have realized that "the Jews" in the Gospel of John (and in Bach's libretto) are the result of a mistranslation, what should we do?

Some attempts have been proposed to rewrite extensively the libretto to make it less "Judeophobic", but do we have the right to rewrite the past, when we do not like it? or to judge an old text with the some measure as if it were written today?

Some have suggested some small accommodations to eliminate the mistranslation of the term "hoi Iudaioi" For instance, German-American composer and conductor Lukas Foss (1922-2009), who emigrated to the US as a refugee from Nazi Germany, used to change the word “Juden” (“Jews”) to “Leute” (“people”). It might not be a very precise translation, too, but at least it had the advantage of getting rid of any Antisemitic connotation, without altering dramatically the text.

Maybe the best thing is to do what we are doing today, to educate the audience (church-goers as well as concert-goers) that words change their meaning over time, and may not mean today what they meant yesterday. The fact the some Jews (and by the way, I must admit, some Italians too) were involved in the crucifixion of Jesus does not mean that all Jews (and I hope you also would agree, not all Italians) should be blamed for that.

We should always remember, as Mark Chagall has reminded us in this beautiful painting, that Jesus, the founder of Christianity, was one of the many Jews victims of violence and persecution.

Today's concert of Bach's St. John Passion is performed at a Catholic Church. I think it is not inappropriate to conclude my presentation by repeating what the Vatican II Council solemnly stated in the document "Nostra Aetate" in 1965:

"True, the Jewish authorities and those who followed their lead pressed for the death of Christ; still, what happened in His passion cannot be charged against all the Jews, without distinction, then alive, nor against the Jews of today ... the Jews should not be presented as rejected or accursed by God, as if this followed from the Holy Scriptures ... Mindful of the patrimony she shares with the Jews and moved not by political reasons but by the Gospel's spiritual love, [the Church] decries hatred, persecutions, displays of anti-Semitism, directed against Jews at any time and by anyone."

Bibliography

- Michael Marissen, Bach’s St. John Passion and the Jews

- David Conway, J S Bach, the Misunderstood Musician

- James R. Oestreich, Of Bach and the Jews in the 'St. John Passion'

- Caroline Grover, Anti-Semitism in Bach’s St. John Passion

External links

- Pages with broken file links

- 1724

- Fiction--1700s

- Fiction--German

- Music--1700s

- Oratorios

- German language--1700s

- Made in the 1720s

- Johannine Studies--1700s

- Johannine Studies--German

- Johannine Studies--Fiction

- Historical Jesus Studies--1700s

- Historical Jesus Studies--Fiction

- Historical Jesus Studies--German

- Passion of Jesus (subject)

- Passion of Jesus--music (subject)

- Jesus of Nazareth (subject)

- Jesus of Nazareth--fiction (subject)

- Jesus of Nazareth--music (subject)

- Gospel of John (text)