Category:Black King (subject)

Black King

This page was edited by Gabriele Boccaccini, University of Michigan

Abstract

According to the Gospel of Matthew, wise men (Magi) from the East come to Jerusalem seeking “the king of the Jews.” The term “magus” (plural magi) was generally applied to dream interpreters, astrologers, or sorcerers from the area of Persia (modern Iran). Accordingly, on sarcophagi, in frescoes, or within by mosaics, these Persian magi were distinguished by red Phrygian caps ascribed to those from the East.

From Magi to Kings: the "African King"

Although the biblical text does not specify how many magi were present, they were thought to be "three" because they brought three gifts to Jesus. The idea that they were "Kings" bearing gifts was likely taken from Psalm 72, which speaks of a just ruler who defends the cause of the poor and crushes the oppressor and to whom foreign kings bring gifts and pledge obedience.

According to Christian traditions, the bones of the "Three Kings," found in Jerusalem by Helena, were presented in 344 to the city of Milan by the Emperor Constantine, as a gift for the election of the new Archbishop Eustorgius I and preserved in a sarcophagus in the Basilica of Saint Eustorgius. By the 6th century CE, they had been named Caspar (or Jaspar), Melchior, and Balthazar.

While magi were understood to be wise men from the East, one magus became regarded as “darker” than the others. As early as the 8th century CE, an Irish text described Balthazar as fuscus, a Latin word meaning “dark” or “swarthy.” Yet, this was a description not of his skin color but only his hair and beard. In addition, the three kings were regarded as representative symbols of Africa, Asia, and Europe; Balthasar (or Caspar) was the "King of Africa." By the thirteenth century texts were variously specifying that they had come from Persia, India, Arabia, the Mediterranean, Nubia, Sheba, and other legendary lands, but none of them was "black."

Around 1370 the Carmelite scholar Johannes of Hildesheim took on an ambitious task: to compile an authoritative account of the Three Kings (a.k.a. the Three Magi) from disparate biblical, historical, and legendary sources. By this point the outline of their story was well-established, but many details were disputed. Johannes’s work enjoyed great popularity and did much to establish a single authoritative version of the legend. According to this narrative, travelling together back to India, the three kings founded a chapel on the Hill of Vaus, the site where the star had first been seen. They made a pact to return every year and, eventually, to be buried there. The Apostle Thomas, whose task was to spread the Gospel to the east, found them here, baptized them, and named them archbishops, and after his death they appointed spiritual and temporal leaders in their region. Johannes had clear ideas about the origins of the three kings: he identified Balthasar as the king of Sheba, Melchior as the king of Nubia and Arabia, and Caspar as the king of the legendary isle of Tharsis and a “black Ethiop”.

From the "African King" to the "Black King"

Exactly how and when the "African King" became also the "Black King" is debatable. Undoubtedly, the city of Cologne, Germany played a leading role in spreading the cult of the Three Kings in Europe. In June 11, 1164 the Emperor Frederick Barbarossa sacked Milan [Italy]. Among his most precious booty were the remains of the Three Magi, which with great pomp were transported to the Cathedral of Saint Peter in Cologne [Germany]. A magnificent shrine was built to contain the remains of the Magi, and the construction of the new Cathedral began in 1248 to accommodate the thousands of pilgrims.

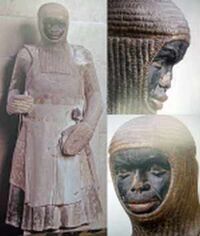

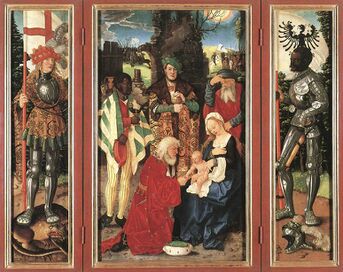

Now, in the Cologne tale the African King was Caspar and the three Magi were still portrayed as "white." However, the patron saint of the city was St. Maurice who was often depicted in Germany as black (his statue as a black soldier in Magdeburg Cathedral dates from around 1240). It is possible that the influence of the cult of St. Maurice and other black saints in Germany made it easier to imagine one of the three Magi as black. Die Anbetung der hl. Drei Könige, Außenflügel des Wurzacher Altars (1437), by Hans Multscher, provides one of the earliest examples of the "Black King" [see below, left]. The connection between the Black King and St. Maurice would remain apparent in Germany, as one can see in The Three Kings Altarpiece (1507), by Hans Baldung, where the "white" St. George and the "black" St. Maurice form a triptych with the Adoration of the Magi (and the Black King) [see below, right]

The image of the Black King moved beyond Germany when around 1460 the young Flemish artist Hans Memling (or another unidentified painter from the same workshop) chose to copy the renowned Columbia Adoration Altar piece by their master Jan van Den Weyden (c. 1400–1464), and made one telling alteration. The author painted its third white Magus as "black," while in the original he had dark hair but was unmistakably "white." In 1479-80 Memling first took up this iconography with only a few variants in the Triptych of Jan Floreins and then developed it in his Adoration masterpiece (now at the Prado Museum).

In Rogier van der Weyden's Adoration (1450-55) there is no black King. The altarpiece was in the Church of St. Kolumba in Cologne, Germany (now in the Alte Pinakothek, Munich, Germany).

In the Polyptych of Hulin de Loo (1460-64, attributed to young Hans Memling, or other painter of the same workshop) the Black King is there. Now in the Prado Museum, Madrid, Spain.

And so is in Hans Memling's Triptych of Jan Floreins (1479), now in Old St. John's Hospital, Bruges, Belgium.

And in Hans Memling's Adoration masterpiece (1479-80), now in the Prado Museum, Madrid, Spain.

Hans Memling's works were copied or imitated by the leading artists of the day and through those copies, the image spread throughout Europe in the work of artists of varying skills, notably, Andrea Mantegna, Hieronymous Bosch, and Albrecht Dürer. The popularity of the subject at the end of 15th century was such that Johannes of Hildesheim's Historia de gestis trium regum was among the very first printed books, in Germany, Italy, England, France, Denmark and the Netherlands. Interestingly, in the 1483 German edition of the work, 2 of the 12 illustrations depicted one of the three Kings as black, thus giving authority and normativeness to the new trend. Within Renaissance and Baroque art the Adoration scene would now commonly included the "Black King" (generally identified with Balthasar and occasionally with Caspar).

Fairly common in Northern European art, the Black King was less frequent in Florentine Renaissance art, where in works of artists such as Benozzo Gozzoli, the Three Kings remained rigorously "white." Central Italian artists were among the last to adopt the image of the Black King, though black attendants were sometimes included in the retinue of three white Magi.

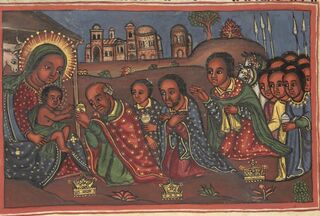

The Three Black Kings of Ethiopia

In the meantime, a completely different development occurred in Ethiopia. A 16th cent. Ethiopian book claims that the Magi, the 3 kings who visited Jesus were all Ethiopians. Legend has it that they consumed coffee on their journey to stay awake. In their memory coffee in Ethiopia is today served 3 times. Serving are named after the Magi Abol, Tona & Baraka.

Blackness and Exoticism

The Black Magus challenged the stereotypical European Renaissance concept of a black African in that rather than portrayed as a barbarian, his fashionable, often outlandish, clothes signified him to be civilized.

However, the Black King did not represent an inclusive, positive standard for viewing Blackness. Rather, he served as a metaphor for the spread of Christianity as extending throughout three continents.

In addition to his blackness, he has three distinct attributes to indicate his exoticism to Renaissance viewers: he wears earrings (no white Magus has been found to be wearing one), opulent dress, and is presented as narcissistic, isolated, neither interacting nor making eye contact with Baby Jesus--all emphasizing his “otherness” and creating a cultural divide between himself and the white Magi. The divide is further emphasized by him invariably being last in the line.

Only by some artists the "Black King" was portrayed in a fully dignified fashion, or took central stage in the Adoration scene. The most conspicuous examples of this trend are those offered in the 17th century by some Dutch painters such Peter Paul Rubens or Hendrik Heerschop (see above).

Even more unusual are paintings in which the Black King interacts with Baby Jesus, of which this work by Bartolomeo Biscaino (1650) offers a rare example.

The Demise and Revival of the Black King

After reaching its peak in the 16th-17th century, the subject of the Adoration of the Magi declined in popularity, and so the image of the Black King.

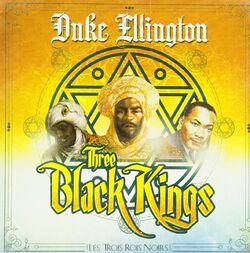

In more recent times the idea of the "Black King" has been revived in an inclusive fashion by Gian Carlo Menotti in Amahl and the Three Night Visitors (1951) and Duke Ellington in Three Black Kings (1974), as well as in popular children's books.

A Look to the Future: Why not a "Black Queen"?

One thing the Christian tradition has never challenged--the Magi (or sages) were males. But this is not said. The text makes no reference to gender any more than it does to number or skin color. The Greek term Magoi could refer to both male and female sages. We know that ancient Magi included women. And the closest parallels we have in the Bible refer to two women: the Queen of Sheba, who brought gifts to Solomon, and the woman who in Mark and Matthew came to Jesus "with an alabaster jar of very expensive perfume, which she poured on his head" (see Anointing of Jesus). How can be then overlook the fact that in the Jewish tradition "Lady Wisdom" (hochma; Gk. sophia) is a woman? Imagining the Magoi as "Queens" or "Female sages" is no less daring than imaging them as "Kings" or "Male Sages."

These consideration have led scholars such as Benedict Thomas Viviano (in a 2010 article), artists and Christian congregations to open up the possibility that the Magoi included women and that the "Adoration" does not necessarily have to be a male-only scene but could be depicted as an inclusive scene not only in terms of skin color but also in terms of gender.

"In Janet McKenzie’s interpretation of the Magi, women around the world find an image of the Epiphany that includes and validates their encounters with the One Who Saves, celebrated here in the powerful, protective and tender manifestation of a mother and her child, embraced and nurtured by a loving community. Here is global inclusiveness and a vision of mutuality and interdependence – the giving and receiving of the three gifts essential to life itself: presence, love and daily bread. Epiphany proclaims again and anew: Christ for all people. God’s favor extends to all!"

Exhibits

"Balthazar: A Black African King in Medieval and Renaissance Art", an exhibit curated by Kristen Collins and Bryan Keene at The Getty Center in Los Angeles, CA in 2019-2020. See Virtual tour

- "Early medieval legends reported that one of the three kings who paid homage to the newborn Christ Child in Bethlehem was from Africa. But it would be nearly one thousand years before artists began representing Balthazar, the youngest of the magi, as a Black African. This exhibition explores the juxtaposition of a seemingly positive image with the painful histories of Afro-European contact, particularly the brutal enslavement of African peoples."

"Sensing the Unseen: Step into Gossaert's 'Adoration", The National Gallery, London, UK (9 December 2020 – 13 June 2021)

- "Take your first step into Jan Gossaert’s world of intricate detail, technical mastery and rich meaning in a new Gallery experience where you’ll be surrounded by the sights and sounds of his 500-year-old masterpiece ... In 'The Adoration of the Kings’, Gossaert has compressed time and space into a richly detailed, imagined setting where some elements of this familiar Christian scene are immediately clear and others are hidden for us to discover: the weave of fabric, Gossaert’s fingerprint in the green glaze where he blotted it with his hand, thistles and dead nettles, hairs sprouting from a wart on a cheek, a tiny pearl, a hidden angel ... To help you uncover the unseen, Balthasar - the Black king, pictured here with a gift of myrrh at Christ’s side - will share his journey through a world on the brink of change to be present at this moment of transformation ... Through soundscapes, spoken word, hi-resolution digital imagery and gesture-based interaction you will go on your own personal journey to discover not only the visual riches of the painting but also why it tells more than a Christmas story ... This is an opportunity to not only stand in front of the painting but immerse yourself in its world and the artistry that built it."

Bibliography

Alain Locke. The Negro in Art: A Pictorial Record of the Negro Artist and of the Negro Theme in Art. Washington, DC: Associates in Negro Folk Education, 1940.

- A major document of African American Art up to 1940. Includes a discussion of the Black King. With copious notes and artist biographies. Illustrated by Plates of the works of numerous artists.

Paul H.D. Kaplan. The Rise of the Black Magus in Western Art. Studies in the fine arts: Iconography, 9. Ann Arbor, MI: UMI Research Press, 1985.

- The black attendant to the white magi -- The sources and early development of the black magus/king in literature -- The iconography of blacks in fourteenth-century Germany and Bohemia -- Images of the black magus/king to ca. 1450 -- The black magus/king ca. 1450-1500.

Geraldine Heng. The Invention of Race in the European Middle Ages. New York, NY - Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2018.

- In The Invention of Race in the European Middle Ages, Geraldine Heng questions the common assumption that the concepts of race and racisms only began in the modern era. Examining Europe's encounters with Jews, Muslims, Africans, Native Americans, Mongols, and the Romani ('Gypsies'), from the 12th through 15th centuries, she shows how racial thinking, racial law, racial practices, and racial phenomena existed in medieval Europe before a recognizable vocabulary of race emerged in the West. Analysing sources in a variety of media, including stories, maps, statuary, illustrations, architectural features, history, saints' lives, religious commentary, laws, political and social institutions, and literature, she argues that religion - so much in play again today - enabled the positing of fundamental differences among humans that created strategic essentialisms to mark off human groups and populations for racialized treatment. Her ground-breaking study also shows how race figured in the emergence of homo europaeus and the identity of Western Europe in this time.--Publisher description.

Cord J. Whitaker. Black metaphors : how modern racism emerged from medieval race-thinking. Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2019.

- "This book's aim is to investigate the relationship between the idea of blackness and the notion of sinfulness in the literature and culture of the English Middle Ages, with influences from continental European texts as well. Though the main target of Black Metaphors is the Middle Ages, the book also asserts the profound implications of the historical nexus of blackness and sinfulness for modern life and culture"--Publisher description.

Erin Kathleen Rowe. Black Saints in Early Modern Global Catholicism. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2020.

- "From the sixteenth to the eighteenth centuries, Spanish and Portuguese monarchs launched global campaigns for territory and trade. This process spurred two efforts that reshaped the world: missions to spread Christianity to the four corners of the globe, and the horrors of the transatlantic slave trade. These efforts joined in unexpected ways to give rise to black saints. Erin Kathleen Rowe presents the untold story of how black saints - and the slaves who venerated them - transformed the early modern church. By exploring race, the Atlantic slave trade, and global Christianity, she provides new ways of thinking about blackness, holiness, and cultural authority. Rowe transforms our understanding of global devotional patterns and their effects on early modern societies by looking at previously unstudied sculptures and paintings of black saints, examining the impact of black lay communities, and analysing controversies unfolding in the church about race, moral potential, enslavement, and salvation."--Publisher description.

External links

- The Story of the Black King Among the Magi, by Sarah E. Bond and Nyasha Junior (Hyperallegic; January 6, 2020)

- The Story of the Black King Among the Magi, by Sarah E. Bond (January 12, 2020)

- Myrrh mystery: how did Balthasar, one of the three kings, become black?], by Jonathan Jones (The Guardian; 21 December 2020)

- Depicting the Magi: Origins, Gifts and Representing Men of Colour, by Leslie Primo (17 Dec 2018)

Pages in category "Black King (subject)"

The following 23 pages are in this category, out of 23 total.

1

- Adoration of the Magi (1462 Mantegna), art

- Adoration of the Magi (1475 Bosch), art

- Adoration of the Magi (1495 Bosch), art

- Adoration of the Magi (1499 Bosch), art

- Adoration of the Magi (1500 Mantegna), art

- Adoration of the Magi (1504 Dürer), art

- Adoration of the Magi (1511 Kulmbach), art

- Adoration of the Magi (1515 Gossaert), art

- Adoration of the Magi (1519 Beer), art

- Adoration of the Magi (1525 Luini), art

- Adoration of the Magi (1530 Girolamo da Santacroce), art

- Adoration of the Kings (1542 Bassano), art

- Adoration of the Kings (1560 Aartsen), art

- Adoration of the Magi (1619 Velázquez), art

- Adoration of the Magi (1629 Clerck), art

- Adoration of the Magi (1640 Zurbarán), art

- Adoration of the Magi (1650 Biscaino), art

- Adoration of the Magi (1660 Murillo), art

- Adoration of the Magi (1730 Ricci), art

- Adoration of the Magi (1750 Casali), art

- Adoration of the Kings (1753 Tiepolo), art

- Adoração dos Magos (Adoration of the Magi / 1828 Sequeira), art

- Journey of the Magi (1846 Binder), art

Media in category "Black King (subject)"

This category contains only the following file.

- 1951 * Menotti (opera).jpg 251 × 352; 36 KB